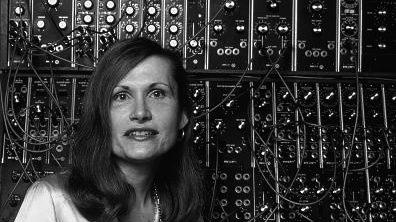

The reclusive synth sorceress Wendy Carlos has granted very few interviews over the last 20 years. This one from 1998, to mark the release of her ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’ album and published here for the first time, offers a candid glimpse at her musical philosophy, her working relationship with Stanley Kubrick, what she thinks of her fellow soundtrack composers and much more…

There’s Bob Moog, surrounded by record company execs, Terry Riley in white robes and a passel of unknown groovers, all trying to get their heads around Columbia’s ‘Bach To Rock’ campaign. Moog is there to demo one of his modular synthesisers, while Riley is improvising on a Farfisa to a swirling backdrop of tape-delayed sounds. Because it’s 1968, it’s reasonable that there’s a bowl of pre-rolled joints on the mixing desk at the back of the room.

“My boss John McClure, who was the head of CBS Masterworks, made these fake marijuana cigarettes that had tobacco in them, and put them in a big bowl at the back of the room,” reveals electronics wizard and composer David Behrman, who produced Terry Riley’s ‘In C’ for the label, many years later. “He was playing it safe.”

Apart from unveiling Riley’s grand minimalist opus, Columbia was also hailing the release of the mostly-forgotten ‘Rock And Other Four Letter Words’ LP: an odd mix of orchestral sounds, chants and interviews with famous musicians of the day put together by rock journos J Marks and Shipen Lebzelter. Today, it’s a dream disc for the sampling community, back then, the A&R wonks probably saw it as a giant step inside the minds of the hip and progressive. Columbia expected to shift an untold number of units. They were quite wrong.

Slipping out of the event after quietly grabbing a copy of the press kit, was a composer who should’ve been making the rounds and glad-handing the suits who were also celebrating her first major release. Wendy Carlos was an unassuming blend of studio engineer and keyboard prodigy who had only so much interest in the limelight. She had put an album together, mostly in her New York City apartment, with the help of composer and fellow Columbia University student Benjamin Folkman. Painstakingly spliced together from tricky multi-track performances, the record was a 40-minute study that looked back towards the canon, and simultaneously ahead into a society that was juggling race riots, Vietnam and space travel. No one was sure what the future would yield, but millions soon came to think that it would sound something like ‘Switched-On Bach’.

Three decades on, Carlos emerged from semi-seclusion to help trumpet the release of her new ‘Tales Of Heaven & Hell’ album, which was set for release along with remasters of a portion of her back catalogue on CD, including the soundtrack to ‘A Clockwork Orange’.

Back then, when print journalism was first nunchucked by the internet, it seemed like everyone was writing all the time for anyone, not knowing who or what platform would be left standing. Which is how I came to be dialing Wendy Carlos one cloudy Saturday afternoon in 1998.

At the time, she was just another synth artist that a now-forgotten editor had asked me to speak with, and not the legendary and reclusive musician who we now revere as much as the vintage gear she once piloted. Our conversation was relaxed and supremely casual, covering topics as mundane as the pollen count in my home state of Georgia and as fascinating as Stanley Kubrick’s obsessive approach to filmmaking.

We didn’t get round to discussing ‘Switched-On Bach’ in any depth, simply because it didn’t come up. In fact, the microcassette that I recorded our interview on would have probably run full had my youngest daughter not entered the laundry room/office I was speaking from to remind me that it was time for me to help me feed her Tamagotchi.

If that call came today, I’d have 10-fold as many questions and would have easily let our electronic pet join the choir invisible rather than politely ringing off like I did 20 years ago. That said, Carlos remains a potent trump card when it comes to telling war stories of the musicians you have and haven’t had the good fortune to chat with. When you mention to someone that you’ve spoken with Wendy Carlos, you will nearly always solicit that quiet look of disbelief.

Apart from isolated interviews in 2003 and 2007, the OG (“original godmother”) of electronic music has made good on perfecting the mien of a recluse. Here, then, is one of Wendy Carlos’ last interviews, appearing here for the very first time.

Before this project, you’d taken an extended break from releasing new material…

“Some people didn’t notice, and some people did. I put out the Telarc record [‘Switched-On Bach 2000’] in 1992. That was the anniversary project for ‘Switched-On Bach’, with some new things as well. A whole new set of performances. And then right after that I got involved with Larry Fast, another synthesiser specialist, and we were developing a technique for restoring films.

“We’re both film collectors and have large stacks of LaserDiscs and tapes. We were getting annoyed that a lot of films had grim sound. They’d fix the picture, but the sound is kind of poor. The ones that came before 1980 were mostly in mono, and we figured out a way to put them into stereo with a digital audio workstation.

