Let’s get this straight: David Bowie was the godhead of 1970s electronic music. It was through him that electronic music was understood by a mass audience. His unique ability to synthesise, in both senses of the word, opened up pop music and revealed new ways of creating it, ways which would rapidly mutate and produce beautiful (and gloriously ugly) offspring in quick succession.

He wasn’t the first to make electronic music by a long chalk (he never was the first at anything, but he was often the best), but his intervention in electronics was a catalyst, an investment of extraordinary energy that resulted in a chain reaction, which we’re still living with today.

In January, Momus, the long-time avant-garde pop musician whose own life and work has a similar restless intelligence to Bowie’s about it, wrote in his heartfelt eulogy that Bowie “became a worldwide electronic art school, launching a thousand careers in art, media, acting and performance”. He meant “electronic” as in the recorded music and broadcast technology that beamed Bowie into the heads of generations of outsiders like himself and inspired them to make something creative of their lives. Momus also knows that Bowie was the electronic music lightning rod of his era.

From Philly Dogs To Kraftwerk

Bowie was relatively late to the electronic music party, but when he did arrive, in that way he had about him, he lit the place up and took it to a whole new level. He had moved to America in 1974 – New York at first and then Los Angeles – when the sound of young Germany caught his ear. With his legendarily low boredom threshold gaining almost terminal velocity in America’s frenetic atmosphere and further exacerbated by the industrial quantities of cocaine he was ingesting, he had already ditched the ‘Diamond Dogs’ concept halfway through a two-leg US tour, rebadging it ‘Philly Dogs Tour’ and recording ‘Young Americans’ in Philadelphia during the tour break. His audience had scarcely digested this new sound when Bowie’s restlessness was already pushing him towards another new one.

“My attention had been swung back to Europe with the release of Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ in 1974,” he said. “The preponderance of electronic instruments convinced me that this was an area that I had to investigate a little further.”

For Bowie, there had been just the tiniest smidgen of electronics in the past. ‘Andy Warhol’ from 1971’s ‘Hunky Dory’ has a burbling synth in the intro, presumably from a VCS3 that was lurking about in the studio, and there was the Mellotron on ‘Space Oddity’, of course. And as it did with electronic music itself at the time, an air of science fiction clung to Bowie. There were the outlandish clothes and the make-up, the songs about space, stars, Mars and the Moon, and there were dystopian tropes from actual science fiction like ‘1984’ (which, had he got permission, would have formed the thematic basis of ‘Diamond Dogs’). There was his defining role in Nic Roeg’s ‘The Man Who Fell To Earth’ too.

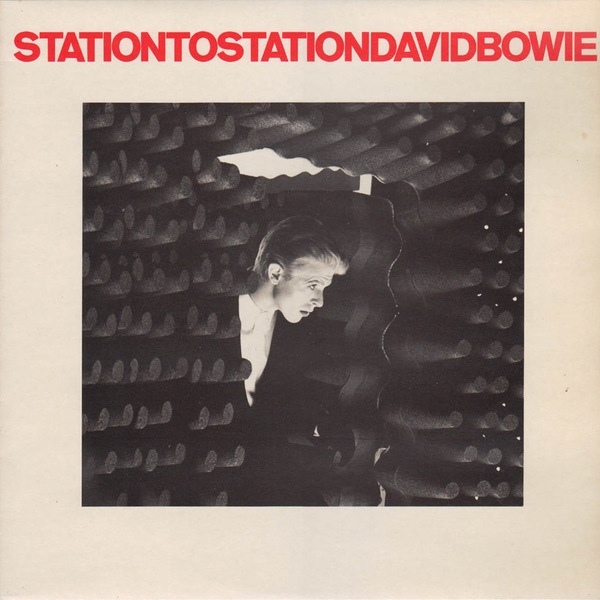

It wasn’t until ‘Station To Station’, though, recorded just seven months after the release of ‘Young Americans’, with its austere opening of white noise, that Bowie really started embracing synths to make new music. His new favourite electronic Europeans were exerting their influence, ‘Autobahn’ providing a welcome soundtrack to his 1975 LA sojourn, but the inspiration wasn’t as direct as some have claimed.

“One lazy observation I would like to point up,” Bowie said in 2001, “is the assumption that ‘Station To Station’ was an homage to Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’. In reality, ‘Station To Station’ preceded ‘Trans-Europe Express’ by quite some time. And the title derives from the Stations of the Cross, not the railway system.”

