From Morton Subotnick to Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, these 10 records have defined modular synthesis in their own unique and thrilling style

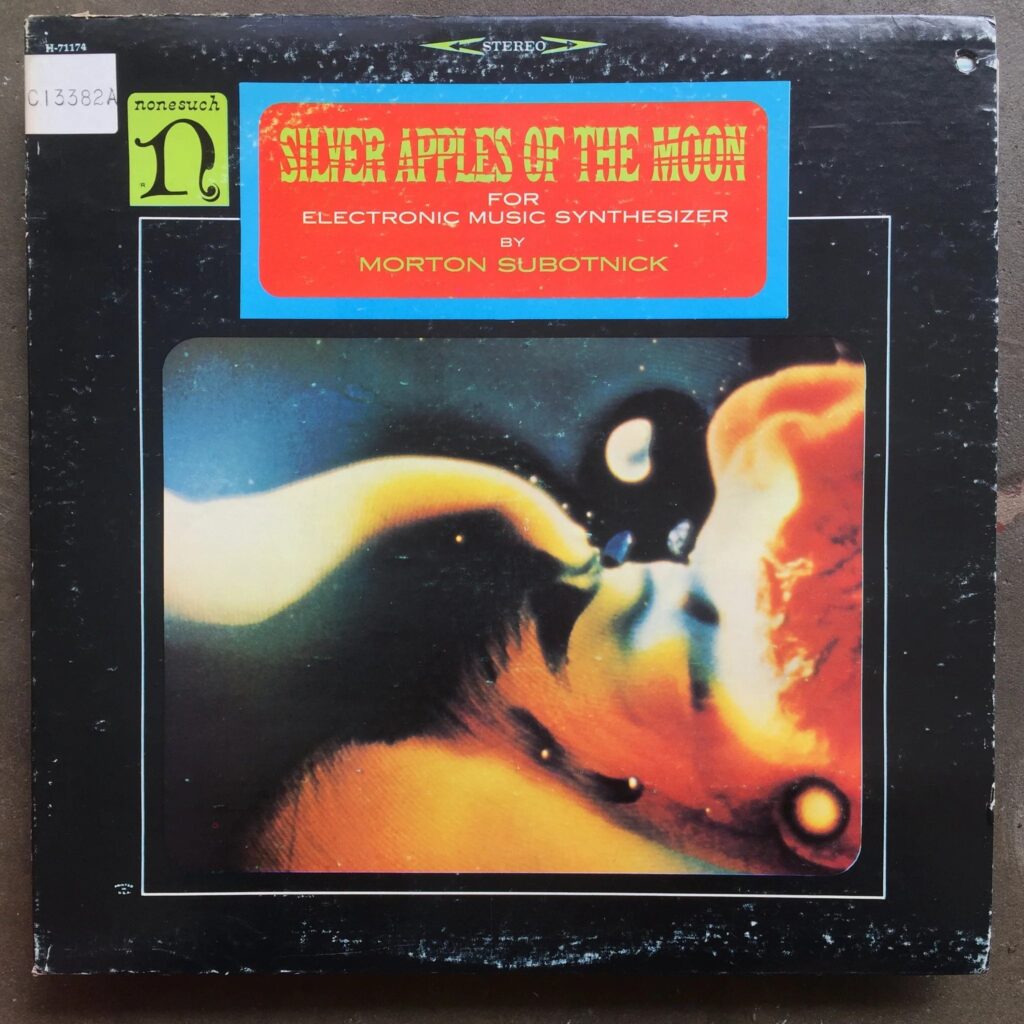

Morton Subotnick

‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’

(1967)

This may well be the first-ever synthesiser record. The title comes from the WB Yeats poem ‘The Song Of Wandering Aengus’ (which also gave those other American electronic outriders, Silver Apples, their name). While at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, which he founded with fellow composers Ramon Sender and Pauline Oliveros in 1962, Morton Subotnick commissioned engineer Don Buchla to make them a synth. The result was the Buchla 100. Subotnick started recording ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’ with it in 1966.