“It was kind of a neat job. We developed this thing, and we were entrepreneurs. We sent out brochures and spoke to a lot of people, but nobody wrote back, and we really didn’t know what to do with it. So I guess you might say that we wasted two years, but the techniques we came up with are very useful for my own stuff, and for his stuff, too. But it was kind of a cul-de-sac. Then I got into a project with a few other people that eventually spun off into ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’, and that’s really been about three years.”

From start to finish, how long did ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’ take?

“Do you count embryonic projects? I’ve got a lot of things that I start that will probably still yet go into another recording, but they didn’t make it into this. They may have led to the path, but then I came up with ‘Clockwork Black’, which was the first big part of this that I started on.”

What was the draw for you as a composer to return to the ‘Clockwork’ themes?

“It wasn’t a draw originally. Some friends had told me that ‘A Clockwork Orange’ is a film that’s taken over from ‘Rocky Horror’ in college communities for midnight showings. Obviously no one else would have the right to go and tamper with that, because I was involved with the music. I did large chunks of the film. And the project suggestion was, ‘Could you do something that people in their 20s might enjoy?’. So I played, and I did it with fear and trembling. I didn’t remember it, because I hadn’t listened to it in a couple of decades. It sounded better than I thought. It wasn’t so awful. It wasn’t a painful thing. It was like, ‘Gee, I remember this!’. And as I played it, it began suggesting that we’d come enough years that some things from the late 20th century that were predicted by that film have come to pass. In some ways, our world is as grim and nasty as Kubrick tried to make it in the movie and Burgess’ wonderful novel had done in print.”

I paid a decent price for a vinyl copy of the soundtrack…

“My goodness.”

But I guess the CD is going to be released soon?

“We decided to get ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’ out first.”

What do you remember about working with Kubrick during the process of the film?

“Since he’s sort of reclusive, a lot of people ask me about him. I didn’t find him reclusive at all. He seemed extremely open, candid and bright. And very curious. He would ask questions to the point where you would just say, ‘Let me get back to my hotel room!’. He really was just fascinated about everything. I would be popping off questions about ‘2001’, and he was not shy at all. He would tell me anything I wanted to know. And he wanted to know how I do this, and what technology I used for that, and it was kind of funny how we drove each other into the wall with questions. He was open. He still had a New York twang. He didn’t sound like anyone from London [laughs].

“He was high strung and neurotic [laughs], but I could deal with that. He was rather rigid in a lot of ways. He would get locked into his temporary scores, and it was lucky that he heard a lot of our music early on, because he didn’t budge very far from what he had gotten used to in the editing room, playing them so many times he couldn’t bear to part with them. Even though it was just originally there as a place marker. So you found yourself having to kind of duplicate the place markers rather more literally than you would expect, just to maintain an ability to do the new cues. A lot of them he backed up on and went back to the originals, which is what happened with Alex North and the ‘2001’ score. But he’s not the only one. A lot of directors get locked into their temp scores.”

Had the idea crossed your mind to reconnect now that he’s back and producing another major film?

“So they say. It’s been in progress a very long time. I popped him off a friendly letter a couple of years ago, but I haven’t heard from him. When he’s in the middle of a film, you’re not going to hear from him anyway.”

Have you noticed any changes in your methods of composition?

“To me, it all seems part of a whole. I don’t know how people will eventually summarise the periods of my career like they do with everyone. They talk about early Beatles, mid-Beatles, and late-Beatles, so I guess that’s true for everyone. As a composer, I think I’ve gotten more secure. At times, in my youth, I used to think, ‘Gee, I can’t use too much of this idea because I’ll never have another great idea like that again’. You don’t realise that you have to throw the best things away in order to have more. That’s a human thing that you learn in life. I never run out of ideas now. It’s a lovely experience. I don’t know if that will always be.

“Aaron Copland, when I met him in the later years of his life, said that he finally felt he’d written himself out. He stopped composing. He was a fine composer, but that’s what he said in his late 80s. I don’t feel that happening to me. I’m really looking forward to opportunities to work with other people because it’s solitary. I’m stereotyped as being an electronic composer when I’m just a composer. I learned to write for piano, violin and orchestra, and now the synthesiser has finally grown up enough that it has about as much colour as an orchestra. Maybe more. But for a lot of years, it was like chamber music. It had a limited palette. The Moog synthesiser could go from A to G… or maybe to H. It couldn’t go all the way to Z in possibilities.

“The machines have gotten more expressive, and the technology has gotten a little more sophisticated in what you can get to control. They’re not nearly as flaky as the old machines. They haven’t moved anywhere near fast enough for me. There’s a lot of things that I’m dying for, but maybe they won’t happen before I die. I wish they would move in those directions, but they have to move in the ways that they can sell equipment.”

There are a lot people doing exciting things with electronic music as we approach the millennium. It seems like the market and the industry are responding?

