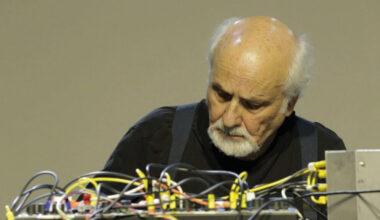

Mute Records founder, musician, producer, remixer and DJ, you name it, Daniel Miller has been there, done that, got the t-shirt, and most likely signed the band to his label…

Daniel Miller is not only a titan of the British electronic scene, he’s a hugely important global figure in independent music generally. Born to Austrian-Jewish refugee parents in North London in 1951, Miller initially studied film at college before the arrival of cheap synthesisers and drum machines liberated his musical ambitions. He launched the defiantly indie Mute label in 1978 with his seminal electro-punk seven-inch ‘Warm Leatherette’, released under the alias The Normal. Born from the DIY ethos of punk, the pioneering spirit of Mute was anti-elitist, experimental and adventurous. Little has changed 40 years later.

Mirroring his own eclectic tastes, Mute has always showcased leftfield electronic and industrial artists alongside platinum-selling pop stars. As the home of Depeche Mode, Yazoo, Erasure, Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds, Einstürzende Neubauten, Moby, Goldfrapp and more, the label enjoyed major success in the 1980s and 1990s.

But commercial pressures during the Britpop era drove Miller to sell Mute to EMI in 2002 for £23 million, although he remained in charge of operations. The merger unravelled in 2010, when he delicately negotiated a divorce from EMI and launched a rebooted version of Mute. His most recent star signings are electro-rock legends New Order, which feels like a perfect fit.

Alongside his label boss duties, he recently started DJing again, playing legendary venues such as Berghain in Berlin, Space in Ibiza and Sónar in Barcelona. This in turn le him to reactivate Mute’s techno offshoot Novamute, once a platform for for the likes of Richie Hawtin, Luke Slater and Miss Kittin.

As he warms up for his latest London DJ date, at the inaugural We Are Robots festival in the capital’s glittering East End, and the launch of a new book ‘Mute: A Visual Document’, Miller talks to Electronic Sound about his long and varied career.

Mute has always had a broad roster of acts: experimental, electronic, underground, but also pop. Is there some kind of shared spirit between all these acts?

“To me there is. I think it’s about quality, originality, sense of humour… exceptional is the word I like to use because it covers a lot of things. They don’t sound like somebody else. They might be out of time with whatever’s going on in music, but the music is great. It’s a hard thing to say, but I would just say exceptional artists and great people to work with.”

You’ve recently relaunched Mute’s specialist techno imprint Novamute with a new EP by Nicolas Bougaïeff. Why revive the label now after a dormant decade?

“In my recent phase of DJing I’ve been playing techno, the kind of music that would have been on Novamute when it was running before. And I just thought it would be great, now that I’m in a position where I know what I like and I think I know what works, to start putting out some records that would work for me and for others too. Hopefully we’ll be finding new things and working with some old friends as well.”

How does Novamute differ from Mute?

“It’s distinct in the sense that it’s a very specific techno label, it works very much within that genre. I think if it was within Mute it would be more difficult for people to understand what it is doing, if it was next to a Josh T Pearson release or next to a Goldfrapp release. It is genre specific so it’s quite good to have its own identity.”

What prompted you to start DJing again?

“I had no intention of doing it but a few years ago a friend of mine who DJs as Regis, Karl O’Connor, was living in Berlin and had a project called Sandwell District, which is a collective of DJs and producers. He was doing a party at Berghain and he asked me to DJ – I thought that was crazy, I know Berghain, I’ve been there and I love the music they play, but it’s a very specific thing. But he assured me it wasn’t too much pressure. So anyway I did it and realised it was something I’d like to do more of. So I now have an agent and do about 20 DJ slots a year, which is fine for me. Semi-pro, I think is the expression.”

But you were actually a club DJ in the 1970s before you started Mute, right?

“That was a very long time ago, quite a long time before Mute. I had kind of escaped London for while, did some travelling, ended up in a very beautiful place called Zermatt in Switzerland. I’m into skiing and applied for a job where they had a club. It was tourist place, just a club for people on holiday. I ended up doing two seasons there. I was playing the hits of the day, whether it was ABBA or Status Quo or ‘Kung Fu Fighting’, all the 1960s and 1970s hits. I enjoyed the experience of it even if I didn’t necessary like all the music I played. Playing music for people to enjoy is something I like to do, and that applies as much to a ski resort as it does to Berghain.”

Your parents were both actors and Austrian-Jewish refugees. Is there a connection between that kind of cultured, cosmopolitan background and your career in music?

“I think there must be. I never wanted to be an actor, but obviously I grew up around German Austrian culture, and they were open-minded about things I wanted to do in terms of jobs. I learned about the creative side of life early on, I studied film, went to film school, worked at doing that for while. Music was always my first love, but I couldn’t find a way through to it. But they were always very supportive, they created the space for me to do all that.”

