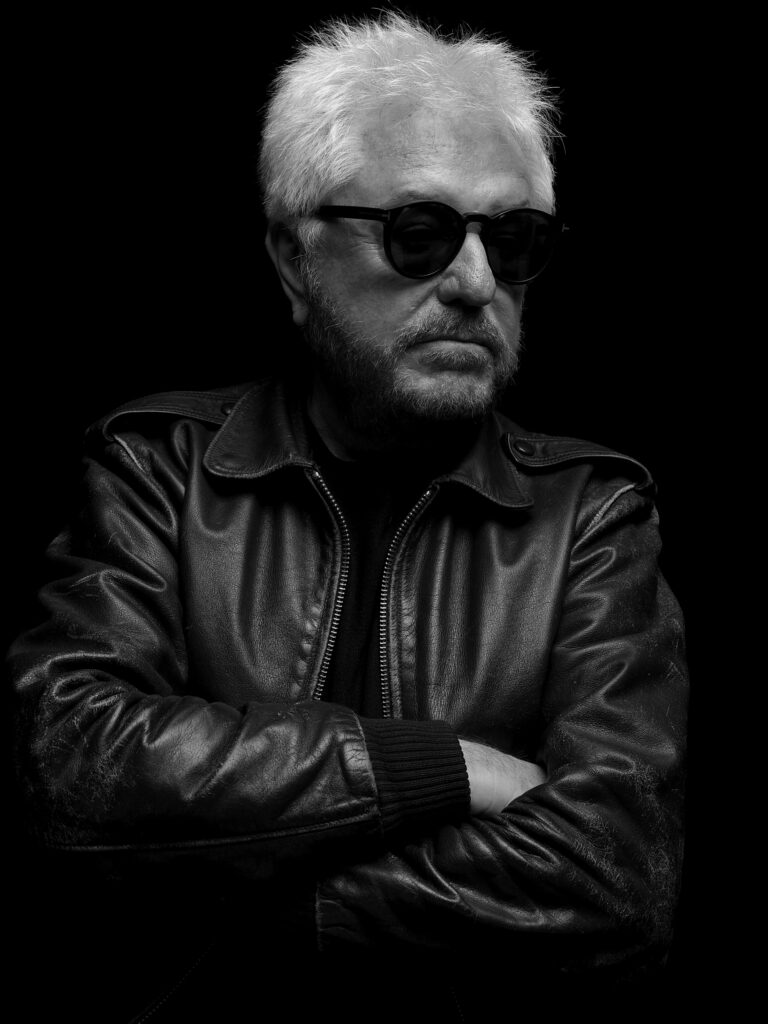

The French disco don returns with a new album that both stretches back to his dancefloor beginnings and reaches into the future. Cerrone talks sampling, Soho and Studio 54…

Discotheque might be a French word, but it wasn’t truly imbued with Frenchness until Marc Cerrone arrived on the scene. While the Americans might have invented disco, Cerrone took it up a notch in 1976 with the vertiginous 16-minute dancefloor epic ‘Love In C Minor’. Like Jean-Luc Godard or Serge Gainsbourg, the Frenchman borrowed something zeitgeisty from across the Atlantic and gave it a unique twist français.

The following year, his electro-based ‘Cerrone 3 – Supernature’ album, recorded at Trident Studios in Soho, London, would go on to sell more than eight million copies worldwide and become one of the cornerstones of filter disco and French touch. His influence still permeates dance culture, even if his name is less known to contemporary audiences than those of Giorgio Moroder and his old friend Nile Rodgers.

In 2020, le père du disco is back to reclaim his throne with a new album, ‘DNA’. If the artists he influenced seem reluctant to pay overt homage to him, then this record is a nod to his own glorious past and in particular to ‘Supernature’, which will always sound like the future, the unsung hero of 1977’s electro trinity alongside ‘I Feel Love’ and ‘Trans-Europe Express’.

And yet ‘DNA’ is not an exercise in nostalgia, there are plenty of reference points aside from himself – from Pink Floyd on the title track to ‘Computer Love’-era Kraftwerk on ‘I’ve Got A Rocket’, with some ‘Tubular Bells’ (’Close To The Sky’) and mid-90s progressive house à la Robert Miles (’Air Dreaming’) thrown in for good measure.

It’s an assured record, surprisingly brimming with freshness for a 26th studio album.