Kraftwerk’s first encounter with Bowie was immortalised in the laconically delivered ‘Trans-Europe Express’ lyric: “From station to station/ Back to Düssseldorf city / Meet Iggy Pop and David Bowie”. Former Kraftwerk percussionist Wolfgang Flür well remembers the band’s first encounter with Bowie’s live show.

“We visited David on 13 April 1976, at a concert during his ‘Station To Station’ tour in Frankfurt,” he explains. “We drove in Florian’s huge Mercedes 600 to my home city and had a really good day.”

Kraftwerk were deeply impressed by what they saw.

“I can remember David’s concert blew our minds,” Flür continues. “David had distanced himself from his colourful outfits and chameleon image of the past and went onstage in a black suit and white shirt. The lighting was in different white tones; cold neon-white, powerful and dazzling halogen-white, smooth bulb-white. Different nuances were used for each song. His band looked like classical orchestra musicians, also with black and white suits. The whole event appeared to me to be more like a serious classical concert than a pop concert.

“David had Kraftwerk music playing over the PA as kind of an overture, especially ‘Radio-Activity’. Of course, we were noticed by David’s and our own fans and had to sign, sign, sign everything imaginable! The concert made a big impression on me. I can remember it led to our own style with black trousers, red shirts and black ties. The ties were equipped later with a row of red blinking LED lamps, lit up by batteries each of us had in his trouser pocket.”

Much has been made about the possibility that Kraftwerk and Bowie were going to work together, did Wolfgang know anything about it?

“Ralf and Florian had a couple of discreet meetings about the possibility of working together, maybe on an album and a tour,” he says. “I was very disappointed that Ralf and Florian decided against it, I must confess. The thought of playing for David with my electronic drum pads during a tour was a very exciting prospect.”

“We met a few times socially,” said Bowie of these encounters, “but that was as far as it went.”

Nonetheless, electronic and experimental German music of the mid-1970s was providing Bowie with the creative inspiration that would help propel him out of LA (“The fucking place should be wiped off the face of the earth” was his coke-addled parting shot and he later described the city as a “blister on the backside of humanity”) and land him in Berlin.

By the time he arrived, listening to ‘Autobahn’ while tooling up and down the freeways of LA was ancient history in Bowie’s quicksilver life. “By Berlin, ‘Autobahn’ was rather last year’s news,” as he put it. The only concrete evidence of the Bowie/Kraftwerk nexus on record is the aforementioned Kraftwerk lyric and the track ‘V2-Schneider’, recorded for ‘Heroes’ just a couple of months after the release of ‘Trans-Europe Express’. “Of course!” Bowie replied when asked if it was a tribute to Kraftwerk’s Florian Schneider. But despite his admiration for Kraftwerk, their approach to music “had in itself little place in my scheme,” Bowie said.

“Theirs was a controlled, robotic, extremely measured series of compositions, almost a parody of minimalism,” he explained. “One had the feeling that Ralf and Florian were completely in charge of their environment, and that their compositions were well-prepared and honed before entering the studio. My work tended to expressionist mood pieces, the protagonist – myself – abandoning himself to the ‘zeitgeist’, a popular word at the time, with little or no control over his life. The music was spontaneous for the most part and created in the studio.”

Nor was there much in common sonically.

“We were poles apart,” Bowie said. “Kraftwerk’s percussion sound was produced electronically, rigid in tempo, unmoving. Ours was the mangled treatment of a powerfully emotive drummer, Dennis Davis. The tempo not only moved, but also was expressed in more than ‘human’ fashion. Kraftwerk supported that unyielding machine-like beat with all synthetic sound generating sources. We used an R&B band.”

Bowie said at the time that he was trying to merge rock ’n’ roll with new processes and it was Kraftwerk’s reaction to American music that really interested him, more than the synthesisers.

“Since ‘Station To Station’, the hybridisation of R&B and electronics had been a goal of mine,” he said later. “Indeed, according to a 1970s interview with Brian Eno, this is what had drawn him to working with me. What I was passionate about in relation to Kraftwerk was their singular determination to stand apart from stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility displayed through their music. This was their very important influence on me.”

