As ‘Blade Runner 2049’ hits cinema screens, the news that the film’s soundtrack composer Jóhann Jóhannsson has been replaced at the 11th hour by Hans Zimmer comes with a sense of déjà vu. Like a time warping Philip K Dick short story, didn’t all this happen before? It certainly did…

It was just another commission in Hollywood for film music composer David Rose. Born in London but raised in Chicago, Rose had been scoring Hollywood films for over a decade when, in 1955, MGM asked him to compose the music for their sci-fi movie ‘Forbidden Planet’, due for release the following year. He came up with an orchestral score, with some electronic noises included, and the main theme was in the can by the end of March. However, over the Christmas break of 1955, MGM’s president, Dore Schary, visited a club in Greenwich Village, New York City, and there he encountered Louis and Bebe Barron. He was so impressed by what he saw that he hired them to provide the music for ‘Forbidden Planet’. In what must have made a pretty miserable Christmas present, David Rose was fired while Schary was still on holiday. Schary himself was ousted from his position a few months later, which might have given Rose some cold comfort.

Louis and Bebe Barron were music graduates with an intense interest in creating electronic sound. They were based in Greenwich Village, which was an epicentre of creativity, especially in the avant-garde art and music scenes. They’d recently got married and had received a present, a tape recorder, from a cousin of Louis’ who was a senior executive at the Minnesota Mining And Manufacturing Company, aka 3M. It doesn’t sound like much these days, but the tape machine was a rare and magical machine in the late 1940s. Invented in Germany in the 1930s, it had been kept under wraps by Hitler’s government, aware as they were that it could be something of a secret weapon. After the war the technology was seized by the American forces and developed in the USA in the 1940s. Crooner Bing Crosby’s enthusiasm for tape led to him investing heavily in the then tiny Ampex company, and by the early 1950s tape machines had revolutionised the entertainment industry.

But in the late 1940s, the Barrons’ private studio, opposite what was then the Whitney Museum Of American Art, was home to perhaps the only tape recorder in the city. The studio was filled with electronic equipment that the Barrons had built themselves, inspired by the book ‘Cybernetics’ by the mathematician and philosopher Norbert Wiener, a hugely influential academic work about “the scientific study of control and communication in the animal and the machine”. The Barrons built circuits that would self-destruct, oscillators and all manner of weird and wonderful electronic sound creation and shaping devices which they described as having their own personalities, like characters in a script, as they put it, with their own life cycles.

They created the first piece of electronic music composed for tape in America, called ‘Heavenly Menagerie’, and worked with John Cage on ‘Williams Mix’, a piece commissioned by the African-American architect Paul Williams, who was part of the team who designed the Los Angeles Airport space age Theme Building.

Visitors to their cramped studio included Stockhausen, Boulez, Edgard Varèse (“He hung out there a lot,” Bebe Barron remembered in an interview in 1997, “he was so interested, and he had no equipment of his own…”). There were, as Bebe said, “no rules, no history” when it came to electronic and tape music, and they scored music for dozens of avant-garde films and dance performances, often allowing the circuits to create the sounds and pitches themselves without interfering with them, and then compiling tape recordings of the sounds into finished pieces.

But avant-garde didn’t always pay the rent, so the ‘Forbidden Planet’ commission was very welcome. The score was a triumph, MGM were delighted with it, but neither the Barrons nor MGM had accounted for the Musician’s Union. They weren’t members, and had created the music without musicians, so they couldn’t be credited as composers. The credit they received in the film was for “electronic tonalities”. They were prevented from being nominated for an Academy Award and a soundtrack album wasn’t released until 1976, when the Barrons put it out under their own steam in a limited edition, which they numbered and signed themselves.

Rose, meanwhile, destroyed his score with the exception of the main theme, which was released as single by MGM around the time of the film’s release. A couple of years later he wrote ‘The Stripper’ (yes, that one, with the trombones), and went on to enjoy household ubiquity with his theme tunes for the TV shows ‘Bonanza’, ‘The High Chaparral’ and ‘Little House On The Prairie’, which bagged him two Emmys.

Louis and Bebe Barron’s soundtrack for ‘Forbidden Planet’ represents a moment when the New York avant-garde and mainstream entertainment collided with spectacular results. It was the first all-electronic film score, and set the tone for many future sci-fi film and TV shows, not least the work of the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, which was set up just a couple of years after ‘Forbidden Planet’ was released.

