Dada, Hugo Ball’s quirky anti-art movement that inspired bands galore, celebrates its centenary this year. From 1916 and Zürich’s Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 to 2016 and the return of Yello, we squint at the cogs inside this cuckoo Swiss concept

‘In Italy for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”

Orson Welles as Harry Lime in the 1949 film ‘The Third Man’ wasn’t to know that Yello would later appear over the mountainous Swiss horizon of the 20th century. But his airbrushing from Switzerland’s history the contribution to European culture made by one Hugo Ball and his Dada movement of a hundred years ago is less forgivable.

Dada, short-lived as it was in its original incarnation, endures as an influence in pop music, where it infiltrated both the mainstream, allowing Yello and the Pet Shop Boys to carve out territory, to the avant-garde underground of Cromagnon and The Residents, and in-betweeners like Devo. One of Dada’s architects, Tristran Tzara, came up with the cut-up technique for creating poems from newspaper and magazine text, later used by both William Burroughs and David Bowie.

Dadaist ideas and are so entwined in some of pop music’s most interesting chapters, it’s difficult to separate the threads. Even if some of these bands have never heard of Hugo Ball, they’re influenced by Dada whether they like it or not. Today, strong traces of Dada might be found in the high def videos and live spectacles of Lady Gaga and Miley Cyrus, and in Japan with the synchronised salary man absurdist pop band World Order. Dada was strong in Japan; the 1960s Japanese TV show Ultraman featured a monster called Dada, who was invited to meet the Swiss ambassador earlier this year on the 100th anniversary of Dada. If that’s not Dada, nothing is.

Hugo Ball was an artist and a poet, a German citizen who had fled to neutral Switzerland during the First World War to avoid being forced to take part in it. He opposed the war, calling it a “glaring mistake”, and his revulsion at the bloodshed was sublimated into his Dada Manifesto of 1916. Hugo and his hip artist pals cooked up Dada at a time when art movements with manifestos were all the rage. It came hard on the heels of Futurism and while there is some crossover with the conceptual nature of the two movements, Dada has the huge historical advantage of not being keen on either fascism or war. Futurism also had “scorn for women” written into it, whereas one of Dada’s main movers was Sophie Taeuber-Arp, a performer who went on to create some the best known textiles pieces of the era.

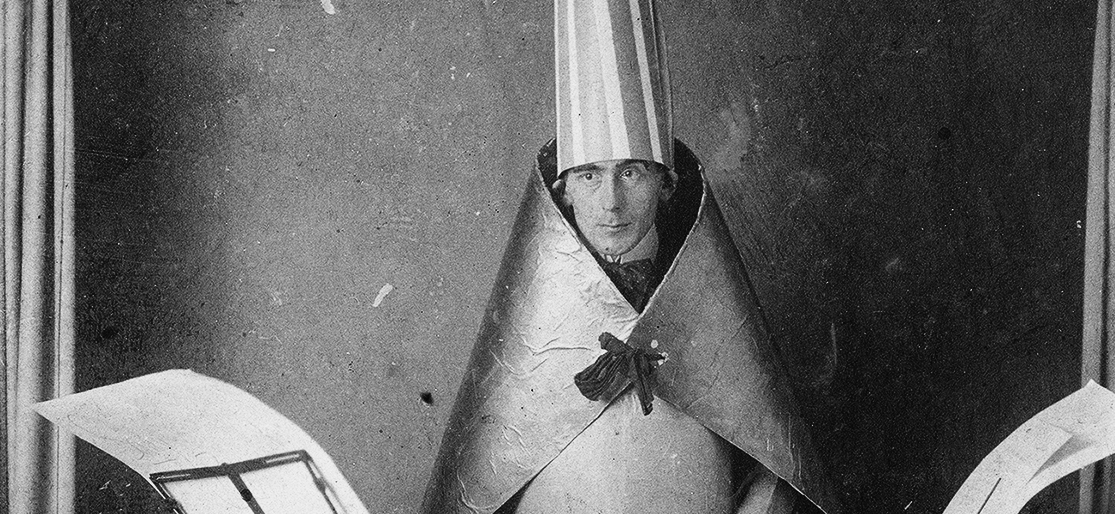

“All living art will be irrational, primitive, and complex; it will speak a secret language and leave behind documents not of edification, but of paradox,” Ball said. And to prove the point, he wrote the Dadaist poem, ‘Gadji beri bimba’ and performed it, dressed as a weird lobster/robot thing with reflective blue cylinders for legs and a cardboard cape, at the club he founded in Zurich, Cabaret Voltaire.

The poem later earned him a co-writing credit on the Talking Heads track ‘I, Zimbra’ on 1979’s ‘Fear Of Music’, not that there was any risk of Byrne and co. having to pay out royalties; Hugo Ball died of stomach cancer in 1927, aged just 41. One of many Dadaist sound poems, or verse ohne Worte (poems without words), ‘Gadji beri bimba’ is a series of sounds, rather than language, purposefully devoid of meaning, but delivered with passion. The event took on spiritual and even religious overtones, with Ball saying that he found his voice taking on the intonation and delivery of a high priest. At the end of his performance, the lights went out, and Ball was carried off the stage “trembling like a magical bishop” according to eyewitness accounts.