Kraftwerk’s influence on Bowie, then, while important and for a while almost obsessional, wasn’t going to find its way into his music in the obvious sense, but it would certainly colour the textures and the intellectual motivation. And if you watch contemporary videos of Bowie performing the instrumentals from ‘Low’, you get the distinct impression that his impassive stillness at the keyboard – most definitely at odds with his usually expressive stage presence – was partly down to Bowie fantasising about being a part of Kraftwerk, if just for a few minutes. But, as ever, Bowie went his own way with the new ideas he had consumed.

From Düsseldorf To Berlin

“I had no real inclination to go to Düsseldorf as I was very single-minded about what I needed to do in the studio in Berlin,” Bowie said. “I took it upon myself to introduce Eno to the Düsseldorf sound with which he was very taken, Conny Plank et al, and also to Devo who in turn had been introduced to me by Iggy, and Brian eventually made it up there to record with some of them.”

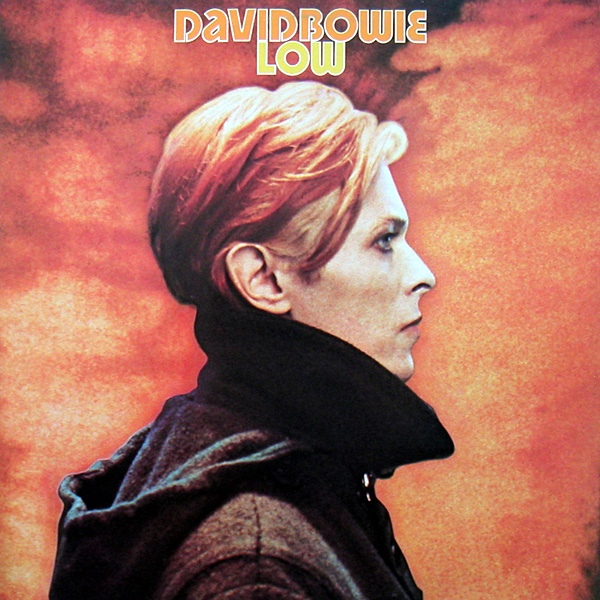

Brian Eno worked with Cluster and would go on to produce the debut Devo album with Conny Plank in early 1978, when it became clear that Bowie wouldn’t have time to do it himself as promised in 1977. Bowie and Eno meanwhile set about the so-called Berlin trilogy with all of this ringing in their ears one way or another. Only ‘Heroes’ was recorded wholly in Berlin, though. ‘Low’ was partly made in France and finished in Berlin, while the often somewhat disregarded third album, ‘Lodger’, was recorded in Switzerland and New York. Bowie called the three albums a triptych (”I’ve always liked that word,” he said at the time, “and I told Eno I wanted to make one, and he said, ‘Well, yes, we better had now you’ve said it’.”) and the Berlin Wall’s oppressive presence made for a compelling psychological anchor for the whole thing.

Bowie tried to recruit Neu!’s Michael Rother for ‘Low’, but the way he told it, got knocked back.

“My original top of my wishlist for guitar player on ‘Low’ was Michael Rother from Neu!,” he said. “Neu! being passionate, even diametrically opposite to Kraftwerk. I phoned him from France in the first few days of recording, but in the most polite and diplomatic fashion he said ‘No’.”

Rother, however, remembered that once the offer had been made, there was no follow-up. He suspects someone in Bowie’s management didn’t want him on board. With or without Rother (but certainly with guitarists Carlos Alomar and Ricky Gardiner, who would also play on Iggy Pop’s ‘Lust For Life’ album), ‘Low’ took the icy European electronic aesthetic of the song ‘Station To Station’ as its start point.

“As far as the music goes,” said Bowie, “‘Low’ and its siblings were a direct follow-on from the title track of ‘Station To Station’. It’s often struck me that there will usually be one track on any given album of mine, which will be a fair indicator of the intent of the following album.”

Half of ‘Heroes’ was made up of electronic instrumentals, featuring processed sounds and a new sound canvas that validated electronic music for anyone yet to discover (or be convinced by) Kraftwerk. It was released in the same year as ‘Low’ and continued the theme of electronic ambient instrumentals, with the rest of the album made up of songs with Bowie in full throat, rousing and upbeat. Taken together now, the two records sound nothing short of miraculous. The enervation of his LA period, when he was half-dead from his drug intake and occult obsessions to the extent that he couldn’t actually remember making the ‘Station To Station’ album, were entirely dispelled. You can hear his spirit returning through the two albums. By ‘Heroes’, Bowie was in fine health.

