A new film about Conny Plank reveals the pivotal role the legendary German producer had in shaping the 1970s music scene, including his production credits for Kraftwerk, Neu! and Cluster. Stephan Plank, Conny’s son and the film’s co-director, turns the spotlight on his father’s legacy

Tokyo, 1987. It’s nighttime and the city is a riot of colour and noise. A large man with a pair of headphones and a recording device roams around the tacky mirrored sci-fi splendour of a pachinko parlour. The air is alive with the constant clacking of silver metal balls and the chiptune blips and blurts from the arcade machines.

Outside, he pulls off the headphones. Bathed in the neon glare of the parlour, he ruminates briefly on his sound safari.

“I’m trying to find with this noise if it’s possible to make music out of it,” he breaks into a broad, warm grin before he continues. “It’s like at the beginning of music. The human being listened to noises of animals. There are noises the human being doesn’t like, and other noises he does like, and those he likes he picks up and turns into music. Any noise has the potential to be music if it’s liked by a human being.”

A few months later, Conny Plank, the man in the video would be dead aged just 47, having finally succumbed to the cancer he had fought off the year before. His son Stephan, who was with him on that Tokyo trip, was 13 years old when he lost his dad, and now, 30 years later, he’s doing what he can to ensure Plank’s contribution to music is properly understood and celebrated.

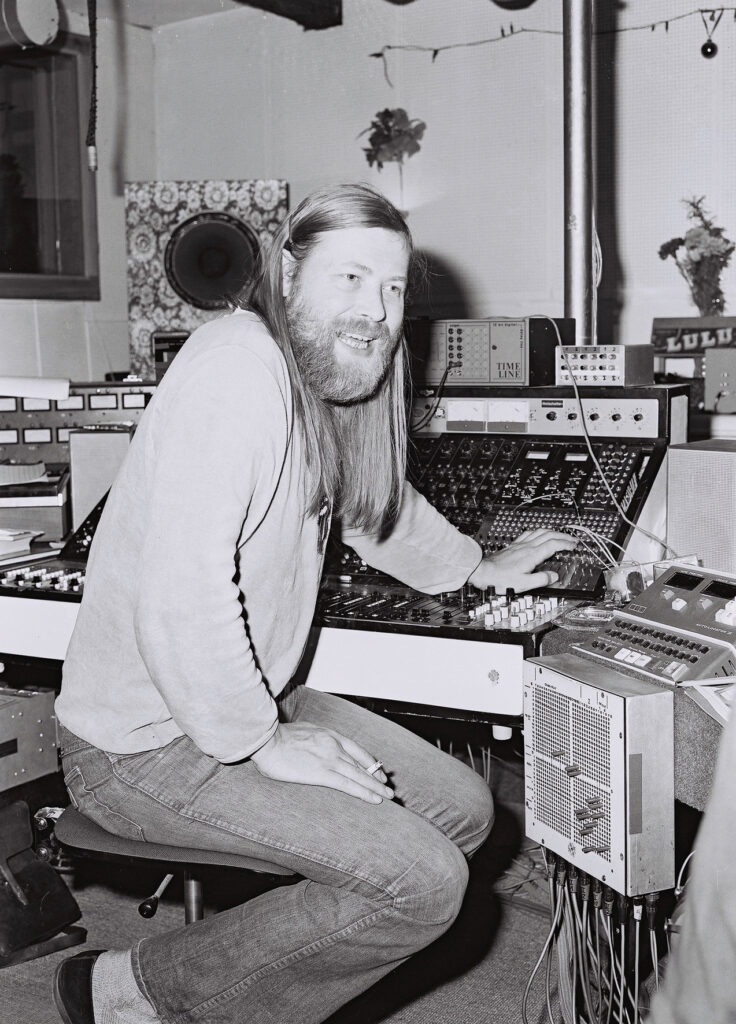

Let’s talk about legacy. Consider, if you will, that Conny Plank’s work with Kraftwerk, Neu! and Cluster was primary source material for the likes of Eno and Bowie, the post-punk scene and the electronic music revolution ushered in by Mute Records. As a body of work, that would be enough for most, but Plank didn’t start or even stop there. Now a film project, ‘Conny Plank: The Potential Of Noise’, finally tells the full story.

