How does ‘The Man-Machine’, Kraftwerk’s vision of the future, hold up after four decades? We compare and contrast the vision of 1978 with the reality of 2018

‘The Robots’

1978

Robots in 1978 were, as they are now, all the rage. R2-D2 and C-3PO, the Laurel and Hardy double act of the ‘Star Wars’ film a year earlier, were the most famous robots on the planet.

But Kraftwerk had nailed the first problem that might face robots wanting to roam around doing as they please: battery life. The first line of the first song on Kraftwerk’s robot record addresses the issue (‘We’re charging now our battery’). By the end of the song, the robot is telling us that he and his metal pals “…are programmed just to do/anything you want us to”.

And in 1978, in the real world, that was exactly what was happening, thanks to the invention of the PUMA (Programmable Universal Machine for Assembly) robotic arm. It was introduced by Unimation, the world’s first robotics company. They’d developed the first robotic arm back in 1961, and it was used by General Motors on assembly lines, but the 1978 PUMA was a great leap forward. It had been developed by Victor Scheinman who had his own robotics company until Unimation bought it. Thanks to the PUMA, as the 1980s got under way, robots became ubiquitous in car factories, automated assembly lines made unimaginable efficiencies possible, and put thousands out of work. But they didn’t look like proper robots, did they?

2018

As we look around our Facebook feeds in 2018, evidence of the rise of the robots comes thick and fast in videos going viral from robotics labs all over the world. You’ve seen the one with the four-legged robot opening to door to let itself out, right? Combined with artificial intelligence, and the ability to run through the woods (you’ve seen that one, too, right? And the one with the robot jumping and doing mid-air flips). Boston Dynamics, a company which started as spin-off from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have been making a big noise with their videos of robot stress tests (it’s their SpotMini bot that can open doors), and they’re certainly delivering on their company mission statement, “Changing your idea of what robots can do…”.

Elsewhere, at the 2018 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, several new domestic robots were unveiled. The Aeolus Robot can hoover and mop floors, and recognise 1,000 household items and pick them up and put them away with its agile arm. Ubtech Robotics’ Walker robot can stroll around your property like a security guard. It can also play music, dance and do all kind of tasks via voice commands, like emailing and video conferencing.

Honda, whose ASIMO robot first hit the headlines in 2000, has a new 3E range of robots (the three Es are Empower, Experience and Empathy) including the A18 which shows empathy with a variety of facial expressions. And inevitably, the Californian RealDoll company is developing sex robots. They’re close enough to developing a commercial model for there to be a bona fide Campaign Against Sex Robots (campaignagainstsexrobots.org).

‘Spacelab’

1978

Kraftwerk generally avoided the star-gazing of their kosmische counterparts over in Berlin, but it did creep into proceedings once or twice in the 1970s (they were pretty interested in comets in 1974), and here we have their celebration of Spacelab. Wait, what’s that? Spacelab? There was no Spacelab! There was a Skylab, the American space station which orbited the Earth between 1973 and 1979. But now you mention it, Ralf, Spacelab would have been a better name for the science lab in space, or, as NASA preferred to call it, their Orbital Workshop.

The final trio of astronauts to crew Skylab, from November 1973 to February 1974 sound like the crew of John Carpenter’s dark space comedy ‘Dark Star’. Two of them were badly space sick, but decided to keep it a secret from Mission Control, without realising that Mission Control could (and did) download and listen to recordings of all their conversations. The crew later decided that being asked to work 16 hours a day without a day off was a bit much, and went on strike. They turned off the communication channels and kicked back for a day. In December, they photographed Comet Kohoutek, the same one that inspired Ralf and Florian to pen a couple of versions of ’Kometenmelodie’ and ‘Kohoutek-Kometenmelodie’.

In 1978, as Kraftwerk carefully enunciated ‘Spacelab’ into a vocoder down below in Düsseldorf, NASA noticed that the by-now empty Skylab’s orbit was “decaying”, or in plain English, it was about to plunge to Earth. In July 1979 it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere and broke into pieces which landed in both the Indian Ocean and western Australia. Today, chunks of Skylab can be seen in low-rent museums in the Australian outback.