“My drug intake was practically zero,” he said. “I would eat a couple of raw eggs to start the day or finish it, with pretty big meals in between. Lots of meat and veg, thanks mum. Brian would start his day with a cup full of boiling water into which he would cut huge lumps of garlic. He was no fun to do backing vocals with on the same mic.”

Bowie was at the top of his game, writing and recording ‘Heroes’ in record time, with ‘Joe The Lion’ written at the mic.

“Most of my vocals were first takes, some written as I sang,” he explained. “Most famously ‘Joe The Lion’, I suppose. I would put the headphones on, stand at the mic, listen to a verse, jot down some key words that came to mind, then take. Then I would repeat the same process for the next section. It was something that I learnt from working with Iggy and I thought a very effective way of breaking normality in the lyric.”

As the team gathered to make the final album of the trilogy, ‘Lodger’, the energy had dissipated somewhat.

“I think Tony [Visconti] and I would both agree that we didn’t take enough care mixing,” said Bowie. “This had a lot to do with my being distracted by personal events in my life and I think Tony lost heart a little because it never came together as easily as both ‘Low’ and ‘Heroes’ had. I would still maintain, though, that there are a number of really important ideas on ‘Lodger’.”

Bowie was asked whether ‘Lodger’ represented a departure from pure electronic sounds. Was it a deliberate strategy to stay ahead of the synthesiser copycat bands who were busy aping ‘Low’ and ‘Heroes’?

“I think it’s the lack of instrumentals that give you the impression that our process was different,” said Bowie. “It really wasn’t though. It was a lot more mischievous. Brian and I did play a number of ‘art pranks’ on the band. They really didn’t go down too well. Especially with Carlos, who tends to be quite ‘grand’.”

The pranks included making Carlos Alomar play drums on ‘Boys Keep Swinging’ and having drummer Dennis Davis play bass. During the sessions, Eno got into the habit of purchasing boxes of condoms every morning from a nearby pharmacy, mainly because there was an attractive woman serving there. He would then come into the studio and report on her reaction to selling him yet another box of 24 condoms. After a while, Bowie talked a friend of the studio assistant, an actor, into bursting into the shop while Eno was making his next purchase, pretending to be the shop assistant’s enraged boyfriend. The terrified Eno claimed the condoms were for his fingers, because as a keyboard player they would become bruised and bloody from playing.

In actual fact, the nearest Eno came to being a keyboard player on the record was manipulating the EMS Synthi AKS which, together with Bowie’s drum machine, created the sound of crickets on ‘African Nightflight’, listed as “cricket menace” among Eno’s contributions to the album. But for all the fun and games, the Berlin albums are now widely seen as foundation stones of post-punk, ambient music and electronica, a fact that didn’t surprise Bowie.

“For whatever reason, for whatever confluence of circumstances, Tony, Brian and I created a powerful, anguished, sometimes euphoric language of sounds,” he said. “In some ways, sadly, they really captured – unlike anything else in that time – a sense of yearning for a future that we all knew would never come to pass. It is some of the best work that the three of us have ever done. Nothing else sounded like those albums. Nothing else came close. If I never made another album, it really wouldn’t matter now, my complete being is within those three. They are my DNA.”

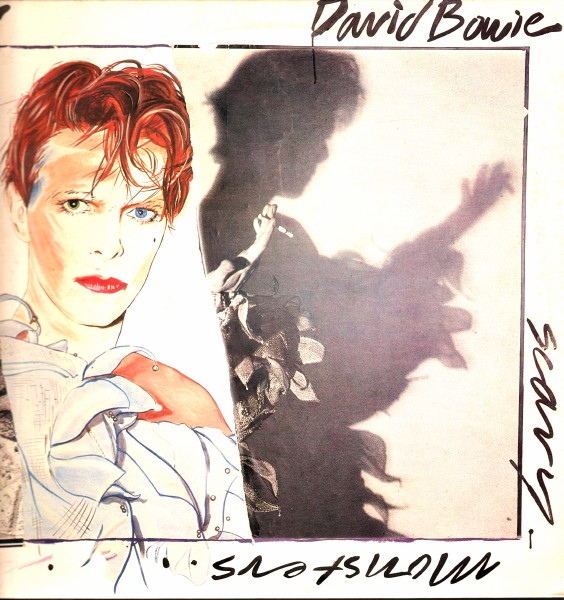

They are also in the DNA of the legions of synth and new wave bands who came after those three albums. In one of the full circles which seem to emanate from so much of what Bowie did, his next album, 1980’s immense ‘Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)’, rounded on the Bowie-in-Berlin-inspired electronic futurists, gathered them up to its Pierrot/Harlequin costumed chest, and took them back to school, delivering the genre-defining Number One single (and video) ‘Ashes To Ashes’.