“In 2006, when my mother Christa died, I was sitting at my computer feeling very sad, googling my father’s name,” says Stephan, “which was when I found that first scene you see in the film, it was a moment when something clicked.”

Stephan knew he needed to make a film about his father’s life and chose the Tokyo footage to start what was, at times, an emotional journey of discovery, tracking down and talking to members of the many bands who came into Conny’s orbit.

For Stephan, nearly 30 years on, his father had become a “phantom, a blur”. To everyone else, Conny Plank was the man behind the beauty and savagery of Neu!’s krautrock blueprint, the technical wizard who helped pave the way for Kraftwerk as they mutated from avant-garde outliers to electronic music superstars.

Before Kraftwerk, Conny had recorded Duke Ellington and worked with Stockhausen. His studio provided Brian Eno with a kind of German finishing school for his own considerable production skills. Eno spent a decent chunk of 1978 at Conny’s place producing Devo’s ‘Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!’, and working on ‘After The Heat’, his collaboration with Cluster’s Dieter Moebius and Joachim Roedelius. Cluster, Guru Guru, La Düsseldorf, The Tourists, Eurythmics, DAF, Killing Joke, Holger Czukay, Harmonia, Scorpions, the embryonic Underworld, and more, all of them were scooped into the warm sonic embrace of Conny Plank.

“Conny was at the centre of it all,” says John Foxx, who doesn’t appear in the film, with Midge Ure being the chosen Ultravox spokesman. Conny, remember, also produced their chart-shattering 1980 album ‘Vienna’ long after Foxx had jumped ship. But the 1978 Foxx-led Ultravox sought out Conny when they were looking to make their influential ‘Systems Of Romance’ album.

“He was the human crossroad between German electronic music, avant-rock, experimentalism and the remains of the spirit of Brit psychedelia, all the things we loved,” adds Foxx. “No other producer in the world was anywhere near all that.”

So how did Conny Plank become that catalyst for so much thrilling music? It’s the question that Stephan’s film tries to answer, while bringing him back into focus for the child who lost his dad all those years ago.

Conny Plank was born in 1940 in Hütschenhausen in south west Germany, and was first turned on to music thanks to broadcasts emanating from the huge American base at Kaisterslautern, aka K-Town. Its transmitter – beaming jazz and, later, rock ‘n’ roll to homesick US military personnel – was located just 25km from his bedroom. His career as a studio engineer started with West Germany’s national broadcaster WDR in the mid 1960s. He worked in the station’s studio in Cologne, mostly producing schlager, the middle-of-the-road sentimental jolly pap so adored across swathes of northern Europe.

However, the Cologne Studio For Electronic Music was also located at WDR, where Stockhausen and his students (including Holger Czukay) worked. Czukay recognised a fellow traveller in sound when he met Conny, and introduced him to Stockhausen. Conny’s musical world was opening up.

In the late 1960s, he left WDR for the Cologne Rhenus Studio. At Rhenus he worked on a clutch of free jazz albums in 1969. This stuff wasn’t easy listening. In the space of a few months he helmed albums by New Jazz Trio, Alexander Von Schlippenbach, and Peter Brötzmann Sextet. The latter’s album, ‘Nipples’, included British guitar abuser Derek Bailey, which might give you an idea of what to expect from those records.

The Manfred Schoof Sextett were also a part of this Rhenus avant-jazz recording scene. Their drummer was Jaki Liebezeit, who was just weeks away from joining Can with fellow studio haunters Holger Czukay and Irmin Schmidt. This was all edgy gear, on the cutting edge of what people considered music, which puts what he was about to do with Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider into a context that is usually overlooked.

One session in the middle of all this was more traditional, but a critical moment for Conny Plank. Duke Ellington had booked the studio for a rehearsal and Conny, a huge fan from his obsessive radio listening days, managed to upgrade the rehearsal to a recording session.