Side One is an academic riot of electronic sound, but Side Two gets really interesting as he presses the Buchla into producing punishing rhythms and manifold discordant interventions. You can hear pre-echoes of avant-synth work in there (think early Cabaret Voltaire and Devo), as well as the mind-melting racket of Aphex Twin.

When he played the piece in a New York nightclub shortly after its release in 1967, the audience danced. The strobe lights probably helped, but Subotnick was astonished by the reaction. Was this the birth of electronic dance music?

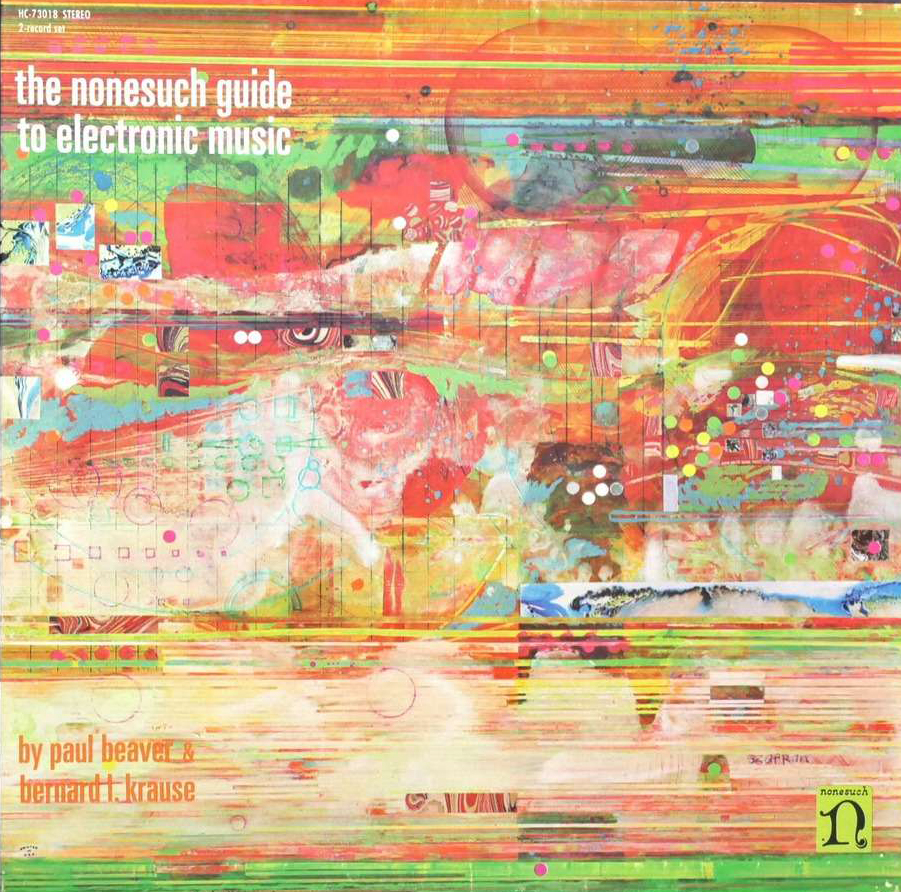

Beaver & Krause

‘The Nonesuch Guide To Electronic Music’

(1968)

Question: What could be better than a 1968 album designed to instruct listeners about the arcane new world of synthesisers, made by two OG high priests on the Moog modular? Answer: A double-LP boxset! With a 16-page booklet, dense with serious technical information about the Moog III and the emerging vocabulary around electronic music, this album actually charted in the USA.

Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause were session players and Moog evangelists, responsible for marketing Moog on the West Coast of America. The pair set up a tent at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 to show off the Moog III, and as a result, they and their Moog III were all over film soundtracks and rock royalty albums of the era, including George Harrison’s 1968 ‘Electronic Sound’ outing.

Alongside the NASA space programme, this album was a testament to America’s technological superiority. You really need to have ears of steel to listen to it, though, hence its proliferation in thrift shops for decades afterwards.