“‘Scary Monsters’ is never mentioned as being part of the three albums,” said Tony Visconti, “but I think it is the crowning glory of what we had learnt from making the triptych. Even though Brian wasn’t with us on that one, you can feel his influence.”

One anecdote from the ‘Scary Monsters’ period that bears repeating was told by Bowie to a lighting engineer called Michael Dignum on a video shoot in 1993 for ‘Miracle Goodnight’ from ‘Black Tie White Noise’. In a few moments of downtime, Dignum asked Bowie if there was a moment from his career that stood out in his memory. He recounted the tale of when the shoot for the ‘Ashes To Ashes’ video (“Do you know the one?” Bowie asked) on Hastings beach was interrupted by an old man taking a walk. He strayed into shot and filming was halted. The director came running up and said to the old man, ‘Don’t you know who this is?’. The man looked Bowie up and down, dressed as he was in full make-up and costume, and said, “Yeah, it’s some cunt in a clown suit”.

“That was a huge moment for me,” Bowie said. “It put me back in my place and made me realise, ‘Yes I’m just a cunt in a clown suit.’ I think about that old guy all the time.”

The ‘Ashes To Ashes’ single only made it to number 101 in the US charts, and in retrospect Bowie’s first album of the 1980s would feel more like a love letter to the 1970s, kissing goodbye to that future he envisioned as it disappeared in the rear-view mirror. The rest of Bowie’s 1980s output saw him cementing his place in the first division of superstardom, embarking on a successful chase for Yankee dollar denied him during his experimental Berlin period. It was a time during which he made the least interesting music of his entire career.

Welcome To The Machine

As the 1990s approached, Bowie was floundering. He’d had enough of the MTV stadium-friendly version of pop stardom, and trashed it with his widely derided Tin Machine project, a “band” in which he was just “one of the guys”. No one bought the concept, but he seemed determined to make it stick, releasing two albums and making videos featuring carefully choreographed flailing stage divers to emphasise the band’s authentic post-Pixies rockin’ democracy. It was the most inauthentic stab at authenticity from the master of all rock ’n’ roll poseurs. Tin Machine made most Bowie fans sad and confused, but at least it kicked the stadium podium from under him and acted as an emetic, purging Bowie of glitzy 80s superstardom, preparing him for what was to come next.

The 1993 album ‘Black Tie White Noise’ had a title inspired by synthesisers, with Bowie also casting white noise as the music made by white people, the black tie referencing the black music he loved, and his own connection to it (his black ties). It wasn’t an electronic album per se, but clearly Bowie was interested in what was going on in the vanguard of electronic music, commissioning remixes from Leftfield, Brothers In Rhythm, Grant Showbiz, and Jack Dangers from Meat Beat Manifesto.

It was ‘Outside’, released in 1995, which marked an extraordinary new immersion in electronic music for Bowie, just at a time when Britain was in the throes of the vacuous Britpop era. Bowie wasn’t interested in the flag-waving nostalgia of laddish Britpop, and pinned his colours to the alternative 1990s musical narrative; one of dark, atmospheric and experimental electronic music. The album saw Brian Eno back in a warm embrace with Bowie for the first time since the fabled Berlin trilogy. The associated tour, a double header with Nine Inch Nails, started before the album was released and saw Bowie having to make his case to a young audience barely aware of him.

‘Outside’ was a concept album, based in part on a series of interviews Bowie and Eno undertook with patients at the Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic in Vienna. The clinic’s pioneering art therapy techniques spawned a movement called Outsider Art or Art Brut. The album was a metaphysical detective story with a fractured narrative about an investigation into thefts of body parts by artists who clearly have got a little carried away with the whole body shock art concept; a kind of sci-fi YBA Burke and Hare private dick mash-up, with a healthy side of sex and violence a la the Jim Rose Circus.