“Around the kitchen table, there was always this tale that dad had recorded Duke Ellington,” remembers Stephan. “He said that he loved jazz, but wasn’t sure about his engineering skills. When Duke Ellington needed a place to rehearse in Cologne, he talked his studio manager into it, and then when the rehearsal was over, my father said, ‘Shall we do a recording?’. After the session, Duke Ellington said, ‘Son, you’re doing good sound’. That’s the day my father thought of himself as a recording engineer.”

It was 9 July 1970, and the tapes were discovered in the Plank archive and released by Groenland in 2015.

Between 1969 and 1970, Conny also recorded a raft of proto-krautrock outfits, including Andromeda, whose solitary album is now as rare as hen’s teeth, Gomorrha (three albums, all bombed, each now worth hundreds of pounds), and Organisation, Ralf and Florian’s “other” band, which ran alongside the Kraftwerk project for a few months.

By 1971, Conny was working at Star Studio in Hamburg, where he produced Cluster (the start of probably his most abiding musical relationship), and engineered Manuel Göttsching and Klaus Schulze’s project Ash Ra Tempel. It was also there that he produced Guru Guru, Ibliss, Jane, and the debut Kraftwerk album, the first of four they made together. It was while recording ‘Kraftwerk’ that he met Michael Rother, and within months he and Klaus Dinger made the first Neu! album with Conny at the controls.

Kraftwerk are conspicuous by their absence in the film. They weren’t interviewed and no music of theirs appears. Did Stephan try to talk to them for the film?

“Of course.”

What did they say?

“They weren’t interested in doing an interview.”

Ralf and Florian famously cut loose from Conny following the success of ‘Autobahn’, after which they produced themselves in their secretive Kling Klang studio. John Foxx remembers talking to Conny about Kraftwerk when he recorded with him.

“He said he disliked the direction they were taking with their new image. I think he felt it was all too close to the Germany everyone else was escaping from,” he says. “Also the music wasn’t fluid or ambiguous enough for him. He felt they were busy constructing some kind of tight prison for themselves.”

Conny had produced ‘Kraftwerk 2’ and ‘Ralf And Florian’, before embarking on ‘Autobahn’ in 1974, which was important for all kinds of reasons, not least because it was mixed at Conny’s new studio, his own. It was in Wolperath, in the countryside south of Cologne, and it was the place that would be Stephan’s childhood home.

“It was an old farmhouse and the studio was in the barn,” remembers Foxx. “It wasn’t modified with tons of soundproofing and acoustic work, Conny wanted a natural, realistic sound and the walls were timber and plaster and pretty uneven, so he knew it would make a reliable recording environment, certainly much truer than most London studios we’d used.”

In 1978, just as Devo were finishing off their hotly anticipated debut album, Ultravox arrived to record ‘Systems Of Romance’ and found a creative hub unlike any other.

“I remember Brian [Eno] working on Devo’s first album,” says Foxx. “I used to chat to them in the courtyard when we were taking a break. There were other buildings set up for recording and editing around the cobbled courtyard and some workshops where a few guys came in to modify and build equipment that Conny had ideas for.

“At any one time there might be several sets of people working there. We used to drop in when we were on tour. At various times, we found Eno working with Devo, and Holger working with Conny, painstakingly editing together his ‘Movies’ album.”

As the workload at Conny’s studio increased, Eno helped recruit a house engineer in 1977. Dave Hutchins was working at Island Records’ studio in west London and had engineered ‘Before And After Science’ (and would later work on ‘Music For Airports’ at Conny’s studio). Eno introduced Hutchins to Conny, and by December he’d upped sticks and relocated to Germany.

“Conny was very experimental,” Hutchins told me when I interviewed him in 2014, “and I was more conventional, it was a good combination. He would go out on a limb and do some very bizarre stuff.”

Hutchins, who died suddenly last year, remembered Bowie visiting the studio, still intending to produce Devo’s debut which ended up as yet another Eno-at-Conny’s production.

“They were not easy sessions,” said Hutchins about Devo. “They had some expectations that were pretty…inflexible. Eno, like Conny, was experimental, and would try off-the-wall ideas. I was never sure if it wasn’t off-the-wall enough for the band or too off-the-wall.”

If Conny wasn’t entirely at ease with the sessions, he would melt away, leaving Hutchins to take charge.