2018

After Skylab, the Russians launched MIR, then there was the International Space Station, which pretends to be Father Christmas’ sleigh once a year. In 2011, China put Tiangong-1 into space and by the time you read this, it should have re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere and broken up, according to the report the Chinese gave to United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Tiangong-2 launched in 2016.

But the space headlines in 2018 belong to Elon Musk, the man with the comedy billionaire comic strip character name, whose fantastic wealth is funding his SpaceX company and their long-term ambition to colonise Mars. Falcon Heavy was launched in February, with a Tesla car on board, and a dummy called Starman (after the Bowie song) in a spacesuit driving it, while ‘Space Oddity’ played on the car stereo. Reality has outstripped both fiction and Kraftwerk’s observation of the race for space in this peculiar 21st century we find ourselves in.

‘Metropolis’

1978

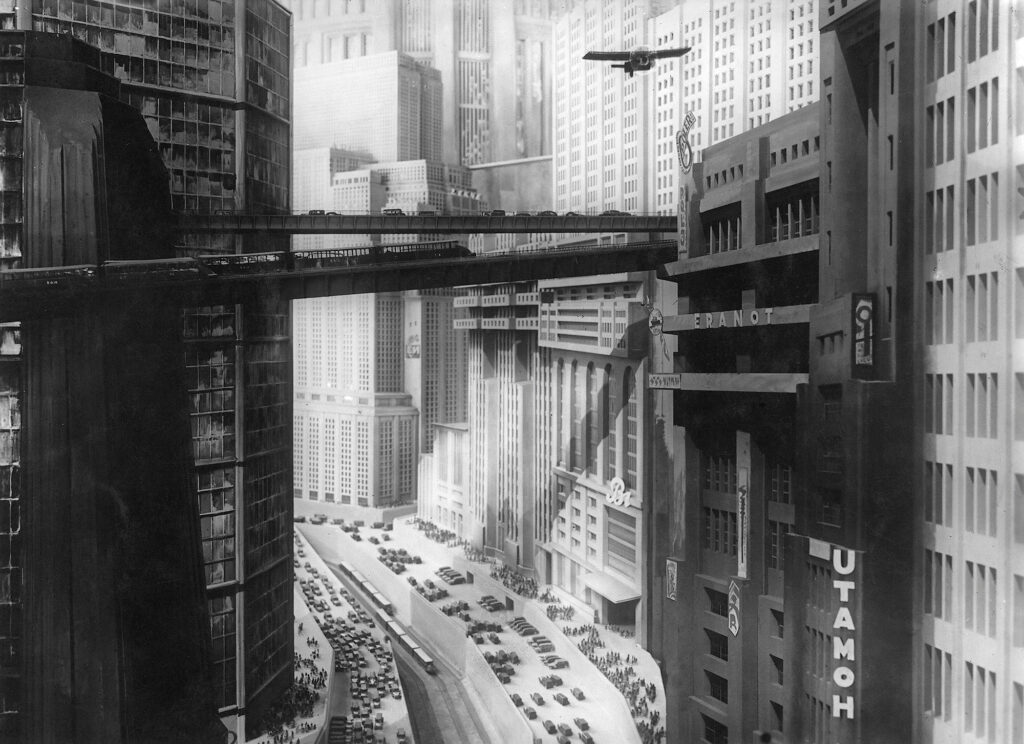

It’s not specified whether the Kraftwerk lyric (if you call repeating the word ‘Metropolis’ six times a lyric) is about the 1927 Fritz Lang film which tackled the de-humanising impact of industrialisation on the human soul, or whether it’s a wider attempt to evoke the idea of a city.

Received wisdom is that it’s inspired by the film, which is rather cemented by the fact the film played on a loop during press launch of the album in Paris in April 1978. The driving nature of the song and its unresolved melodic tension certainly seems to suggest the edgy and energetic throb of a large city. It works either way; the film was about a future dystopian city, powered by a “Heart Machine”, giant clocks beating out time, and the same ideas could be applied to any modern metropolis, Lang’s prescient vision holds to this day.

