One of the more curious arms of the Factory roster, there was never a dull moment with art punks Minny Pops. Lead man Wally Van Middendorp reminisces on the journey that started with a band called Tits

New York, 10 January 1981. The venue is the Peppermint Lounge and somewhere in the building is Suicide’s Alan Vega and Martin Rev. There’s a band on stage, the singer is tall, six foot six, and whip thin. He’s wearing a suit, has short hair and thick-lensed glasses. There’s a synthesiser player and a reel-to-reel tape machine is producing primitive drum beats and synchronised distorted synth lines. A guitarist creates bursts of thin noise, and a bass player keeps up a melodic rumble of mutant groove. The singer moves occasionally, his dancing is a series of sudden jerky collapses, like one of those toys held taut with elastic until you press a button in the base.

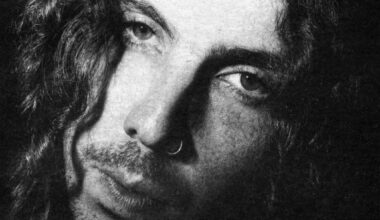

The singer is Wally Van Middendorp. The band is Minny Pops from Amsterdam, and they’ve just signed to Factory Records.

“I remember Alan Vega strutting around like a peacock in a leather jacket with diamonds on its back,” recalls Wally in the liner notes of the DVD that includes the above performance.

The Minny Pops story begins in Amsterdam in 1978, when Wally released his first record under the name – brace yourself – Tits. The seven-inch featured two tracks, ‘Daddy Is My Pusher’ and ‘We’re So Glad Elvis Is Dead’. The whole thing was a wheeze dreamed up by Wally and a friend who worked in an Amsterdam record shop after a rep from Phonogram asked if he knew of any bands worth checking out.

“On the spur of the moment,” says Wally, “we decided to do something and pitch it to Phonogram”.

Unsurprisingly Phonogram passed but true to the spirit of the age, they decided to release the record themselves. And so the Plurex label was born, which Wally continued to run throughout his tenure with Factory, putting out now highly sought after singles by the Dutch punk bands Filth and Mollesters and albums by well-regarded bands like the Netherlands’ answer to Talking Heads, The Tapes, and The Twinkeyz from Sacramento.

The Tits record is every bit as silly and cartoonish as it sounds, but somewhere in its erstaz punk boogie woogie madness is the evidence of the art prankster at the heart of it. And thanks to his brother attending the art school in Amsterdam, Van Middendorp was able to meet like-minded arty sorts and put together the first line-up of Minny Pops.

“The idea was that it would be a conceptual thing, three gigs and an EP and that would be it,” he explains. “We had an idea to play something that was electronic and minimalist, and to use repetition to push boundaries.”

At the time, Amsterdam was edgy. It was home to intersecting youth cultures, where the hippie hangover of the 1960s had hardened into a 1970s politically aware counterculture, intensified by the punk energy seeping across the North Sea from the UK. There’d already been serious rioting in 1975 when the city tried to demolish buildings to make way for the metro system. Many of the residents were squatters, and the animosity between them and the authorities was barely contained. Violence erupted again in 1980 when a crackdown on squatting was fiercely resisted.

“I remember there was a squatters’ building, and the army came in with tanks to evict them,” says Wally.

This was the febrile atmosphere that backdropped the development of Minny Pops and fed into their confrontational instincts. Everything about them was at odds with pretty much everything that was going on around them. They didn’t look like punks or hippies, their “singer” wore a suit and fixed the audience with an impassive gaze between songs while the band stood stock still, not playing for anything up to two minutes.

“We would have what I liked to call a ‘standstill’ between songs,” says Wally. “My thinking was that it wasn’t about the applause, it was about allowing the musicians on stage to reflect on their performance. Did we confuse audiences? Oh, very much.”

At one gig, which introduced a new guitarist to the line up, the new recruit was allowed to play just one song and was ordered to wear a white shirt, onto which a film was projected for the rest of the show. It was, Wally says, minimalist art.

“It was minimalist because of technology, there wasn’t much to programme with our drum machine. It was a Korg Mini Pops. It had an A rhythm or a B rhythm. It was about feeling uncomfortable and challenging the audience and not going into your standard gig performance,” he says.