The gravestone of composer György Ligeti, who was 83 when he died in 2006 is an impressive modernist monument, a large slab of glass with his name engraved into it. It was designed by the Vienna-based architects and designers Bulant & Wailzer, and its conceptual resemblance to the iconic black obelisk from the film ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is striking. Ligteti’s music is well-known to most people because of its use in Kubrick’s masterpiece, perhaps the best science fiction film ever made. But Ligeti was “shocked and appalled” when he saw the film for the first time. He wasn’t the only composer who felt that way on seeing the film. Alex North, one of the most revered film soundtrack composers of the day, first saw the film at the premiere in New York City, shortly before its general release. Ligeti’s shock was because his music was all over the film, but without his permission, North’s because the music he’d been commissioned to compose and record for the film – over 40 minutes of it – was nowhere to be heard. Kubrick had junked the lot.

To say that the story behind the score of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ is convoluted, disputed and so utterly obscured by both secrecy and conflicting reports is an understatement.

Alex North had scored Kubrick’s blockbuster ‘Spartacus’ in 1960, and had 10 Oscar nominations under his belt by the time Kubrick engaged him for ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’. The recording sessions started in London in January 1968, just four months before the film’s release. But the film had been in production since the end of 1965, and Kubrick had been trying all kinds of music on rough cuts of scenes, including pieces by Johann Strauss II, Richard Strauss, Chopin, Schumann, Carl Orff and, according to several sources, Ligeti. In fact, in February 1968, Ligeti wrote to a friend saying that his music publisher was negotiating with MGM for the use of his piece ‘Requiem’.

Kubrick also hired composer Gerard Schurmann in 1967, apparently as a standby composer and music consultant. When Schurmann heard that Alex North had been hired, he assumed, correctly, that his involvement with the film was at an end. During his tenure, he and Kubrick had already discussed Ligeti’s piece ‘Atmosphères’ at length, which ended up as the first music heard in the film. Schurmann later received a message from Kubrick thanking him for his input and asking him to put in an invoice for his time. “I declined to name a price in the hope that he would perhaps remember me for a future project,” Schurmann told Paul Merkely of The Journal Of Film Music in, yes, 2001, “no such luck!”.

One theory put forward for this mess was that Kubrick was keen on keeping the temporary music he’d placed against his film, but that the studio, MGM, wanted an original score. A major MGM movie had to have a sense of occasion about it, and an original score was an essential part of that. North later recounted that Kubrick was “direct and honest” about wanting to keep some of the “temporary” music, but North wouldn’t contemplate the idea of composing a score interspersed with pre-existing recorded music. By the end of January, North was off the project. The most plausible explanation is that North was hired because obtaining clearances for the music of Ligeti and the others was proving too difficult. Certainly, that’s what North’s wife, Anna Höllger-North said in 1998: “All along he [Kubrick] was trying to clear the rights to the temp track music so he really under pretext had Alex compose the score. Kubrick managed to clear the rights and Alex was never told that.”

Ligeti later said he didn’t know anything about his music’s role in Kubrick’s masterpiece until a friend from the States contacted him and urged him to go and see it as soon as possible and check out the music. He went to see the film’s opening in Vienna, the city he called home after fleeing Hungary following the Soviet Union’s crushing of the uprising there in 1956. “I was absolutely astonished,” he told The Guardian in 1974, “I became very angry.” He went a second time with a stopwatch, and discovered that no less than 30 minutes of his music had been used. He kicked up a stink and was eventually paid a $3,000 fee and royalties.

Ligeti actually loved the film’s use of his music: “I found the way in which my music was used wonderful,” he told the German newspaper Die Welt in, yup, you guessed it again, 2001. “It was less wonderful that I was neither asked nor paid.”

Alex North was, eventually, phlegmatic about the experience. “Well, what I can I say? It was a great, frustrating experience,” he said when reflecting on it some years later. Another composer, Henry Brant, who worked with North on the score and had conducted the orchestra during the recording sessions later remembered that Kubrick had listened to North’s score and said, “It’s a marvellous piece of music, a beautiful piece, but it doesn’t suit my picture”. Kubrick himself, in an interview with French film critic Michel Ciment several years after ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, was more blunt: “He [North] wrote and recorded a score which could not have been more alien to the music we had listened to, and much more serious than that, a score which, in my opinion, was completely inadequate for the film.”

North’s rejected 1968 recordings eventually saw the light of day in 2007 via a CD release, and in 2014 a spectacular ‘Beyond The Infinite’ coloured vinyl edition, limited to 2001 copies, was released by Mondo.