“It’s my new baby and I can’t wait for it to come out!” says Cerrone enthusiastically, over the phone. Our interview is conducted by telephone in English, and via email in French, in an attempt to overcome the language barrier. As we try to converse in a kind of mid-channel franglais, Cerrone says, “Ahh, your French is like my bad English”. At one point, when he completely misunderstands one of my questions, he puts his engineer Richard Turek on the line, and instructs him to talk me through the equipment used on the new record. It’s a misunderstanding that turns out to be fairly fascinating in a nerdy kind of way.

Although Cerrone embraced the cybernated world, taking the trouble to digitise his entire back catalogue when the technology became available, on ‘DNA’ he has returned to much of the analogue equipment he would have utilised in the late 70s, creating a cyborgian mix of modern and classic, from digital workstations to modular plug-ins.

“We used the Prophet-5, the ARP 2600 and a Minimoog,” says his engineer, dutifully, “as well as a very nice keyboard that came out recently called the Korg Prologue. Of course, Marc uses a Roland drum machine, but we avoid quantising as much as possible because it kills the groove.”

The similarities between ‘DNA’ and ‘Supernature’ aren’t just about the hardware, they’re thematic too.

“After composing ‘The Impact’ for the new record,” says Cerrone, returning to the phone, “I suddenly realised that I’d found myself back in the same orbit as ‘Supernature’. In creating this bridge, it then occurred to me that a sample would be perfect.”

Cerrone searched for a credible authority on climate change, and via Google, stumbled upon a conference speech by the renowned anthropologist Dr Jane Goodall, who gave her blessing for it to be used as soon as he contacted her. It’s a sobering message about the state of the planet from an artist who, by his own admission, usually loves to play the clown.

‘Supernature’, by comparison, is a Wellsian sci-fi fantasy with lyrics written by new wave icon Lene Lovich. Cerrone initially approached her in Piccadilly Circus as she busked, dressed head-to-toe in purple.

“And the sax she was playing was plastic,” he adds. “Seeing me laugh, she came over, and I invited her to Trident Studios, where I was recording my second album, ‘Cerrone’s Paradise’. There was this symbiosis between us, so I suggested she write the lyrics for my next album with the basic direction: sexy et osée [sexy and daring] as we say in France.”

Cerrone and Lovich had long conversations about the planet and about ‘The Island Of Dr Moreau’, and so the song they wrote ended up becoming a conflation of the two.

“She brilliantly summed up the message that we wanted to convey,” he says. “Although I am obviously concerned about the treatment of the planet by humans, as many people are, ‘DNA’ is also an album that plunges me back to my electronic years with vintage sounds and atmospheres.”

There’s nudity on the cover of the new record, of course there is. It’s something Cerrone is famous for, but this time it’s only an artist’s impression of two Greek statues bookending the universe. It’s a far cry from the eurotrash eroticism that got him into trouble with the Mouvement de libération des femmes back in the 70s and 80s, with images like the one he chose to use on the cover of ‘Cerrone’s Paradise’ where he’s crouched down as a naked woman is sprawled across the top of his fridge.

“Oh, they just denounced me for using images of women, but I replied each time, ‘No, my songs are sung by women, so it seems logical to put them on the covers’,” he says, somewhat unconvincingly.

Cerrone admits to a longing for the days of the great provocateurs, commenting that what worked well in the 70s wouldn’t be acceptable today.

Uncharacteristically devoid of raunchiness, the album sleeve for ‘Supernature’ was dystopian, depicting Cerrone standing in front of a surgical bed with characters in lab coats and animal masks lying prostrate on the floor. It’s an image that’s hard to forget and one that I’ve often thought about, and I finally get to ask… pourquoi?

“It was one of the very first records that talked about our civilisation impacting the planet, so I did the sleeve like that because I was trying to explain that if we continued to behave like animals then we would eventually end up as animals.”

So there you have it.

In 1977, a big year for Cerrone, he fell foul of the media at home after he bought a chateau in the Yvelines region, next door to Versailles, for his young family. He called in builders to do some work, who subsequently destroyed the historic building while carrying out renovations. It became a major story in France and he was pilloried in the press as a gauche and tasteless vandal, a scandal that was largely unfair. He missed much of the controversy though, as he was spending most of his time in America doing promotional work.

“Ah, so you’ve read my biography,” says Cerrone, suspiciously. “It’s of no interest, really, it’s just the hustle and bustle of life. I barely remember!”