Viewed in that context, the costume he wore becomes a parody of the garments of religiosity, a kind of uniform, and it’s not a huge leap to imagine the parody stretching to military uniform that so many young men went to their deaths wearing in the four years of the First World War. Dressing up is, and should be ridiculous, Dadaism seemed to be saying, and they took every opportunity to do so.

“How does one become famous?” asked the Dada manifesto. “By saying dada,” it answered. It ends one section with the immortal lines, “dada m’dada, dada m’dada dada mhm, dada dere dada, dada Hue, dada Tza.”

Under this apparent nonsense was a very real and visceral reaction to the horrors of the First World War that was engulfing Europe at the time. The desire to shock and confound went hand-in-hand with the idea that the irrational had become the norm, that slaughter on an industrial scale was somehow a reasonable outcome of human interaction. If that was the kind of world we live in, then what was needed was a purging, some kind of mantra which would cure all ills… as long as you dressed in your favourite robot/lobster outfit.

Dada was a multi-discipline movement, incorporating collage, painting, photography, poetry, performance, design and fashion, and it was as much about the artist’s behaviour as the work they made. Any self-respecting band will be immersed in all of these aspects of their output. It inspired Situationism, which informed some of the intellectual energy driving punk and what came after it. Dada is the blueprint. Dada is the primal soup from which so much interesting music emerged.

Dada is, perhaps, what you get when artists are pushed into a corner by an insane society and can only defend themselves and their humanity by responding with an entertaining but scarily unhinged outpouring of psychedelic gibberish. Dada set out to freak people the fuck out, while making them laugh. When people start asking if an artist is serious or taking the piss, Dada is lurking in the shadows, and it’s that impulse to embody paradox and weirdness that lives on in Dada influence in music. Dada. Dada m’dada, dada m’dada dada mhm, dada dere dada, dada Hue, dada Tza.

The Dada Effect

Inspiring artists and shaping record collections for 100 years, we pick out 30 acts Riddled with anti-art mischief

The Residents

Steeped in mystery (largely solved in the pages of Reddit via voice recognition software and other next-level sleuthing) The Residents are best known for their eyeball headgear and Dadaist moves like recording themselves jamming along to well-known tunes and then stripping the original tunes out and releasing the results on an album they called ‘The Third Reich ’n’ Roll’.

Devo

Named in part to sound like an art movement, Devo’s wackiness was a trojan horse for their deeply held revulsion at the stupidity of their fellow apes, with a manifesto that outlined their theory of de-evolution. Hugo Ball would have approved of the multifarious costumes and masks, many of which were available to purchase via album inner sleeves which doubled as order forms in a cake-and-eat-it satire of American consumerism.

Sigue Sigue Sputnik

Roughly shagging the 80s with an exploding day-glo love missile of hair, runaway drum machines and breakneck synths, with Moroder producing.

Renaldo & The Loaf

An architect and a pathologist who made acoustic instruments sound like synths thanks to mucho tape loops, muffling and detuning.

The Screamers

Mystifyingly, Los Angeles’ The Screamers remained unsigned for their lifespan (1975-81) and therefore released no product. No guitars, instead two keyboard/synth players and the jerking intense persona of singer Tomata Du Plenty allowed them to deliver an apparently awesome live experience of electro punk performance art that electrified audiences. They held out to make a video album, and early visual experiments of it lurk about on YouTube which certainly give us a good feel for their confrontational strangeness.

Space

French synth leftfielders pre-dated Daft Punk by a good 15 years with their space helmets and synthesised disco beats in 1977.

Laibach

The musical wing of political Slovenian art collective, their visual style and sonic deconstructions appropriated much from Dada. Made a hell of a racket.

The Tubes

The Tubes piled props, characters, sex, drugs and explosive technological flash into their live shows, creating an extravaganza that teetered between burlesque and insightful critique of contemporary society. The Tubes’ thrilling and absurdist live show was recorded in the great double live set ‘What Do You Want From Live’, recorded in London, capturing them at something of a career high.

The KLF

Among the The KLF’s better known public (anti-)art interventions is the collaboration with Extreme Noise Terror at the BRITS in 1992, which ended with Bill Drummond spraying the audience with pretend bullets from a machine gun in scenes reminiscent (and probably inspired by) the climax of the film ‘If…’ . They also burned a million quid (or did they really, etc), and performed with huge horns protruding from the cowls of their monk habits.

The Flying Lizards

Made cover versions interesting in the early 80s with quirky takes on standards. Their deadpan version of ‘Sex Machine’ is a treat.

Tik and Tok

Two guys pretending to be robots parlayed a pretty handy career out of being Tik And Tok in the early 80s, becoming the house automata for the early 80s electronic/new romantic music scene.

Klaus Nomi

Klaus Nomi’s strangeness has the power to startle more than 30 years after his death. The three sticks of hair spiked heavenwards, the plastic suit, the black bee sting lips and the voice… Nomi was a countertenor, which means he was able to suddenly unleash a voice so eerily beautiful and at odds with the synth pop he generally purveyed that humans would stare at him with their mouths open. Pals included fellow travellers of the strange, David Bowie and Man Parrish.

