From sleepy seaside town to thrumming back streets of East London, East India Youth’s follow-up to his Mercury-nominated debut is seeped in the sounds of the city – and it’s a sonic stunner

Shoreditch has always been a noisy, vibrant place. Lying just beyond the City of London walls, out of the puritanical reach of the capital’s administration, gave it an outsider status that flourished over the centuries. Today, despite the collapse of its industries, extensive damage during the Blitz, and the inexorable march of sleek office buildings up Bishopsgate into the heart of the East End’s otherwise untouched core, Shoreditch still retains that independent spirit.

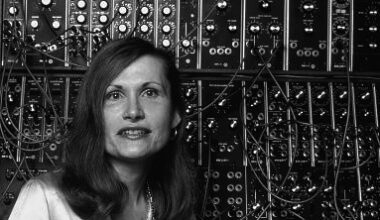

In among that clamour, between hipsterism and the dynamic flows of the City, is William Doyle, better known as East India Youth. By his own admission not exactly the most social creature in the world, Doyle is a complex, solitary figure creating some of electronic music’s least predictable gestures. His recently released second album, ‘Culture Of Volume’, is set to further confound listeners with its surprising cocktail of styles. His journey to the epicentre of London’s creative nexus is a curious one.

“No-one gives a shit about Southampton,” says Doyle, referring to his spell in indie band Doyle & The Fourfathers, an overlooked south coast unit that struggled to find a foothold. “It was hard to keep going, especially as we weren’t based in London. You’re not in the heart of it. It’s why a lot of bands feel they have to gravitate to the city to actually get a foot in the door. We played quite a few gigs in London, but we were never a London band. We reached a point where the momentum just dropped off.”

Disenfranchised by the lack of success, Doyle retreated to the solo electronic pieces he’d been crafting before and during his time in Doyle & The Fourfathers. The result was East India Youth’s debut album, ‘Total Strife Forever’.

“I’d already done half of ‘Total Strife Forever’ by the end of the band,” he says. “I realised I felt so much more involved and invested in those songs than I did with what I’d been doing before. I’d been trying to force some of the things I wanted to do, some of the methods and sounds, into the band. It wasn’t that they were met with resistance, but I felt so deeply connected to them that I knew I was only going to get what I wanted out of them by doing it by myself.”

With ‘Total Strife Forever’ mostly in the bag, there was the issue of how to get his music out of the metaphorical bedroom to a wider audience. A chance encounter at a Factory Floor gig at Shoreditch’s Village Underground in 2012 proved to be the catalyst. John Doran, the editor of The Quietus website, was so taken with Doyle’s music that he established the Quietus Phonographic Corporation label with the sole intention of releasing East India Youth’s first fruit.

‘Total Strife Forever’ was a restless album, full of left turns and unexpected moments; it was utterly modern and defiantly different. Critical to its appeal was its ability to straddle authentic electronic pop songs and dance music tropes. If its success lay in taking the listener on a volatile path, a path that couldn’t be predicted, it is nothing compared to the wild switches and twists of the newly released follow-up, ‘Culture Of Volume’.

Anyone who thought they’d just about got Doyle pinned down on the debut East India Youth album is likely to be left scratching their heads as they are taken off in a series of ever more surprising directions – sensitive ambient passages, euphoric peaks, wild and unstable electronica, and all of it bordered by emotive synthpop.

“I like to make records that will reward people who choose to listen to it from start to finish,” explains Doyle. “I like to take them on a bit of a journey. I like manipulating them when they’re listening to it – I do find it weirdly humorous doing that – but I like eclecticism in records and I’ve always wanted to make eclectic music.”

Marketers and sociologists describe those who have never known anything but the internet as “digital natives”, while psychologists decry the immediacy of mobile devices as creating a generation of impatient, hyperactive, always-on types moving through websites, apps and playlists at high velocity. Some leading lights of the music industry blame that inability to focus on any one thing for the decline of album sales, as listeners amass collections of disparate songs with little genre faithfulness.

The genre-skipping approach could also be the reason why ‘Culture Of Volume’ sees William Doyle, by age at least, firmly in the “digital native” demographic, jumping from style to style so effortlessly, almost recklessly. ‘Culture Of Volume’ is an album that has a buzz, a nowness if you will, suggesting a major leap into a different direction, into multiple different directions, for East India Youth.

Which is perhaps why trying to pin down what makes Doyle tick is something he finds wearing. When asked about influences, he’s not exactly evasive — he’s far too polite and well-mannered for that — but it does seem to bother him.

“It’s a fairly loaded question,” he protests, albeit with a smile. “Maybe you would have had to be there every step along the way for the last 10 years to work it out. Even with the last record, everything jumped from style to style, and I think it’s just because I don’t really feel any limitations with what I want to do. It’s taken me a couple of years to make this record and in that time I’ve been influenced by anything that I’ve listened to more than once. I’m influenced by so much, I absorb quite a lot in that sense, and I shamelessly feel the need to jump around. I think that’s just my style.”