“I was interested in the re-emergence of neo-paganism, ritual body art, fragmentation of society,” said Bowie. An idea that he and Eno had for ‘Outside’ was for it to be another ongoing project, a bit like the Berlin triptych, “a diary of what it felt like to be around at the end of the millennium”, as Bowie put it. He consciously took elements of his 1970s work and put it into ‘Outside’.

“It’s almost like the albums that I’ve done have become the palette I can draw from, each album’s a different colour,” he explained. “I don’t have to go much to the outside for influence or a new inventive way of doing something, I just look at my own stuff and utilise what I’ve done already.”

In ‘Outside’, Bowie said, “there’s a kind of angst that was in the late 70s albums. The album is about atmosphere. The sound of 1995.”

It’s hard to pin down exactly what ‘Outside’ is. It’s rich and ornamented, with Mike Garson’s piano work (he’d played on ‘Aladdin Sane’, ‘Diamond Dogs’ and ‘Young Americans’) immediately identifiable. It’s also very long and covers a lot of styles, but at its root it relies on machines for much of its texture, like the pulsing ‘No Control’ and the frantic ‘Hello Spaceboy’, the latter echoing ‘Beauty And The Beast’ (the opening track of ‘Heroes’) buried in it, literally, in what sounds like a submerged sample. ‘We Prick You’, another fast and hard moment, takes a hypnotic and repetitive tone as its hook, and the breakneck bpms suggest Bowie was starting to absorb the frenetic and paranoid flow of jungle and drum ’n’ bass, although when asked about the influences on the album, he cited The Young Gods of all people (maybe because he was living in Switzerland by this point, home of The Young Gods).

‘Outside’ is dotted with spoken word vignettes, heavily processed with Bowie doing his funny voices, the like of which we hadn’t heard since his 1960s recordings like ‘Mr Gravedigger’, and reminiscent of the opening of ‘Diamond Dogs’. The whole thing is punctuated with guitar growls and various other sound effects, but in its overall texture it takes the moody atmospherics of underground electronic music as practised by the likes of Nine Inch Nails, Marilyn Manson and The Prodigy as its sound world. It’s a palette more suited to films about serial killers than as a soundtrack for Cool Britannia.

Its failure, if there is one, is that its theatricality disjoints the album’s coherence. It suggests itself as a series of stories and characters, rather than a collection of musical moments that are calculated to come together into a glorious album. It’s messy, dark and, make no mistake, is vintage Bowie in full art-pomp.

Ground Control To Planet ‘Earthling’

Bowie’s next album, the end-of-millennium diary concept dropped, was the 1997 drum ’n’ bass-inflected ‘Earthling’. It merged the jacked-up bpms of inner London with the industrial electronics of Nine Inch Nails and all the dark aggression that suggests. Ever the fan, Bowie was genuinely thrilled by jungle.

“When I first heard jungle I just thought, ‘God, this is one of the most exciting forms I’ve ever heard. It’s the future of rock!’,” he said. “I guess it’s how rock was for the generation behind me, when it kicked in around ’56 and everyone thought, ‘What is THAT?!?’. I’m still like that, still fan-like enough that when I hear something really new I go, ‘I don’t wanna be here, I wanna be THERE’. I remember exactly the same feelings the first time I heard The Who. That’s what jungle did for me.”

The cover art features Bowie with his back to us, wearing a Union Jack coat, gazing out across what may well be the English countryside. There are at least four pretty stellar tracks on ‘Earthling’: ‘Little Wonder’, ‘Battle For Britain’, the crunching industrial synth rock paranoia of ‘I’m Afraid Of Americans’ and ‘The Last Thing You Should Do’. The album was presaged (via an internet release – in 1997 this is) by ‘Telling Lies’, which was mixed by A Guy Called Gerald.

Like ‘Outside’, when taken out of the context of the 1990s, it’s a great Bowie album. But it drew some critical ire for the perceived appropriation of a genre that Bowie, according to some sections of the media, had no right to be fooling around with. He’d got the same heat for his Philly soul sound on ‘Young Americans’ back in 1975, but the critical atmosphere of the late 1990s was less forgiving and more divisive. But Bowie, as ever, managed to bring something to a newly popular form. Using sampled drums and 160bpms in the epic ‘Little Wonder’, with some belching electronics and samples across it, he welded the whole thing to a great melody. The same goes for ‘Battle For Britain’, another drum ’n’ bass dabble, which soon lifts into a vintage Bowie tune.