Cerrone’s biography, for the record, is a rags-to-riches story, with the ostentatious playboy superstar coming from humble beginnings in the Parisian banlieues of Vitry-sur-Seine, the son of Italian immigrants. He was born in 1952 under the shadow of towering social housing, with the nearby brutalist Choux de Créteil unveiled to the public in 1974, just as his first band Kongas began to get their freak on. I tell Cerrone that I once took the metro up to Créteil to visit the spectacular, vegetable-like cylindrical buildings designed by Gérard Grandval.

“So, we do not like the same things!” he retorts, laughing.

According to the biography ‘Cerrone: Et Pourquoi Pas La Lune!’ (‘And Why Not The Moon!’), Cerrone’s parents divorced when he was five and his mother subsequently fell into a deep depression. By order of the courts, instigated by his father, he and his siblings were taken into an orphanage run by nuns in Auteuil for a short period, a time that must have caused distress, and apparently put him off organised religion for good. His early life was tough, but things improved somewhat when back in the arms of his mother. She bought him a drum kit.

“She made me fall in love with music, and helped me to avoid going wrong somewhere,” he says. “It’s as if she introduced me to my best and most faithful friend who I share everything with. The love I received from my parents and my modest upbringing instilled in me a real sense of value and balance, I think. Throughout my life I’ve tried not to magnify the good things or give in to the bad times, either. It’s certainly an attitude I’ve tried to pass onto my children.”

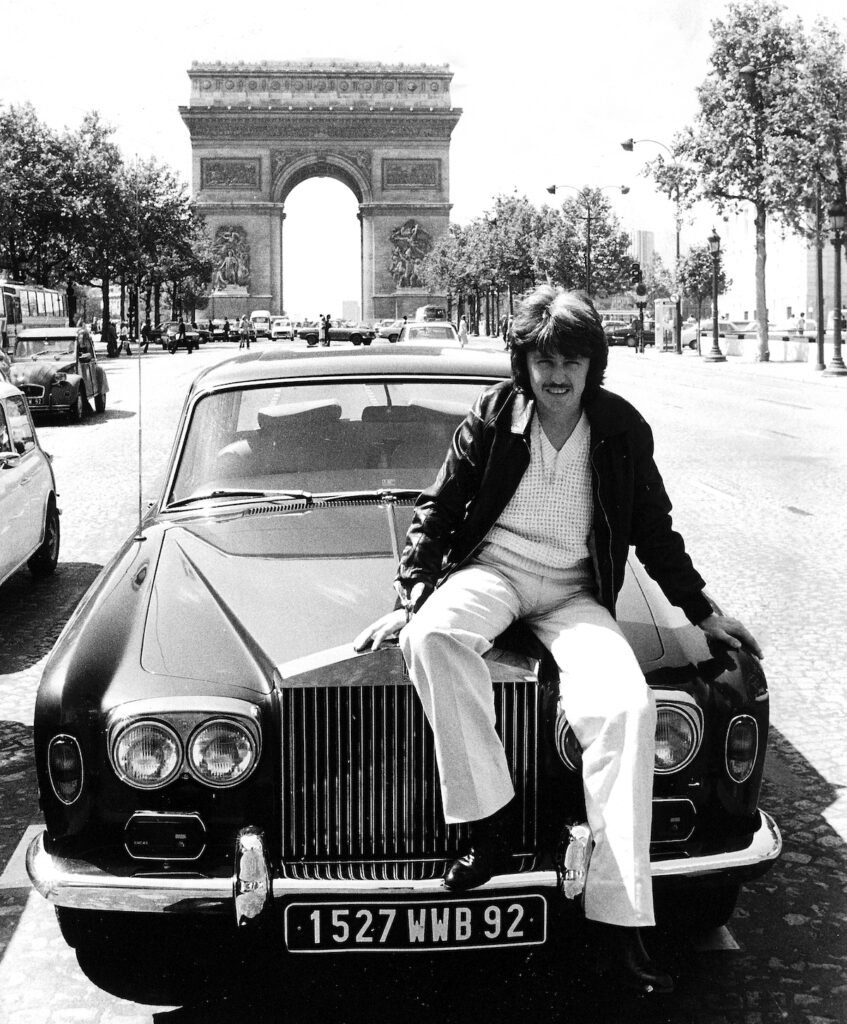

When Cerrone made a fortune with his early records, he drove around to see his father in a new Rolls Royce. A moment of triumph that turned into one of embarrassment.

“Yeah, at the time, having a nice car was a sign of success, so like any self-respecting badger, I went there to show off. I remember he said to me, ‘Park it away from the house, I don’t want the neighbours to see it’. That was out of modesty and it was a part of my education.”