2018

Fritz Lang’s film was set in 2026, unimaginably far into the future for him (100 years), and nearly 50 years for Kraftwerk. The film went on to have its own decidedly messy life-cycle. On release, ‘Metropolis’ received mixed reviews, bombed at the box office and was cut from nearly three hours long to a more manageable 80 minutes, which rendered it incomprehensible. The missing scenes were thought to be lost forever, but in 2010 a full-length version was released, put together from a print discovered in an archive in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and another found in New Zealand.

‘Metropolis’ has been re-scored multiple times. In 1975, the BBC screened the film as part of their Tuesday Cinema season and commissioned an electronic score from William Fitzwater and Hugh Davies, a student of Stockhausen in the 1960s, for the occasion. Giorgio Moroder famously scored a “colourised” version in 1984 with some clunkingly awful 1980s big hair pop with help from Freddie Mercury, Jon Anderson and Bonnie Tyler. Techno legend Jeff Mills scored it in 2000 and just last year, Factory Floor live scored the film. The six minutes Kraftwerk dedicated to it may well remain the best attempt to give the film a new sound.

‘The Model’

1978

‘The Model’ would have an impact on Kraftwerk themselves which they couldn’t have predicted at the time. As a lyric, it’s the first time the band acknowledged human desire, it represents their first foray in to the messy territory of boy/girl relationships.

At the time of ‘The Man-Machine’ album, ‘The Model’ (or rather the German version, ‘Das Model’) was released in Germany as a single, and didn’t even dent the UK charts. But when it was chucked on the B-side of ‘Computer Love’ in the UK in 1981, there followed a classic “DJs prefer the B-side” scenario. In response to the unexpected airplay, EMI rush-released ‘The Model’ as a single in its own right. Ralf and Florian’s displeasure at this turn of events may have been tempered somewhat when the record gave Kraftwerk their one and only UK Number One hit.

‘The Model’ can be read as a uniquely Kraftwerkian buttoned-up electronic version of The Beatles ‘I Saw Her Standing There’. Lennon and McCartney sang about seeing a girl across a dancefloor and the sweaty, ecstatic coming together of boy and girl. Kraftwerk’s encounter is much more adult, sophisticated and unfulfilled. Man sees model and wants to take her home.

But judging from the song’s final line, “Now she’s a big success/I want to meet her again”, our narrator’s relationship with the model was fleeting, she’s unreachable, she’s available only for the camera’s gaze (and for the money). It’s a cynical, decadent and detached world being described here. Where John and Paul’s environment for ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ is the Liverpool dance hall of the early 1960s, Ralf and Florian’s ‘The Model’ exists in the 1970s frozen glare of the catwalk flash bulb pop.

Did this breakthrough lead to the strange dislocated scenes of sexuality and mundane relationship hassles we witness on ‘Electric Café’, one of sex objects and telephone calls? ‘The Model’ aside, it seemed that Kraftwerk’s humanity was better received when it was cloaked in the obfuscation of theory and art, rather than confessional or observational of human weaknesses.

2018

It may well be that the unexpected success of the ‘The Model’ led to Kraftwerk’s most surprising album, ‘Electric Café’. We don’t know, of course, and it seems unlikely that either Ralf or Florian are ever going to discuss the creative process they went through together to create their back catalogue, but it doesn’t seem entirely preposterous to suppose that these intelligent and analytical artists would ask themselves why ‘The Model’ was such a huge hit, and their other singles weren’t. And it wouldn’t have needed an engineering genius to work out that it might have something to do with singing about sexual desire. In 2018, in the post-Weinstein era, the male gaze is under scrutiny like never before, and perhaps ‘The Model’ is a more problematic lyric these days, especially as there does exist a live recording that purports to be the band soundchecking this song, with the lyric changed from “Now she’s a big success/I’d like to meet her again” to “I want to fuck her again”.

‘Neon Lights’

1978

Kraftwerk’s beautiful electronic poem to the city at night is, for many, their high-water mark. The group had been in love with neon at least as far back as 1973, when Ralf and Florian had their names modelled in neon tubes and boxed in perspex.

Neon light itself was first demonstrated by the French inventor Georges Claude in Paris in 1910. There’s some disagreement among historians as to the first commercial use of neon lights, but within a few years, there were 160 neon signs lighting up Paris at night. There was a neon Cinzano logo on either the Champs Elysées or Boulevard Haussmann (depending on which account you read), and many Parisian emporia like the elegant and luxurious hairdressers Palace-Coiffeur and fashion and beauty salon Madame Caravaglios on Rue de la Paix were glowing glamorously with neon. The Pierre Lafitte publishing house chose neon to advertise its magazine titles on its Avenue de l’Opéra building.

