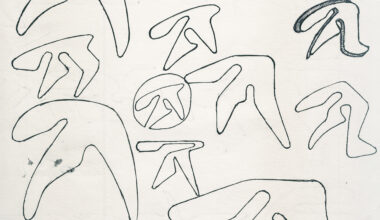

Morton Subotnick’s 1967 album ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’ is an experience of pure electronic music – or “new new music”, as Subotnick puts it. It was created solely on the Buchla, the modular synth he commissioned as an “easel” for creating the kind of studio art sounds he had in mind

Morton Subotnick was a teenage clarinet whizz in the early 1950s, and the youngest-ever member of the Denver Symphony Orchestra. There, he was taken under the wing of one of the orchestra’s violin players who inducted him into a world of art beyond the concert hall.

“He introduced me to what was going on in the avant-garde in Denver,” remembers Subotnick. “We had 48-hour parties for artists and scientists and various people when they would come through town, all in a painter’s studio, which was a huge factory building. The beat movement had started in Denver. I didn’t know that! I mean, I didn’t know what I was doing, I was just involved in these parties. We were just doing our thing.”

The painter was Angelo Di Benedetto, and in this beat-era, proto-Warhol scene of the early 1950s, Subotnick mixed with future stars of the avant-garde like filmmaker Stan Brakhage and composer James Tenney, who would go on to pioneer sampling experiments using Elvis Presley recordings and later worked with Max Mathews at Bell Labs developing computer music.

As a university student, Subotnick was exempt from the draft for the Korean War, but was eventually drafted anyway thanks to his patchy attendance. Fortunately for him, gifted musicians could avoid Korea and see out their service playing in military bands. Even better, he’d be stationed in San Francisco. The beat trail from Denver, where Jack Kerouac had sought out Neal Cassady in the late 1940s, also led to San Francisco.

“When I got to San Francisco, it had just been infected by Jack Kerouac,” says Subotnick. “So the world that I came into was one that I was really prepared for. That’s why I was first in terms of opening electronic music to what it would be. It wasn’t that I was so smart – it was just that I was carried with this wave.”

In San Francisco, he continued his studies with an MA at Mills College, where he met young composers Ramon Sender and Pauline Oliveros. Eventually, in 1961, the three of them set up what would become the San Francisco Tape Music Center. It was intended as an experimental studio facility where they could explore their ideas for new electronic music. Its first site, on Jones Street, was as much a flophouse for artistically inclined junkies as it was a studio. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it later burned to the ground.

Subotnick and Sender knew they needed a different electronic instrument that would allow them to create the new music they had in mind. And so they put an advert in a newspaper asking for engineers.

“Don Buchla was maybe the third person to answer the advert,” says Subotnick. “The first two were just high on drugs. He understood what I was talking about. He needed $500 for parts. I finally got the money together in the middle of 1964, so the Buchla would have been finished much earlier, but we did it all on paper first.”

In 1966, now equipped with a working Buchla, Subotnick moved to New York, where once again he landed in the epicentre of the avant-garde. In taking up a post as artist-in-residence at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University (NYU), and as musical director for the theatre at the city’s prestigious new Lincoln Center, he ended up with a studio on Bleecker Street near the Garrick Theatre.

The Garrick, aka the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theatre, was a 199-seat room above the Cafe Au Go Go, used by Warhol for premiering his films (it was only a few blocks from his studio, The Factory). Frank Zappa and The Mothers Of Invention played there every night for six months in 1967. The Cafe Au Go Go hosted hundreds of bands throughout the 1960s, none of which meant much to Subotnick, a family man with two young sons, beavering away with his Buchla. But various musicians did wander into Subotnick’s studio to sit in on his late-night sessions.

“They sat around, probably doped up,” recalls Subotnick. “We didn’t have locks on the doors. I didn’t mind. One night this guy comes in, and he was dressed like everybody else except his pants were pleated, which made him look like a phoney to me. He said he was the head of this new record company, and they’d like to offer me $500 to make a record. I thought he was making fun of me, so I kicked him out.”

The next day, realising the fake hippy was none other than Jac Holzman, head of record labels Elektra and Nonesuch, Subotnick tried and failed to contact him. He returned to his studio in the evening, convinced he’d blown a golden opportunity.

“I’m in the studio around the same time and he comes in again,” remembers Subotnick. “I’m ready to go down on my knees and say, ‘I’ll do it for nothing!’. He holds his hands up and says, ‘Don’t come near me! Just listen to what I have to say. We’ve talked about it a lot. We’ll offer you $1,000.”

It took Subotnick over a year to complete the recordings which became ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’, but he wasn’t sure how it would be received.

“When I got the thing done, I thought, ‘Who’s gonna listen to it?’.”

It turned out a lot of people would listen to his otherworldly soundscapes. The first electronic album specifically commissioned for a classical label (Nonesuch), it was released in July 1967 and became an unlikely hit, setting the avant-garde alight. Subotnick’s place in music history as a visionary of electronic music was sealed.

Now aged 90, he remains as vigorously engaged in his work as ever. Computers finally became fast enough to “take my studio to the audience” to perform live synthesis.

“I can actually do what I intended to do way back in 1962!” he exclaims.

He’s booked to perform at the opening of the Venice Biennale in October with the new piece he’s been touring, titled ‘As I Live And Breathe’.

I mention an interview Subotnick gave around his 80th birthday, when he said he might start thinking about “maybe retiring a bit…”.

“Retire from what?” he says. “You know, when you retire you’re supposed to get into your hobbies. But what if your hobby is living?”