“If jungle’s not my beat, what is?” he asked, alluding to his south London roots and his heavy-duty urban electronic CV. “I don’t think you can be that territorial over a beat. In five, six years it’ll be forgotten exactly what or who the roots of jungle were. At this moment, it’s such a tight ownership that anybody who infringes on that ownership, unless they have the authentication of at least living in the city where it was founded or being in the right age group, then they’re going to be terribly suspect.”

Bowie came out fighting his corner. Before the album was released, he was asked if he’d had any grief from the dance music purists.

“No, but I expect it when the album comes out,” he replied. “But honestly, I really don’t care. Why should I? Because I know how good it is. What I’ve done is a lot better than the stuff that I’ve been buying, frankly. There’s only a few records I think are really good, a lot of them are really naff, and I think they have less right to be in jungle than I do.”

In the end, ‘Earthing’, like ‘Outside’, ‘Young Americans’ and much of the Berlin trilogy came down to the same Bowie modus operandi.

“It was the hybridising of the European and the American sensibilities, and for me, that’s exciting,” Bowie said, “That’s what I do best. I’m a synthesist.”

On ‘Where Are We Now?’, the first track to be released from 2013’s album-out-of-nowhere ‘The Next Day’, Bowie referenced the areas of Berlin where he used to live, closing another circle, this time with himself. The album cover art used the same Masayoshi Sukita image from ‘Heroes’, slapping a white square over it, and crossing out the title ‘Heroes’. It appeared to be making some kind of final, beautifully melancholy statement. But right to the end, Bowie was synthesising.

It was only fitting that his final album, the impressive and dense ‘Blackstar’, a record we’re all still processing, should reveal Bowie at his most vulnerable and honest, his creativity not cowed by his illness, but apparently inspired by its grim deadline into a final glorious flowering.

Throughout his career, David Bowie synthesised the modern world for us. He somehow made sense of it by inhabiting it. He absorbed cities through their music, and made them romantic and essential to our own lives, even though we might have never visited them ourselves. He was able to make even the Cold War into a manageable creative backdrop for those of us old enough to have been terrified by it. And then he came home to London to check out the synth futurist upstarts and became a cunt in a clown suit for our entertainment.

Bowie Remembered…

Mark Moore

“I was broke most of the time in my younger days, so I would make some cash by working as an extra in films. One day, a friend told me she had been asked to be an extra in David Bowie’s ‘Blue Jean’ video. A special version was being made for the US and filmed at the Wag Club in London. I decided to gatecrash it, so I sneaked in to wave my arms around for a few hours while Bowie performed, then hopefully receive the princely sum of £50 at the end. How brilliant was that? Seeing Bowie and getting paid for it! And £50 was fortune back then.

“At the end of the day, I joined the queue to get my wages but was asked where my booking form was, which of course I didn’t have. They told me that they weren’t going to pay me without the form. Just at that moment I saw Bowie walking past, so I marched up to him and said, ‘David darling, they are refusing to pay me. I’ve been here all day waving my arms around and they won’t pay me’. ‘Oh that’s terrible,’ he said. Without any hesitation, Bowie demanded that they gave me the money and sorted the whole thing out. It meant I would be rich for the week. The fact that he was busy shooting his video and performing the whole day, yet he found the time to help someone out really impressed me. What a man. I will never forget his act of kindness.”

John Foxx

“In 1976 we were recording the first Ultravox album at Island Records’ studios in Hammersmith with Brian Eno and Steve Lillywhite. It was early days for everyone, including Brian as a producer, but he clearly had lots of ideas about where to go next, even though he still seemed a bit off-balance after leaving Roxy.

“One day, Eno got a phone call. He’d been contacted by Bowie to work on his next album. Eno seemed unsure if he should do it or not. Of course, he was simply playing hard to get, as usual, so we played along dishing out all the usual stuff – ‘Get on with it Brian, a great gig for you and your new career’ – while he listened, pretending to be in some sort of quandary, but really he was quietly delighted. We were all very pleased for him, it was the turning point he needed. From here, he could proceed on his own terms.

“The album and the ensuing work turned out to be some of Bowie’s best, his most innovative and imaginative, with the brilliant Tony Visconti producing and wonderfully warped contributions by Robert Fripp and Eno. Even though there was a predictable tussle among the more conservative critics, that work entirely succeeded in its intended mission. It pulled Bowie right out of the rock and glam swamp and put him in another league, well ahead of most of his generation.

