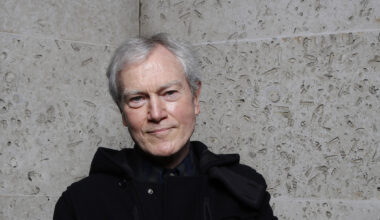

Beautify Junkyards bring a Portuguese perspective to Ghost Box’s retro-futurist aesthetic. Frontman João Branco Kyron discusses Portugal’s 1974 military uprising, his love of British acid folk, and disturbing spectral voice recordings

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here