“I wasn’t really doing shifts with Conny, but we split the work,” he told me. “The feeling I had was that he did a bit of work with Devo and then felt it wasn’t for him, and that’s why I ended up taking over the helm at the desk. If Conny was keen on something he would get stuck in and he was king of the show. That was his nature.”

The relationship between Eno and Conny was key to both of them. It’s clear that when Eno and Bowie discovered the German music that shifted Bowie’s axis from his LA plastic soul phase to his exploration of austere European electronics, it was Conny’s work with Neu! and Cluster in particular they had in mind. Bowie even tried (and failed) to recruit Neu!’s Michael Rother for the Berlin sessions. In the film, Rother wastes no time in spelling out just how critical Conny Plank was to Neu!’s achievements.

“It’s impossible to talk about my music,” Rother tells Stephan in the film, “without mentioning Conny Plank. When you’ve got loads of great stuff in your record collection with his name on it, you’d be right to suspect the man must have been amazing.”

And Eno knew exactly what he was doing when he immersed himself in Germany’s new music. He went straight to the source, to Conny Plank.

“I have very fond memories of Brian,” says Stephan. “He was such a good friend to my father. I think they had great respect for each other, there were no hard feelings. He was a very good friend to my mother as well. Brian tried to get my father working with U2 for ‘The Joshua Tree’, but my father couldn’t work it out with Mr Bono. Brian did, but he first tried to give it to Conny.”

Conny is famously supposed to have said, “I cannot work with this singer…” and that was that.

When Conny died on 18 December 1987, the studio was heavily in debt. Business, most people agree, was not his strong suit. His wife, Christa, took over the running of the operation, and later Stephan became studio manager. He also started managing German singer and “punk godmother” Nina Hagen. In 2006, when Christa died, the studio was still in debt, to the tune of €400,000. Stephan shut up shop, and set about archiving what needed saving, and junking the rest. The mixing desk was sold to Dave Allen, the London-based producer and engineer known for his work with The Human League (he engineered their ‘Dare’ album) and The Cure, among many others.

In 2010, Stephan’s daughter was born, and he decided to take time out of his management duties and focus his energies on securing his father’s legacy with the film and releasing some of his archive material.

First there was the four CD boxset, ‘Who’s That Man’, released by Groenland in early 2013. It spanned Conny’s career, with highlights like ‘Broken Head’ from the 1978 Eno, Moebius and Roedelius album ‘After The Heat’, obscure gems like Psychotic Tanks’ ‘Let’s Have A Party’ from their cassette-only album ‘Studio’, and big hitters DAF, Neu!, Eurythmics and La Düsseldorf. The krautrock supergroup Harmonia (Michael Rother with Moebius and Roedelius) were missing, but there are plenty of excellent Conny Plank collaborations on board, and an extraordinary 14 minutes from Ibliss, a band put together by a couple of former members of the pre-Kraftwerk band Organisation, whose solitary 1972 album ‘Supernova’ is a collector’s item of truly berserk value. Its Clangers-meets-krautrock cosmic freakout is quite the trip. And most recently there’s been the spectacular DAF boxset.

“It’s everything we could find in the archive,” says Stephan of the DAF collection. “We digitised it all from the original 24-track two-inch tapes, which was quite a challenge. You have to bake the tape at certain temperatures to remove the humidity so it isn’t destroyed the first time you play it after 30 years.”

There’s no Devo in the archive, so the multitrack tapes that apparently featured layers of unused Eno synth work and even Bowie backing vocals remain lost.

There’s a poignant moment in the film when Stephan is speaking to Holger Czukay, now also sadly no longer with us. He tells Stephan that he is “very much Christa’s son”, that Conny didn’t have much time for Stephan and would shoo him from the studio. How did hearing that make him feel?

“To be honest, this is the perception of a musician who was working a lot with my father,” says Stephan. “I didn’t have the feeling that my father was so absent, but then again when you grow up, whatever your dad does is normal. I didn’t feel unappreciated by him, it was more like, what a great dad to have. The fathers of my friends went away in the morning and came back at five o’clock and were tired from work. I could go to the studio whenever I liked and talk to my father. He would rush me out after a time, but he was a great dad to have.”