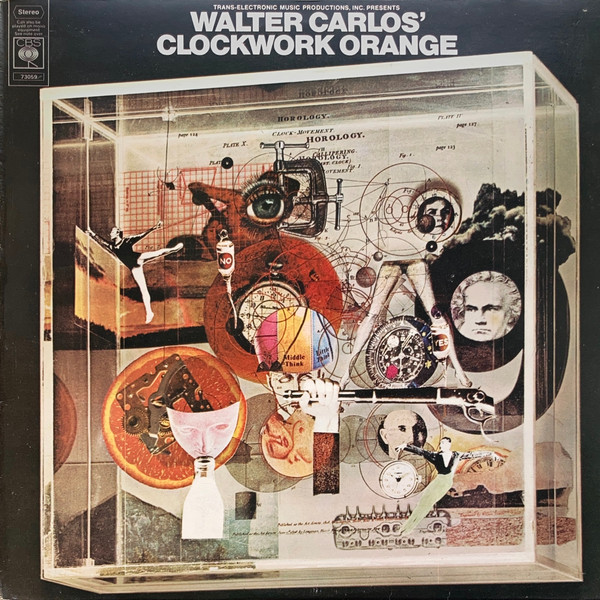

Wendy Carlos

‘Wendy Carlos’ Clockwork Orange’

(1972)

Here be the record! At the end of the 1960s, Wendy Carlos had made history with the ‘Switched-On Bach’ and ‘The Well-Tempered Synthesizer’ LPs, each a display of stunning technological and musical virtuosity. But the soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi boot boy movie by the first Moog modular expert has probably inspired as many Brit synth outfits as Kraftwerk.

The film’s transgressive teen horror show content and irresistible styling, combined with the haunting electronic music, was one hell of a viral load injected into the minds of British youth. There are a few versions, and Carlos’ copyright hawkery keeps them off streaming platforms.

The original soundtrack combined Carlos’ electronic pieces with orchestrated bits of Beethoven and Erika Eigen’s ‘I Want To Marry A Lighthouse Keeper’. Later in 1972, Carlos released an LP of just the electronic pieces, including the full 13-minute version of ‘Timesteps’, which had been reduced to just a few moments in the film itself and under five minutes on the soundtrack album. The 1998 CD issue is well worth tracking down for the added tracks ‘Orange Minuet’ and ‘Biblical Daydreams’.

Tangerine Dream

Phaedra

(1974)

This was the first Tangerine Dream record courtesy of the freshly inked deal with those groovy London hipsters at Virgin Records. In the tradition of classical composers before them, the Tangs (as the weekly music press dubbed them) turned to Greek mythology for inspo, and the story of a princess who fell in love with her stepson, thus appealing to a generation of public school headz with a classical education.

Musically, this is the foundation stone of the Berlin School, with the band’s recently acquired Moog modular and sequencer pushing the oscillators into hypnotising, warm basslines and some added delay to stress the soft bouncing. Edgar Froese’s Mellotron lines and the abstract sound design all came together to create a kind of music equally suitable for cathedrals as it was for your average dope-smoking Brit hippie’s bedsit.

The album’s smooth beauty belies the monstrous technical task of its recording, as the band struggled with the temperamental Moog’s tuning and many other limitations. It was worth it when the record hit Number 15 in the UK album charts, although it shifted a feeble 6,000 copies in Germany. Shame on you, Deutschland!