Cerrone’s big break came in 1976 thanks to a slice of outrageous good fortune. A box of 300 ‘Love In C Minor’ white labels, recorded for his own Malligator imprint, was mailed to the US by mistake, instead of some Barry White albums. The records were quickly disseminated and found their way into clubs, and a search to find the artist behind the mysterious banger was launched.

When Cerrone (6,000km away, and oblivious to what was happening) wasn’t forthcoming, Frankie Crocker & The Heart And Soul Orchestra covered the song with a degree of success. It was then that it came to Cerrone’s attention, and he was flown to New York where he did a deal with Atlantic Records. Before he knew it, his song was headed for the top of the charts, he was a star in America and he would soon appear on Dick Clark’s ‘American Bandstand’, an invitation he still sounds surprised about.

“That was my first TV!” he barks. “Atlantic didn’t tell me I was going to be on the show. They just said, ‘Stand at the back and maybe Dick will hold up the cover and speak a little bit about your record’, which I was happy about. And then I heard the beginning of my track and I looked at the guy from Atlantic and said, ‘What’s going on?’. He said, ‘Marc, it’s you! Let’s go!’. So Atlantic Records had arranged for the bass player, the keyboard player, the backing singers and everybody to be there, and in the middle was a drum kit. And Dick Clark said, ‘Marc, they’re your drums, let’s go!’. It was totally live so can you imagine my surprise. You can see it now on YouTube. Just look at my face! I was like a bébé.”

Did he feel resentful at all that the Americans embraced him while the French failed to raise any enthusiasm at first?

“All the French majors had told me, ‘The title’s too long’, ‘the drums are too far forward’, ‘there’s far too much sex’! So I wasn’t surprised. ‘Love In C Minor’ is 15 minutes long, and the drums are at the front. It was logical because I’m a drummer, but I was pretty sure we weren’t going to sell more than 20 copies.”

Instead, things began to get crazy. He became a household name in the biggest market in the world, had a video directed by Monty Python (‘Take Me’), and artists such as Led Zeppelin guitar-god Jimmy Page would drop by his studio in Soho to collaborate.

“Jimmy’s a really friendly guy and he accepted my invitation to play on ‘Rocket In The Pocket’,” says Cerrone picking up the story. “I was so fond of him and I got to realise an incredible dream.”

I wonder what it was like recording in the heart of Soho at that specific time in history.

“Très cul!” cries Cerrone.

Very ass?

“Yes, very ass!” he exclaims. “It’s a French expression that means ‘hard sex’. It’s tres cul. There were sex shops all around, bars everywhere and prostitutes galore. It was the really hot place in London, so I prefer not to tell you in detail about our studio sessions.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