Despite his uncertainty, Doyle clearly feels the need to deliver some sort of response, even if he doesn’t think much of the question.

“This record is a sort of musical diary of the places I’ve been and bands I’ve toured with in the last couple of years,” he continues. “Bands like Factory Floor, Wild Beasts and These New Puritans. When you’re sharing bills with other artists and watching them night after night, it’s hard for their influences not to seep in. What I want to do is take my electronic ideas and combine them with what I consider to be my songwriting past. On the surface of everything are these melodies, so quite immediate pop things, but underneath are layers that might be more electronic.”

If defining his listening habits represents a challenge, it’s nothing compared to the art of writing lyrics. ‘Culture Of Volume’ has a distinctly reflective, maudlin quality, but Doyle is keen to assert that this isn’t intentional.

“The lyrics draw upon experiences of relationships,” he explains. “I don’t just mean in the romantic sense. They’re about my interactions with people and the world around me, but they’re kind of abstracted, they’re not about specific things. They’re there to create an atmosphere of the time I was writing or recording the track, the time it was being made. I’m not just drawing upon a particular relationship or event, it’s just a vague approximation of a feeling.

“I find the whole process of writing lyrics really difficult. I labour over them in a very unsatisfying way. I usually leave the lyrics until last as I don’t have the same pool of unused ideas to draw from. That’s something I really want to change. I’ve started writing down anything recently, even if it’s not going to be used in a song, just to keep my mind ticking over, like it always is with music. The words I just find harder.”

When pressed on the lyrics to ‘The End Result’ or ‘Hearts That Never’, Doyle again becomes politely vague.

“You have to wonder sometimes whether it matters or not,” he sighs. “People like to know that there’s more relevance in lyrics than there needs to be. As long as I think I’ve created an atmosphere with the words, I don’t believe I have to remain true to a feeling or anything. David Byrne and Brian Eno used an approach of just singing gibberish. I believe in that sort of method, because that way the vocal is serving the song and not the opposite way round.”

‘Culture Of Volume’ could be interpreted as meaning many things. One possible explanation is that the world is a more cluttered, noisy place than it was a decade or two ago.

“I look at this album as my London record because I’ve made it entirely while I’ve been living here, unlike ‘Total Strife Forever’, which was made in more of a suburban environment,” he explains. “There’s something about the pace and relentlessness of living in London, but the volume of it is hard to get away from. Living in that urgent environment, it’s almost fucking deafening sometimes.”

And it’s not only his physical self that Doyle has moved this time around. There’s also his signing with the similarly eclectic XL Recordings.

“I’d be lying if I said that I didn’t feel like the right thing to do would be to make an entirely instrumental record,” he laughs. “But really, the reason why this record is more song-based is because of how things have developed with my live performances. I’ve realised that the strength of the live show was in the vocals and how they were given prominence in the set. After doing that for the last couple of years, I wanted to make more vocal-led records. But there’s no pressure at all from XL. It’s only been a blessing.”

At a small showcase gig at East London’s Sebright Arms, a suited, immaculately presented William Doyle looks for all the world like a young auditor letting his hair down after a gruelling day of raking through a City firm’s dirty laundry. In a good way. In a now way.

As with ‘Culture Of Volume’ itself, he opens his set with ‘The Juddering’. Where the album cut sounds like a beatless rave track, sirens and all, the live version comes across like a distended Throbbing Gristle conjured out of the group’s dying corpse, replete with the venue-shaking dynamics expressed in the title.

Doyle’s set is more or less bereft of breaks between songs, almost as if he is embarrassed to receive the obligatory appreciative applause the audience wants to give him. The whole thing further complicates and confounds what was already difficult to fathom in the first place. In a good way. In a now way.

Two albums in, Doyle has so far resisted the temptation of collaborating. He expresses frustration at the frequency with which producers load up their albums with guest appearances. At the same time, he admits that working entirely by himself isn’t necessarily a healthy proposition for the long term.

“I think I’m going to have to make quite a lot of personal changes before I can work with someone else,” he reflects. “I find it hard enough to work if people are in the house at the same time as me. I don’t know whether I just feel a bit embarrassed by the creative process, or maybe the process itself can be a bit ugly and I don’t really want people around when it’s happening. It’s going to take me a while to get over that.

“I don’t get this expectation, especially if you’re an electronics-based producer, to collaborate with other people. It just seems to be the way of the world at present. Everyone’s featuring on everyone’s track, everyone’s producing everyone else. I don’t like that. I’m not that sociable. I’ve got a lot of my own ideas I really need to see out. There’s definitely another record I need to make completely in isolation. Hopefully that will change because I don’t know if I can do this forever. I think something will have to give eventually and maybe I just haven’t found the right people to make that happen yet. I hope I do.”

With such a clear vision of what his music should and shouldn’t be, combined with the stylistic leap into the unknown that is ‘Culture Of Volume’, the thought of a third East India Youth album bodes well. It will no doubt be full of surprises. In a good way. In a now way. Whatever now will sound like by then.

‘Culture Of Volume’ is out on XL Recordings