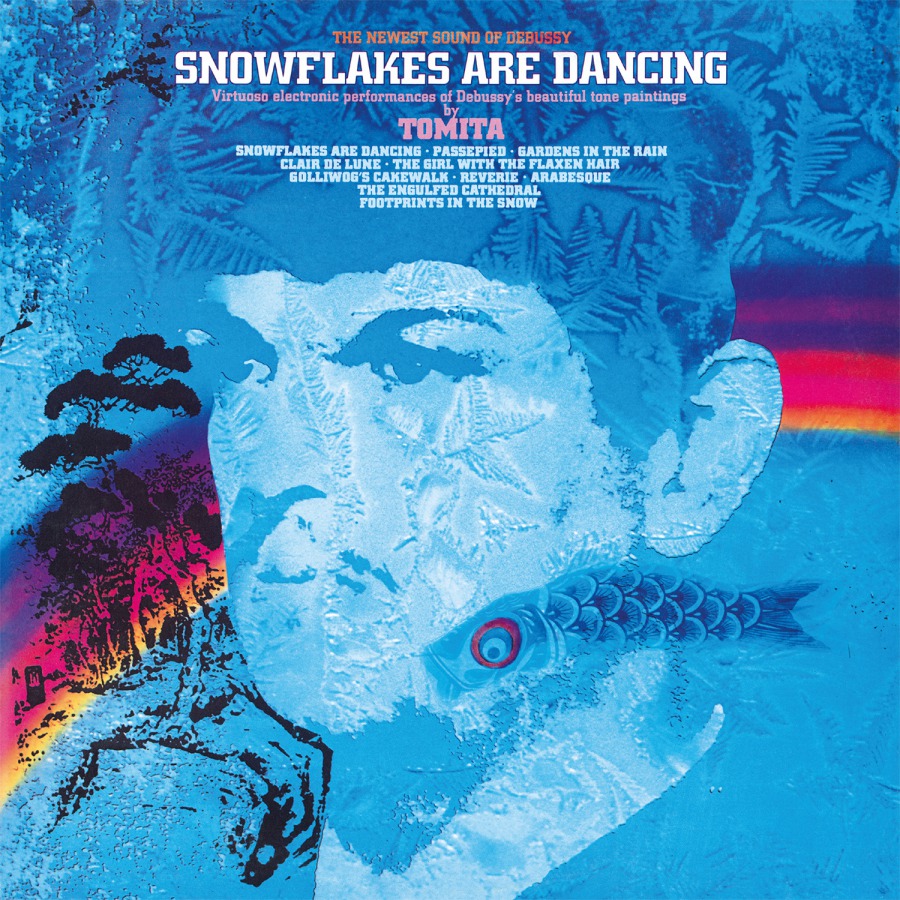

Tomita

‘Snowflakes Are Dancing’

(1974)

Meanwhile, in Japan, Isao Tomita was wrangling his modular gear for this reinterpretation of a selection of Debussy’s tone paintings. The result is a masterpiece. Tokyo-born Tomita was a composer with an extensive CV before he got his synth on. He’d been writing for television, theatre and film since graduating from Keio University in 1955. Wendy Carlos’ ‘Switched On’ records had opened his ears to the the new-fangled synthesiser, so he installed a Moog IIIP system in his studio and set about making his own huge contribution to the progress of electronic music.

His first synth album was released as ‘Switched On Hit & Rock’ in Japan in 1972, and retitled in the UK with typical cultural sensitivity as ‘Electric Samurai: Switched On Rock’. A collection of covers of Beatles, Elvis Presley and Simon & Garfunkel tunes, it’s both repellent and strangely brilliant. He and his studio team (including future YMO “fourth member” Hideki Matsutake) must have laughed their socks off when they laid down the synth emulation of Paul McCartney’s vocal on ‘Let It Be’.

His expansive interpretation of Debussy’s hits was pure joy, though, as was his 1976 intense synth rework of Holst’s ‘The Planets’.

Laurie Spiegel

‘The Expanding Universe’

(1980)

The sleeve notes give us the technical detail: “Composed in 1974-76 using a computer playing the actual sounds by controlling analog synthesis equipment using the GROOVE (Generating Realtime Operations On Voltage-controlled Equipment) hybrid system which was developed by Max Matthews and FR Moore at Bell Labs. Interaction with the computer was through a keyboard, a drawing tablet, push buttons and knobs, as well as complex ‘algorhythms’ written in FORTRAN.”

All of which must have read like alien space talk to the casual electronic music fan in 1980. Which is fitting, given that some of Laura Spiegel’s music from this era was shot into space on the ‘Sounds Of Earth’ gold record on Voyager in 1977. While the sleeve note detail is pretty jaw-dropping – computer software controlling synths, a drawing tablet, and algorithms in the mid-1970s – it fails to communicate the sense of freedom and unadorned beauty in the music she created with those tools from the future.