Cromagnon

They made one album in 1969 which was so monumentally strange that it still ranks as one of the oddest ever made. The story was that the album’s architects Austin Grasmere and Brian Elliot sought out a demented hippy tribe to provide the shouting and primal beats (made with bones and stones, apparently), and that future members of both The Residents and Negativland were in that tribe. Not true, it turned out, but the album is a ferocious noise-fest which incorporates tape music and wild group improv and includes bagpipes.

Butthole Surfers /Jackofficers

Because obviously the Butthole Surfers weren’t challenging enough, Gibby Haynes and Jeff Pinkus had to make an album of sample collage (‘Digital Dump’). Live shows involved them doing little more than pressing the play button on their Sony Walkman.

Nash The Slash

A Canadian violin player bandaged à la ‘The Invisible Man’ won Numan’s patronage and a release on The Residents’ Ralph Records. He once claimed his real name was ‘Nashville Thebodiah Slasher’ and in 2008 released an album called ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Nash’. Nash died of a heart attack in 2014.

Sparks

The cool dude singing, the odd-bod playing keyboards, chart success beckons. Tacky tigers?

Kraftwerk

Forty-odd years of German inscrutability on an industrial scale has led to Lycra ‘Tron’ suits on late-middle aged men. Kraftwerk are the masters of odd.

Björk

She wore a dress that looked like a swan for the 2001 Academy Awards. And laid a big swan egg on the red carpet.

The Art Of Noise

The partnership of studio genius Trevor Horn, business brain Jill Sinclair and clever music journo Paul Morley birthed the ZTT label in 1983. The label was named after the Futurist poem of the same name, and the label’s Dadaist/Futurist/Situationist thievery was mostly poured into the Art Of Noise, a suitably anonymous studio project which needed some conceptual cladding for it to make any sense, which it still failed to do, but that didn’t stop them selling bucket loads of records and being very odd indeed.

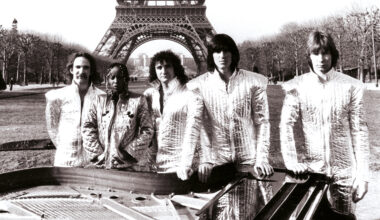

Rockets

France’s Rockets flew the flag for weird in the 70s, never more so than when covering Canned Heat’s ‘On The Road Again’ with a vocoder and synths, dressed in their trademark sci-fi outfits with their bald heads painted silver.

Aphex Twin

Quiet country boy he might have been, but the unsettling videos that went with the bananas tunery sure made up for it. His obsession with grafting his own head onto other people just scratches the surface of his visual freakery.

Fad Gadget

Frank Tovey (for it is he) was the first artist Daniel Miller signed to Mute in 1979. Tovey didn’t think of himself as a musician, and used kitchen implements, drills, razors and anything else to hand to create music in his studio, which was a cupboard under the stairs, eventually adding a drum machine and synthesiser. Live shows included Tovey tarring and feathering himself, songs about depilation (‘Lady Shave’) and a backing band dressed as bakers. Tovey, who had always suffered from heart problems, died of a heart attack in 2002, aged 45.

Yacht

Arch post-modernist anti-art in the form of sleek synthpop from L.A. couple with their own manifesto. In what turned out to be a complicated and ‘problematic’ hoax, they got caught out leaking a sex tape… of themselves.

The Plastics

Angular ultra-Devo influenced spiky synth/new wave/stylish art pop from Japan circa 1980 with heavy pals like David Byrne and The B-52s.

Frank Chickens

From Edinburgh Festival comedy cabaret (1984) to a hit single (‘We Are Ninja’) to the anti-TV TV show ‘Kazuko’s Karaoke Club’, Frank Chickens might lean a bit heavily on the ‘wacky Japan’ cliché, but they’re a 30-year performance art project.

Revolting Cocks

RevCo were the transgressive industrial supergroup, lacing their gigs with nudity, scary masks and cowboy hats, Euro-redneck confrontation style.

Finitribe

Sonic extremists whose early live shows were battlegrounds of blood and mayhem gradually honed into merely bonkers. Dressed up a Hoovers once.

Altern-8

Wore facemasks so people didn’t twig they were the same group who played last week under a different name.

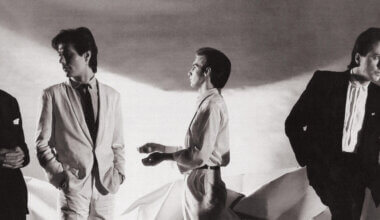

Pet Shop Boys

Pilfered liberally from Dada with their own must-have fashion accessories. Namely big pointy hats just like Hugo Ball in 1916.

Die Antwoord

The spirit of Dada lives on in South Africa’s Die Antwoord whose commitment to their schtick is unwavering. Are they hip hop? Are they rave? Are they serious? Really? They take inspiration from a South African style known as zef, which makes an art form out of the naff, and say they use their art “as a shock machine to wake [people] up”. Everything they do is challenging in all kinds of unexpected and often quite horrible ways.