Kraftwerk’s vision for ‘Neon Lights’ was chic and retro, existing in a dreamworld of a stylish Parisian era between art nouveau and art deco. When ‘Neon Lights’ was released as a 12-inch single in the UK, it was pressed on luminous vinyl which, like the neon-lit it fantasy it let you drift into, glowed in the dark. Perfect.

2018

Some 100 years after it started to dominate the cityscapes of Europe and the USA, and 40 years after Kraftwerk immortalised the romance of neon lights in song, the elderly technology is still going strong. Like the synthesisers in Kraftwerk though, digital is taking over. In 2014, a digital billboard eight stories high and as long as a football field was installed in New York’s Time Square on the Marriott Marquis hotel at 1535 Broadway. The rate for advertising on this massive marvel of telly tech? A mere $2.5 million for four weeks. The first advertiser was Google.

In November 2017, it was outdone by the arrival of the highest resolution screen seen on Times Square, the 8k beast was 91 feet high and 186 feet wide, that’s over 17,000 square feet, and wrapped around a corner plot at 20 Times Square, fronting a 39-story tower home to the Marriott Edition hotel. Impressive, but does it have the romance of the neon lights?

‘The Man-Machine’

1978

According to Kraftwerk , the Man-Machine is a “super human being”. If we’re talking upgraded humans in 1978, we’re talking the TV show ’The Six Million Dollar Man’, which was based on Martin Caidin’s 1972 novel ‘Cyborg’. After a cataclysmic accident during a test flight, astronaut/pilot Steve Austin is rebuilt in a lab to be better than a mere human. A bionic eye, arm and legs meant he could run like the clappers and see like an eagle. The show was cancelled in 1978 after a four-year run.

The idea of a Man-Machine in 1978 was an abiding trope in fiction, but they weren’t real. Cyborgs (cybernetic organisms) had first been mooted in 1960 by scientists Nathan S Cline and Manfred Kline in relation to developing a kind of human able to live and work in space and on other planets. By 1988, Hollywood had given us ‘The Terminator’ (Arnold Schwarzenegger played a T-800, the liquid metal dude in ‘Terminator 2: Judgement Day’ was a T-1000) and the Detroit copbot ‘RoboCop’, but they still weren’t a reality.

2018

I for one welcome our new cyborg overlords… In the 1990s, British scientist and university professor Kevin Warwick started experimenting with implants and could switch lights on and off by entering and leaving a room. In 2002, he had a more complex array of electrodes called BrainGate inserted into his left arm (the surgery took two hours) and was able to control a remote robotic arm with his own movements over the internet.

Other bionic enhancements that are on the verge of becoming widely used are replacement artificial kidneys, hearts, eyes, knees, elbows, pancreas, feet, cochlea implants, exoskeletons and even the hippocampus part of the brain, which is often damaged by stroke and Alzheimer’s and affects short-term memory. According to future-gazer Professor Yuval Noah Harari, a combination of artificial intelligence, gene therapy and automation is going give rise to a new kind of human, he calls them homo deus (god man), and predicts that homo sapiens (that’s us) may become an endangered species.

And if that seems too fanciful, consider Nissan’s recently announced brain-to-car interface. The car is a hybrid driverless/let-the-human-think-they’re-driving piece of tech. Using brain scanning sensors, the software (which appears to run on an iPad) can predict steering decisions that are about to be made by a driver. There’s a 300 millisecond window in which the software can help the steering process. “You feel like you are in control, driving perfectly on a winding road,” says Nissan Executive Vice President Daniele Schillaci. It’s all aimed at a more enjoyable “autonomous driving experience”. Nissan are preparing a vehicle that is ready for brain connectivity.

Humans who can afford it, all this seems to be telling us, will interface with computer algorithms and become better at everything. Once they become enhanced humans, the rest of us will be swinging on tyres hanging off ropes in glass enclosures and bidding for elderly analogue synthesisers on eBay.