“The industry is responding very well and it’s all very healthy. I think that having it in the hands of the average person is very healthy. It may indeed help most people who weren’t lucky enough to grow up as I did when there was a piano in every other house or every third house. That doesn’t seem to be the case anymore. But there might be some kind of a MIDI thing and a computer that can make music. It’s good that the public get more sophisticated, because then they will begin to demand more from their music than just the ‘dunka chunka dunka chunka’ that’s been going on for so many decades now.

“I’m beginning to wonder if everybody’s had a lobotomy. I am, as an artist, personally bored with most of everything that’s out there. It’s so baby-simple and so spoon-fed. It’s great to come across something that occasionally seem interesting. I have friends who bring me things to hear. They keep my finger in the mainstream enough to see what’s happening.

“‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’ was aimed at 20-somethings – it was an attempt I made that wasn’t in any way classical, but used classical techniques to come up with big gestures like an opera might do. Bigger than life, which a simple rock song cannot support. Yet I put in enough rhythm and melodrama that young people enjoy, so that it shouldn’t be off-putting and might actually make you want to hear more like that. That was the idea of it, and I can’t tell you if I succeeded or failed. I have no idea.”

Are there any new artists you’ve found who are interesting?

“I had caught on to some people before, but unfortunately they turned out to be fakers, so I’m not going to mention their names. There were some people who had some stuff, and I was responding to it, but then I discovered they had actually sampled some really good stuff. Even my friend Larry Fast had some things stolen from him. Then it’s like, ‘Gee, if everyone is just doing collage now…’, it becomes like this article I read – apparently, there’s so much stealing going on now that when you’ve tracked down a sample, it can be two or three steps down the road before the original person who created that sound is found. And that’s getting daffy. It’s just a silly position to be in.

“Collage is always a fun thing, but it isn’t a very deep form of art. You have to get into creating the things yourself. It’s like someone who learns to draw. If you really want to have a human form, you can cut an illustration out of a magazine with a pair of scissors and paste it on a piece of paper, and put some magic marker around it. But it’s better if you know how to draw a human form yourself. So I’m hoping that people will jump into the music world and learn to make music. It’s really not that hard. It just takes a few years. But surely it’s worth it, for an art form.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

It’s probably just the immediacy of the technology…

“It is. They think they can get away with it, and they don’t have to know, and in the end their ignorance will catch up with them. They’ll be very limited, like Vangelis. He never taught himself how to read or write music, and his music after the first few records sounds very confined. It’s claustrophobic. It’s the music made by somebody who doesn’t get out of the box.

“I feel like the opposite is true of what he used to say, where he was afraid that learning would wash away his originality. If your originality is that timid, then you don’t have much anyway. And that really knowing how to do things, like constructing something with a saw and a drill and hammer, the more you know, the better you are. I find life to be a constant learning process. I’ve never stopped learning. And if my music is different now, it’s because of all that I’ve learned.

“You get to be a little more of a human being as you get older and that shows in your music as well. It’s all part of the same thing. You can’t just be an artist, you have to be a human being first. And I’ve had friends of mine that who are rather tight-assed about this, they really get angry with me when I say that, ‘Well, I’m an artist first!’. Well, then your music is going to suffer! It’s really kind of frightening to me. Because it seems to me that what I’m saying isn’t provocative at all. It’s the obvious thing. I don’t think that what I’ve done in my music is anything but obvious, either. It’s what you’re doing with these tools. In the end I’m just a single artist sitting here in Manhattan, just trying to express my ideas as best I can.”

What’s next then for you?

“The re-releases are here and it’s fun to hear the old things. It was fun to restore ‘Timesteps’, and get it to sound good. But I am committed by the end of this year to get into another project, something to do with looking back at the past, at the millennium. And I want to do it. I’ve got a lot of notes, but right now I’m going to keep pushing the re-releases out. It’s a one-time thing, but it’s something I’ve got to oversee. It’s a very intense amount of work. But they’ll all be under one roof and I can supervise it.

“I want to get together more of the material that didn’t make it onto ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’, and a little more optimistic stuff as well. I’ve got a lot of things going on, but I want to see first if I can find the right approach to get a younger audience interested in what I do, because they’re the hope for the future. They’re going to be the next synthesiser players, and hopefully they will take the medium in a direction that’s healthy for us.

“So I’m looking forward to that. I really am. I’d love to be more involved with performing. We did a thing last year at the Beacon Theater, which was only Bach, because that’s the way the project was sold. But it was fun to be involved with a lot of people on stage. I’m aware now that if you can get the backing from someone who can mount a campaign to do something, we could even go onstage with ‘Tales Of Heaven And Hell’, with not too many musicians, and perform a great deal of that live. It’s something that I wouldn’t have been able to say a few years ago. And I’m a bit of a ham, so I would enjoy that.”