“Most significantly, this was electronic music entering the game in a pivotal way. A major player like Bowie had chosen to use it to reboot his career. From this and other such moments, electronic music would proceed to entirely revise the face, form and function of popular music.

Steve Cobby

“My next door neighbour when I was very young was Jeff Appleby, who was bass player in Hull band The Rats. His best mate Mick Ronson was on guitar. I used to see Ronno walking into Jeff’s and think an alien from outer space was visiting. The first record I owned was ‘Life On Mars’, a gift from Jeff.

“The local record shop, Bolders in Gipsyville, was owned by Trevor’s dad. Trevor Bolder being the bass player in The Spiders From Mars. As you can imagine the walls were pretty much entirely covered in Bowie paraphernalia. It was where I made my debut record purchase, ‘Burning Love’ by Elvis. I recall going into the shop a little later and being taken aback at the original sleeve for ‘Diamond Dogs’ on the wall, with all the dog’s tackle on view.

“A vivid memory is of Jeff and his wife Moira coming round to our house very excited one teatime saying Mick was going to be on TV. Turned out it was on one of my favourite programmes, ‘Lift Off With Ayshea’ and they played ‘Starman’. Jeff hammered that song for days. The tissue thin walls of Campion Avenue allowed us to all enjoy it. Decades later, around the early part of this millennium, I met Trevor through a mutual friend and shared a few ales and he shared a few stories. I mentioned the ‘Lift Off’ episode and he surprised me when he told me it was Bowie’s first-ever TV appearance.”

Stephen Mallinder

“I was introduced to Bowie at a really early stage by a girl who I was sweet on. She was very taken with him and he was playing Sheffield Top Rank just as ‘Space Oddity’ came out the first time. A bit like the girl question, there was this strange alterity, an exotic otherness, that I found fascinating. I guess I was at that transition point and it was the biggest catalyst in me shifting from being a teenage soul boy into someone with pretentions to being an urbane lad with wider ideas and ambitions. Roxy Music and Eno came a little later.

“From that point, Bowie seemed to map my life. You were always vaguely aware of what he was doing and intrigued to know what was coming next, a touchstone for your own progression. In the days of the almighty music press, you were keen to read his interviews to see what he was into, so for many he was an early introduction to people like William Burroughs, Iggy and various off-beat characters.

“When I got to actually meet him at a private party in the mid-80s, I was completely gobsmacked. In awe just because he was in the same room, he disarmed me by walking over and introducing himself. He knew my name and started to tell me how much he loved ‘Gasoline in Your Eye’, which had come out a week or so before. He was charismatic, as we know, but it was more a case of him being like his music – a bit above, mysterious and ethereal, but incredibly familiar, so you made a connection immediately.”

Luke Haines

“It’s all about the Berlin quartet; that’s the two Iggy albums, ‘Low’ and ‘Heroes’. I always think that ‘Lodger’ doesn’t belong with those records (fine as it is) as it was recorded in Switzerland and is an entirely different sonic monster. So that’s four (count ’em) spotless, genius LPs in one year. Has any other major artist managed this? Of course I love them all, but ‘Heroes’ just edges it for me. So you’re Big Dave, ‘Low’ has been met with mixed reviews, a fair amount of confusion among the kids (who are still trying to get the bonces around ‘Station To Station’) and poor sales. Do you come back with a ‘Jean Genie’ pop smash? No. You come back with ‘Heroes,’ a record even more extreme than ‘Low’.

“The ‘pop’ side is less poppy than the pop side of ‘Low’ and the experimental side is just out there. This isn’t the stentorian Balkan electronic folk of ‘Warzsawa’. This is a trip into the heart of Christiane F junked-out cityscape night vision. Man, you really need it when Dave finishes the album with the broken funk of ‘The Secret Life Of Arabia’.

“I got to see Dave when he hosted the Meltdown festival. He played ‘Low’ in its entirety. It was immense. I was invited to the aftershow party as I had also performed, supporting Television. Bolstered by free wine and general levity I decided to have an ‘art argument’ with Tracey Emin. As we traded insults there was a change of atmosphere in the room as David Bowie rushed through flanked by minders. Emin and I gawped and I swear DB caught my eye and gave me the wink. Then he was gone and Tracey Emin and I burst out laughing.”