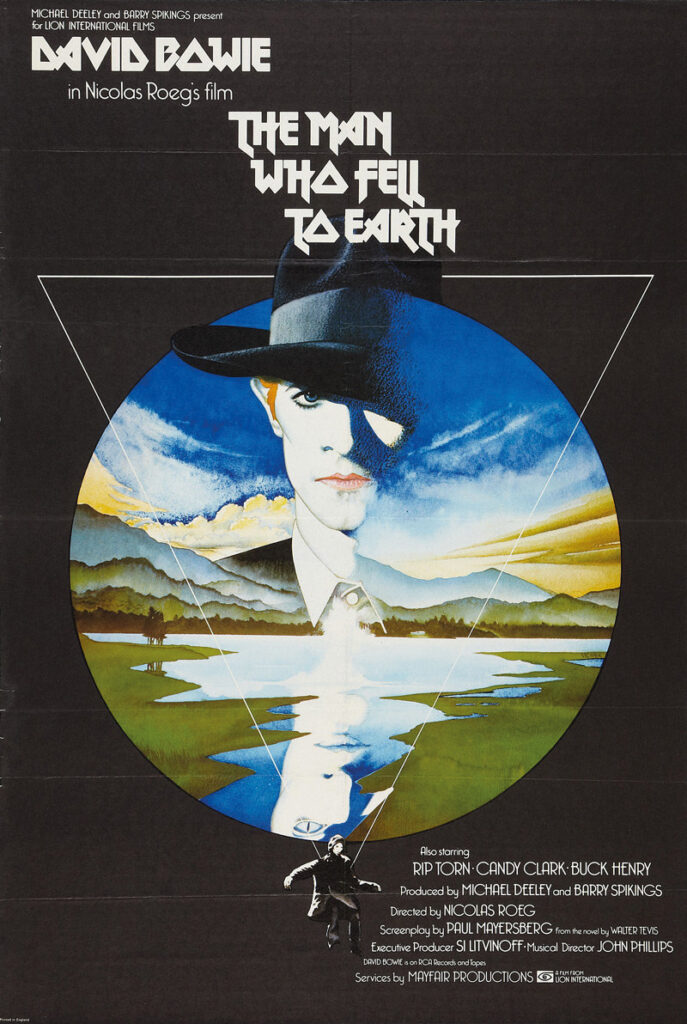

Fast forward past ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, past Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971) with its groundbreaking electronic music contributions from Wendy Carlos, past Nicolas Roeg’s ’The Man Who Fell To Earth’ (1976), which Bowie thought he was scoring, but ended up being completed by John Phillips of The Mamas & The Papas and Japanese percussionist Stomu Yamash’ta in a chaos-filled frenzy (which was finally released last year, 30 years after it was made), and we arrive at 1982, and the cinema event which we’re now probably going to have call the original ‘Blade Runner’ film.

Director Ridley Scott was riding high after his 1979 sci-fi hit ‘Alien’, and the composer he chose to work with was Vangelis, who had recently scored Hugh Hudson’s hit ‘Chariots Of Fire’. The choice of Vangelis was inspired. An all-electronic soundtrack from a composer at home working with orchestral concepts and able to create unusually emotional music from machines was the perfect musical motif for the theme of the film; machines with emotions.

Vangelis used his arsenal of synths to forge an unforgettable sonic backdrop for Scott’s extraordinary vision of Los Angeles, 2019. As the credits rolled in the cinemas, newly minted hardcore ‘Blade Runner’ fans who waited patiently were rewarded with the news that the soundtrack was due for release by Polydor Records. But eager visits to record shops drew a blank. There was no soundtrack album, not on Polydor or any label.

What did get released in 1982, via WEA’s Full Moon imprint, was an album cunningly titled ’Blade Runner (Orchestral Adaptation Of Music Composed For The Motion Picture By Vangelis)’ by the New American Orchestra. With all the requisite sleeve artwork in place to identify it as a bona fide soundtrack release, including Vangelis’ name (‘Inspired By…’), it sold in droves to people who must have wanted to throw it out of the window, after one listen revealed it to be a cynical knock-off that barely resembled what they had heard in the cinema. It was perhaps worse than the ‘Top Of The Pops’ albums of the 1970s which featured studio musicians replicating the hits of the day. Some 12 years later, a version was released which, while far better than the 1982 abomination, still fell short of fans’ expectations.

The details of the dispute which held up the soundtrack’s proper release for so long remain unclear. When the comprehensive three-disc version finally saw the light of day in 2007 (the 25th anniversary of the film’s release), all Vangelis could offer by way of explanation for the years of purgatory for the ‘Blade Runner’ soundtrack was, “I do not wish to dwell on this subject; suffice to say it was not a particularly happy situation for me.”

The most likely explanation is as mundane as many other Hollywood stories. The studio wanted to rush out a soundtrack album as quickly and cheaply as possible. Vangelis, a serious composer and not a hack, wanted to time to work on the short pieces and cues he had put together for the film in order to produce a fully realised album that could stand on its own merit and would be worthy of his name. The studio refused to entertain the idea and sanctioned the release of the muzak version of Vangelis’ work instead. Vangelis was, to say the least, not pleased. As it turned out, the film didn’t actually do that well on its initial release at the box office and so Vangelis, although slighted, moved on. It wasn’t until the project’s cult status grew in stature sufficiently that a Vangelis-approved release of the music was deemed worthwhile.