You might also want to file Wally’s dancing style under the minimalist tag. He would occasionally bend at the waist, or throw his head back. It owed more to the performance art of Gilbert And George than anything that was going on in pop music at the time.

“I like to tell people I’m a great dancer, the Nureyev of electronic bands,” says Wally. If he’s joking, it’s hard to tell.

Minny Pops’ first album, released on the Plurex label in 1979, was an amalgam of spiky electronic art chaos, flat-out noise, rudimentary drum machine and no wave guitar backing monosyllabic, mechanical post-punk beat poetry. It was more in tune with the uptight amphetamine intensity of New York’s no wave scene than Factory’s nascent dark underground pop and left field dancefloor roster. And yet those two worlds would collide one night in Eindhoven.

“I had a few bands on my label from Eindhoven,” says Wally. “It was something of a creative hub, with the club De Effenaar at its centre. They were booking bands like Static from New York, OMD and Joy Division. We were offered the support slot on all Joy Division’s Netherlands dates, but we opted to take just two dates, The Hague and Eindhoven, on 18 January 1980. And that’s how we got into the Factory fold.”

As was par for the course back then, the Eindhoven gig nearly erupted into violence when it was crashed by a local motorbike gang.

“There was a lot of tension,” says Wally. “The local rockers turned up and there was a feeling that they were going cause trouble.”

The toughs marched into venue about 20 minutes into Joy Division’s set and paraded around shouting for a few minutes, but left without throwing a punch. There’s a recording of the show where you can pinpoint the moment the atmosphere changes, as the band starts ‘Dead Souls’.

“After the show,” recalls Wally, “we were in the dressing room and Rob Gretton said something like, ‘Would you like to come over to Manchester and release a record on Factory?’.”

The deal was done with the usual Factory attention to detail.

“Did we sign anything? No, of course not! The only official statement I ever got was a letter from Alan Erasmus, something about the record selling well and having to do a repress. The key line I remember was, ‘It’s not about the money, it’s about the fun of releasing the record’.”

The single was ‘Dolphin’s Spurt’ [fac 31] released in 1981. The song had already appeared on the 1979 album (as ‘Dolphins Spurt’, without the apostrophe), and again on a 1980 live seven-inch. The Factory version was recorded with Martin Hannett at Strawberry Studios in Stockport.

Minny Pops were relatively unusual on the Factory roster in that they already had some releases under their belts, and had their own label in Plurex. Were they anticipating great things as a result of signing?

“Stuff happened because of us signing to Factory,” says Wally. “We had a good run of dates in the UK with Joy Division, with New Order, we played with bands like the Au Pairs and ACR in London, had some great experiences, including a John Peel session, and a north American mini tour. We had adventures.”

One of those adventures was the legendary Joy Division Derby Hall show in Bury, which descended into a riot. Ian Curtis was too unwell to perform a whole show, and so it turned into a kind of Factory All-Stars event, with Crispy Ambulance’s Alan Hempsall depping for Curtis on a couple of songs and Section 25 joining them on stage. This was after Minny Pops had spent a happy 40 minutes antagonising the crowd with their “standstills” and minimalist weirdness.

“There was a faction in audience looking for trouble,” says Wally. “It was kind of a tense gig.”

There was another Minny Pops single on Factory, ‘Secret Story’ [FAC 57] in 1982, and an album on the offshoot Factory Benelux (‘Sparks In A Dark Room’) the same year, after which Minny Pops returned to Plurex. Minny Pops drew to a halt in 1985 after a fourth album ‘4th Floor’, and Wally’s parallel career as a music industry executive blossomed. He revived Minny Pops in 2011 for some well-received shows, and there was a single with Tim Burgess’s O Genesis label in 2012 and there is, he says, new material under development. So nearly 40 years later, how does he look back on his time with Factory?

“Were we hoping for more? Yes. Did it happen? In the end, no. Factory had creativity, they had great ideas, but sometimes the execution was more difficult for them. Maybe they didn’t know how to do what they were doing. But it doesn’t matter, some great things came out of that.”