The synths – lab oscillators and modules kept in a studio 300 feet from the temperature-controlled room for the computer – chime and ring out with a delicate clarity as the patterns tumble around each other in a never-ending moebius loop of unrepeating repetition. Spiegel’s a guitar/banjo/lute player, which explains the staccato strumming of the synths on the impressive opening track, ‘Patchwork’. Her electronic pattern minimalism (which she called “slow change music”) on the expanded 2012 reissue is a twinkling, droning, ambient glory and includes the Voyager music.

Chris Carter

‘The Space Between’

(1980)

The Throbbing Gristle project still had another year to run before the cracks in the factory floor caused the collapse of the whole building. Chris Carter, as TG’s studious electronics guy, was working on his two recently acquired five-module racks of Roland System-100M gear, an EMS VCS 3 and a bunch of monophonic Korg and Roland synths. While his bandmates became the focus of some post-punk moral panic in the British tabloids, Carter was content to hunker down with his machines and noodle away to his heart’s content in the TG studio.

One of the results of his labours was ‘The Space Between’. Two sides of 15 untitled tracks, it was first released as a cassette on TG’s own Industrial Records. The tracks were finally given names when it was remastered for the CD reissue in 1991. Carter combines fleet machine rhythms with bright chords one moment, and skin-crawling drum machine work – reminiscent of John Carpenter’s ‘Assault On Precinct 13’ – with discordant drones the next, to unsettling effect.

In some ways, the album represents the end of the first modular era. The Roland modulars were miniature compared to the hulking great Moog systems. Widespread polyphony and MIDI were just around the corner, and pop music made with synths was about to dominate the UK charts. ‘The Space Between’ is a work that bridges two decades of synthesis – the dark and foreboding 1970s and the brighter, primary-coloured, poppy 1980s ahead.