Still, 35 years later, and surely there would be no chance of some kind of controversy attaching itself to the Ridley Scott-produced Denis Villeneuve-directed sequel, ‘Blade Runner 2049’ soundtrack, would there? Well…

No one was hugely surprised when Vangelis wasn’t retained to score the film, though some disappointment was expressed by the legions of ‘Blade Runner’ aficionados, whose ranks have swollen considerably thanks to the reissues of Scott’s various versions and, of course, the internet. But they were mollified by the announcement that Iceland’s Jóhann Jóhannsson had been secured for music duties and that the spirit of Vangelis’ work would guide him.

Jóhannsson was well-respected for his atmospheric and inventive scores for Denis Villeneuve’s previous two films, ‘Sicario’ and the literate sci-fi hit ‘Arrival’. His background as an electronic musician, with his Kraftwerk-influenced band Apparat Organ Quartet, and his artful man/machine neo-classical solo work seemed to make him the perfect inheritor of the considerable Vangelis mantle.

“I have been working on it for quite some months already,” he told me when I spoke to him earlier this year. “I always start very early, before filming starts, usually. But that doesn’t mean that I’m working on it every day, it just means that I’m doing research and looking for material, recording material and trying out ideas. Sending ideas to [director] Denis Villeneuve, starting a discussion, you know? But we start the music discussion very early on.”

He’d signed the usual non-disclosure agreements about his work on ‘Blade Runner 2049’, but was open about his reverence for Vangelis’ original score.

“He is a composer that I admire tremendously,” he said, “and someone who has been an influence on what I do even though you might not hear it in an obvious way. But what I love about the way he works is that he likes simple, strong statements. You know, melodic? And simple, strong motifs. And that’s something that I love as well. And he uses space, or atmosphere, very well. And he somehow manages to make things sound big and epic with just a few synthesisers and sequencers and has managed to create a sound that’s totally his own.”

He was well aware of the film’s legacy, and the risks associated with the sequel.

“You have to basically try your best not to mess it up,” he told me.

So when it was announced that Hans Zimmer and his protégé Benjamin Wallfisch would be “joining” Jóhannsson in scoring the film, the writing was on the wall. To most Hollywood observers, it seemed deeply unlikely that Hans Zimmer, the don of contemporary high budget film scoring, would share duties with a name like Jóhannsson. And sure enough, just weeks before the film’s release, the news came that Jóhannsson was off the project entirely. We’ll probably never know the full story of the Jóhannsson soundtrack for ‘Blade Runner 2049’, Hollywood NDAs are airtight and draconian these days. We asked his management for a statement, to which they replied that they are “legally restricted to talk about the movie”. In an industry where composers can find themselves out of work for speaking out of turn, no one’s talking.

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

Perhaps Jóhannsson’s background as a European artist, rather than a fully committed Hollywood guy stood against him. Maybe the sheer scale of this production delivered the kind of studio pressures and interference that Villenueve was able to resist with smaller films like ‘Sicario’, but couldn’t hold back this time. Even ‘Arrival’, with its eye-waveringly huge-sounding budget of $47 million is dwarfed by ‘Blade Runner 2049’, with a budget looking more like a staggering $250 million. With that kind of money at stake, all manner of interests are going to have a say in how it turns out, and if they feel that a score is not commercial enough, or too arty, too damn weird, or that what they’re asking for isn’t forthcoming because the composer is too opinionated and is pursuing his own creative vision, well, that composer might get the boot. Alex North thought he was delivering exactly what Kubrick wanted 50 years ago, but it turned out he was wrong. Perhaps Jóhannsson succumbed in a similar manner.

It’s all a long way from the electronic tonalities of Louis and Bebe Barron back in 1956, but somehow the echoes of that first act can be heard in this final reel, too.

Perhaps the last word should go, surprisingly, to Gary Numan. Numan left England for Los Angeles a couple of years ago. Part of the plan was to get into film composing.

“I chatted to friends who compose for films,” he says. “We talked about the ups and down of composing for films, the workload and the deadlines, and the money you get from it. If you start getting into bigger budget films, a committee will turn up at the studio, none of whom like each other, they’re all arguing and want to put different things on it. ‘We don’t want a string orchestra now, we want a triangle’. Oh, do you? You get caught in the middle of all these ego battles, they disagree with each other because of their own problems with agreeing with each other. And you’re the composer in the middle of all this, trying to sort it all out, and you have to go back and undo everything you’ve done and try to figure out what was the middle ground that all these people were saying. Sod that. I can’t be bothered.”