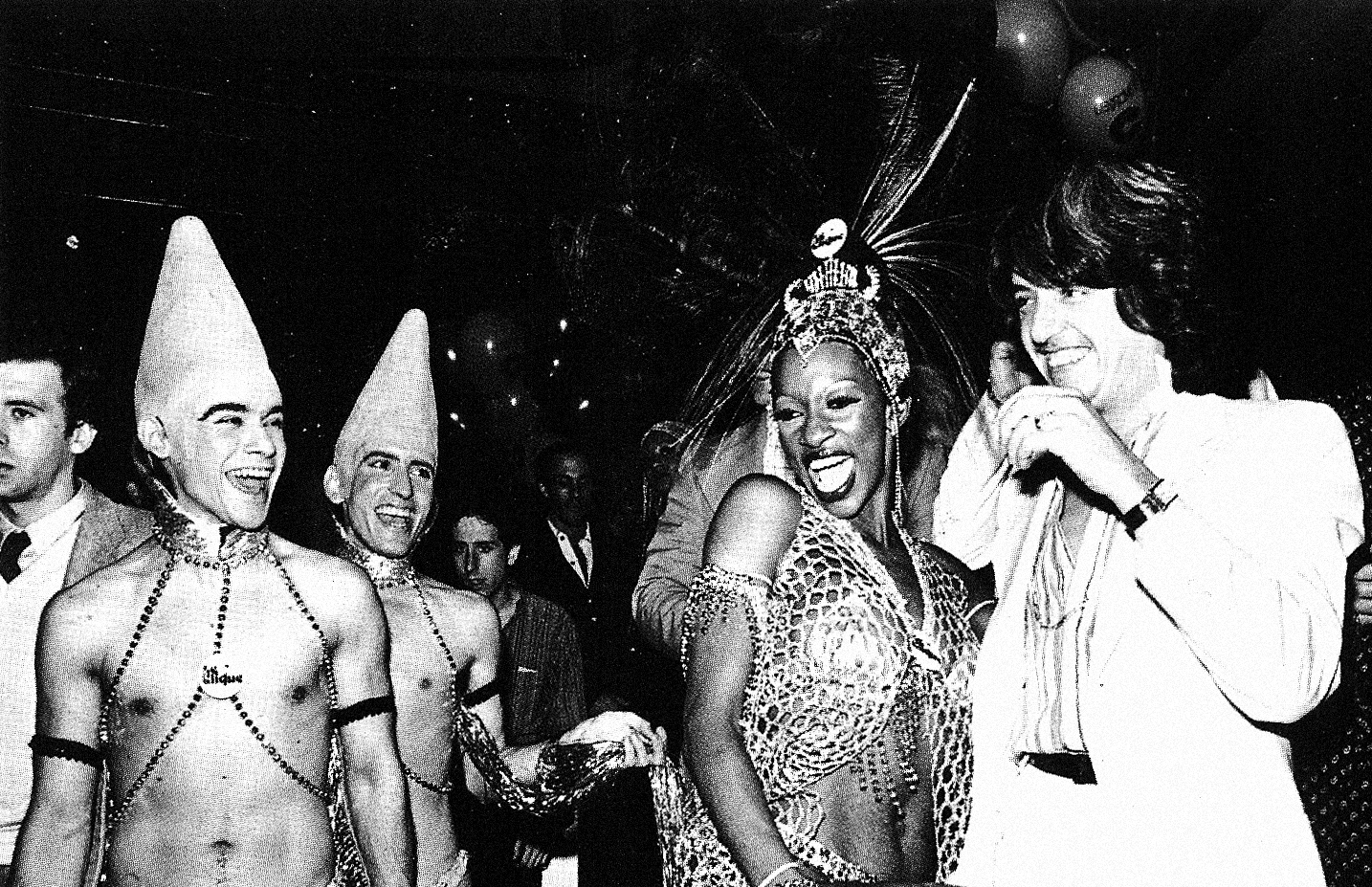

The 70s were clearly a wild time for Cerrone on both sides of the Atlantic. In New York, he was not only filling dancefloors at clubs like Studio 54, his strong sense of rhythm was informing an inchoate art form that would later become known as hip hop, with his beats being looped at block parties by the likes of DJ Kool Herc. How did he feel about that?

“I was flattered, especially at the time, but I also had this nagging feeling that I was being looted. But then I let it go, especially when Run DMC sampled my drums. Flattery took over.”

At Studio 54, he got to hang out with Andy Warhol, Grace Jones and Jean-Paul Goude, Jean-Paul Gaultier and a young Jean-Michel Basquiat. What was Andy Warhol like?

“He was very nice, and he would always ask me to sit at his table. I still remember some of those evenings going on until the morning… but I’ll not reveal anything.”

Why not?

“I cannot say anything about that,” he protests. “When I met Warhol, it was in a club. Between the walls of the club there’s the alcohol and the coke and whatever else. And then you finish up the night at 5am in an apartment or whatever, and specifically, this period was so sex! so I’m not prepared to go into the details…”

Cerrone has come full circle with ‘DNA’, though perhaps there’ll be less sex this time. How does he keep things fresh almost half a century deep into a career?

“Oh, I have so many projects that are still in my head and I never have enough time!”

And how does he feel looking backwards? He says he doesn’t. But he does say, “I’ve greatly exceeded my goals and objectives already”.

When Daft Punk released ‘Random Access Memories’ in 2013, paying homage to their forebears, Cerrone was conspicuous by his absence. Did he feel left out?

“Not exactly,” he replies, thoughtfully. “Of course, I would have been very happy to have been a part of that record, but I wasn’t shocked or anything like that. I mean, why would I be? I was sampled two or three times on the early Daft Punk albums. The influence is clear, so it would be logical for me to be a part of it, but it’s OK that I wasn’t.”

Does he feel bands like Daft Punk and Cassius based a lot of what they do on what he’d done before them?

“Without being pretentious, yes, of course. The large number of samples that are associated with me in international hits by these artists, and many DJs as well, allows my back catalogue to age well. It opens my music up to generation after generation. I’d like to say thank you to all of you.”

‘DNA’ is out on Because