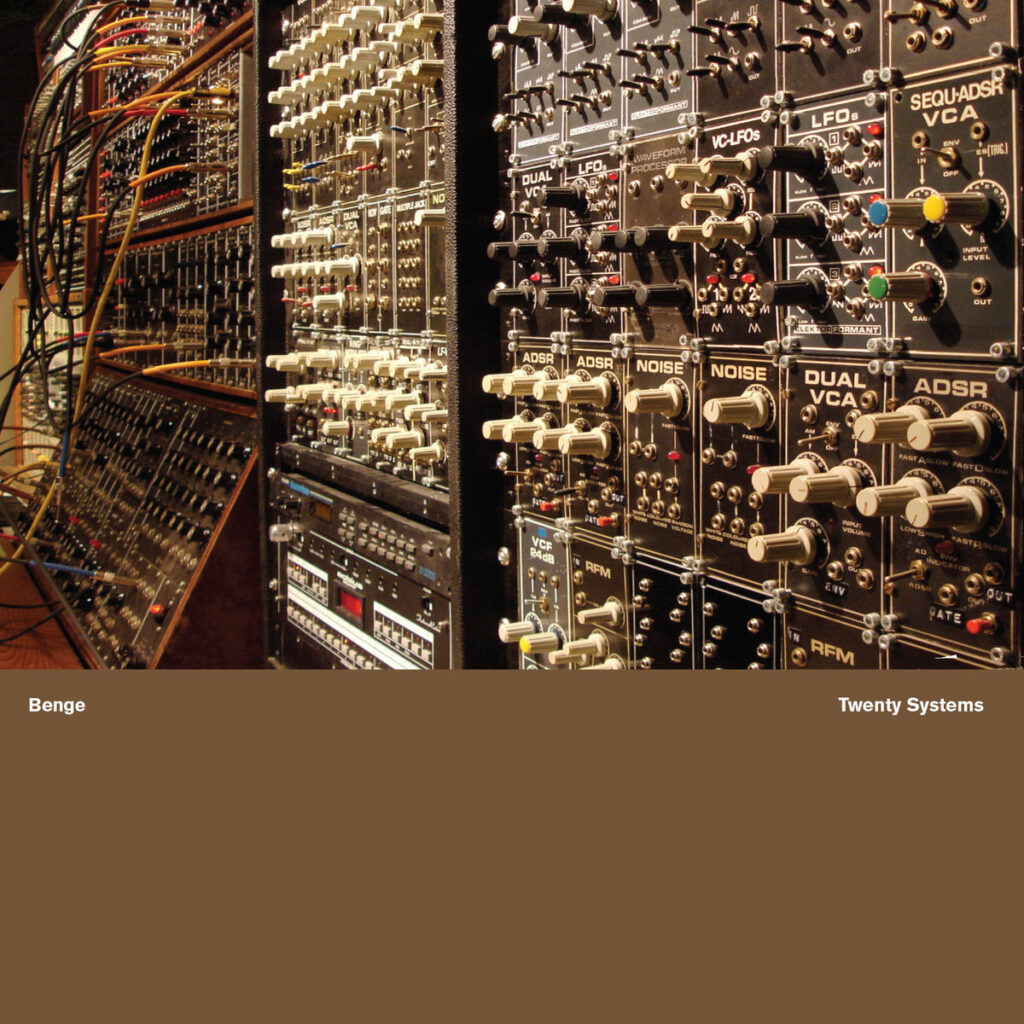

Benge

‘Twenty Systems’

(2007)

The 1980s saw modular systems being pulled out of studios and institutions. In every other skip lay a priceless modular mouldering away, destined for landfill. Like many of the records made with them, they were now deemed obsolete. Temperamental and cumbersome modulars were replaced with sleek polysynths and digital sampling systems. If you were smart, you could pick up unwanted gear for very little money well into the 90s.

One such canny shopper was Benjamin “Benge” Edwards. His first modular was a 1968 Moog system, and it was joined by the ARP 2500, a Serge Modular and a Roland System-100M, all of which are catalogued, along with other vintage synths, on this 2007 album with its 52-page booklet. “Twenty tracks, made on 20 synthesisers spanning 20 years,” it proclaimed. Brian Eno declared it “a brilliant contribution to the archaeology of electronic music…”.

The album serves as a historical document, emphasising the museum quality of some of the equipment. But it’s more than that. The message is that these machines were abandoned far too early, and Benge’s music shows there are still new and exciting sounds to be made with this old tech.

Suzanne Ciani

‘Buchla Concerts 1975’

(2016)

After a couple of pretty fallow decades for modular and its adherents, interest rocketed in the 21st century. The Eurorack system, developed by Doepfer in 1995, gained traction, and hundreds of boutique manufacturers sprang up in the 2000s.

A beneficiary of this renewed zeal was Suzanne Ciani. She’d been one of the West Coast electronic hippies who actually soldered circuit boards at the Buchla facility in the late 1960s. Her subtle and unique approach to the Buchla system was mostly only experienced in a live context, and even then only to small audiences of avant-garde enthusiasts.

While she made a decent living with commercial sound design for high-profile companies like Pepsi and Atari, tapes of her trailblazing Buchla performances were archived and forgotten. It was Andy Votel and his Finders Keepers label who brought these recordings to fresh ears 40 years after they were made. The two sides of Buchla improvisations capture the spirit of New York’s underground art scene of the mid-70s. As Votel put it: “The lost synth manifesto that could have changed the course of electronic music history by the first lady of modular synth history, Suzanne Ciani.”

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith

L’et’s Turn It Into Sound’

(2022)

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith’s 10th album is an example of how modular synthesis is now embraced in the workflow these days. Unlike her 2015 Buchla album ‘Euclid’ or the 2016 collaboration with her mentor, Suzanne Ciani, this is not a modular album per se, where the instrument itself takes centre stage. With ‘Let’s Turn It Into Sound’, modular synthesis is one of the tools that Smith used to create a dense and almost psychedelic experience.

The album’s title is a manifesto of sorts –a call to action shared by many electronic music makers and a reminder of the ethos the inventors and early practitioners of modular synthesis were pursuing. The idea was to develop a sound-making tool so versatile that creative people could use it to shape sonic environments that had never been heard before.

‘Let’s Turn It Into Sound’ certainly does that, mutating pop into an experimental playground of musical events to create a fantasia of sound – evidence that the modular wranglers of the current era are still exploring the outer reaches of what’s possible with electronic music.