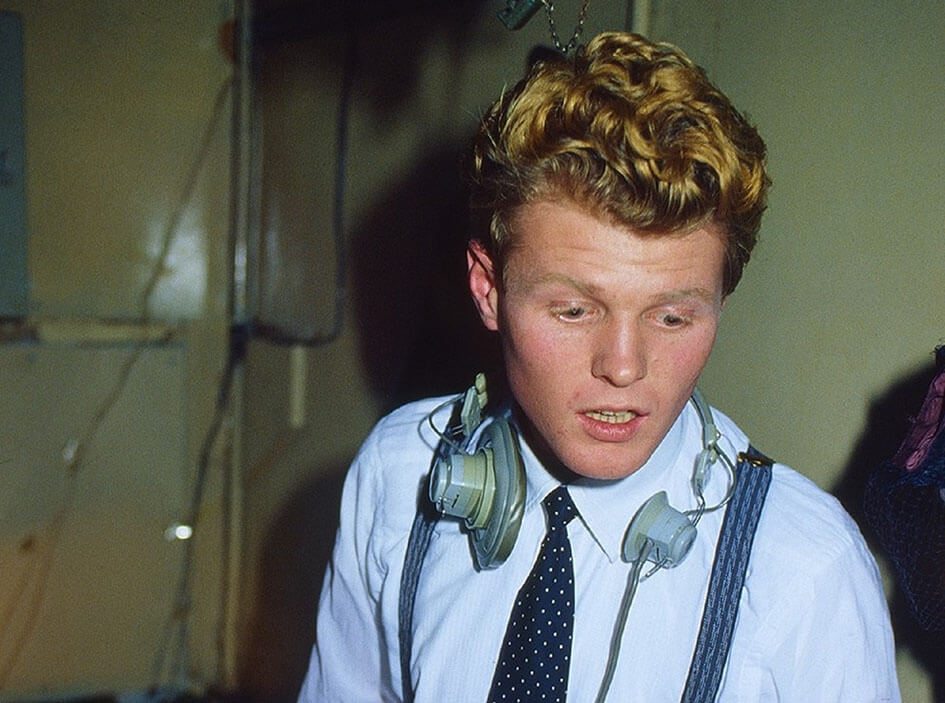

Stationed behind the decks, Rusty Egan made the Blitz club tick and was pivotal to the electronic and new romantic cause. With a definitive Blitz boxset incoming – curated by the man himself – he regales us with colourful tales of Kraftwerk, globetrotting and his late-career rebirth

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here