Bizarrely, John Cleese once gave you some early career advice. How did that happen?

“There was a little group of us at school when we were about 16, in the sixth form, and for some reason we started writing comedy and performing it at school. We thought we were pretty good, ha! I don’t know if we were or weren’t, but John Cleese was quite well known then, just before Monty Python started there was a radio programme called ‘I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again’ and we were sort of influenced by that. So we wrote to him thinking he might give us some help or something. I’m not sure why we wrote to him, but he invited us down to see him and gave us some advice. And soon after that he invited us to see a Monty Python recording. Which was quite weird, because it was before they started broadcasting the show. They were recording the Nudge Nudge sketch and we didn’t have a clue what was going on, it just seemed completely crazy. But that was just as we were all leaving school and going our separate ways, so we didn’t really pursue it. It all just fizzled out after that.”

What’s the story behind your new book project, ‘Mute: A Visual Document’?

“Thames and Hudson, who are a high quality art book publisher, approached us to do a visual history of Mute and I thought that was very interesting idea. We’ve been approached over the years by various people to write a Mute biography and I’ve never really wanted to do it, but I think this is quite a good way of telling the story. I’m really happy with it. There’s a lot of artwork, a lot of photos, a bit of text, not too much. I think the difference between Mute and some of our contemporaries from the old days, Factory and 4AD in particular, they both had very distinct visual styles and really worked with just one artist for all their artwork. But when Mute started I always thought, ‘If I was a recording artist, I would want to be involved with the artwork myself, I wouldn’t want somebody else to impose artwork on me’. I think what Factory and 4AD did was great visually, I just prefer the artists I’m working with to dictate the direction of their artwork, if they want to.”

What drove you to sell Mute to EMI in 2002?

“The Britpop thing had a very powerful influence. It was the antithesis of what we were doing, and it was ubiquitous at the time so we struggled to get anything else through. The British media at the time, this was pre-internet, when the music papers still reigned supreme, and they just shut out everything that wasn’t Britpop. And the same for radio. Dance music was successful at that time, commercial dance music was doing well, Novamute were doing well, but we weren’t doing big superclub house music.”

So did you actually buy Mute back from EMI in 2010?

“Not really. I sold it in 2002 and then eight or nine years later we just left EMI. We didn’t buy it back, we just left. Anyone who thinks Brexit is going to take 18 months to sort out should try dealing with EMI! Ha! It took about two years to sort out, but we finally got there, amicably as well. Many of the artists we were working with at the time weren’t under contract so they came with us, and staff as well. Those who didn’t come over were Depeche Mode and Nick Cave, but that was their decision. We’d worked with both of them for a hell of a long time and they both quite reasonably wanted to try working with somebody else.”

So many legendary bands have been released or reissued under the Mute imprint over the years including Can, Kraftwerk, Cabaret Voltaire, Throbbing Gristle, and more recently New Order. Are there any big fish who got away?

“Yeah. Particularly Neu! A very frustrating situation. I think we spoke over a 10-year period, but unfortunately the two members, Klaus Dinger and Michael Rother, had had some massive falling out at some point after Neu! finished. They refused to talk to each other, refused to even sign the same piece of paper, so it was very difficult. They both liked the idea of working with Mute, but they couldn’t get over this incredible personal problem they had with each other.”

A lot of modern electronica seeks to self-consciously recreate the analogue synthpop sound that Mute pioneered in the 1980s. Do you think that is healthy for music?

“I look forward, not backward. I hear a lot of electronic music that sounds like it was made 30 years ago, and I don’t understand the point of that. What we were doing back then was trying to push music forward, away from the past. We might have been doing it in quite a crude way, but that’s what we were doing. So the idea of trying to recreate that is a nostalgic act, which I’m not that interested in. Some of the old synthesisers are great, I’m not going to deny that, but they should be put to good use and not just used to copy sounds from 30 years ago.”

Many would argue guitar music has run out of creative steam, do you ever worry electronic music will do the same?

“I don’t think the instruments are necessarily what brings the creativity to the music. I thought guitar music had actually had its day in 1967. But then I heard The Birthday Party and they were making sounds that were just unbelievable, using instruments in an incredibly creative way. So it’s not about the instrument so much. Creativity comes from the person behind it.”

You live part of the time in Berlin now, what’s the appeal?

“I was born and brought up in London, I know London very well, I think it’s a great city but it’s not very relaxed. It tends to be over-hyped and people are just in survival mode the whole time, so I don’t find it a very creative place really. Berlin has all the attributes of London, but much more space and time. And there are lots of nice places to go to. I don’t really go out clubbing in London ever, but I go out a lot in Berlin, it’s just much more inclusive. I’m getting on a bit and I often feel out of place in London, but I don’t feel like that in London. It’s less hierarchical in lots of different directions, and age is one of them. The other thing about Berlin is you can smoke in a lot of bars. I smoke cigars, not cigarettes, so that is better for me.”

Did you still own the vocoder machine that Kraftwerk used on ‘Autobahn’?

“Yeah! Ha! It doesn’t really work very well. I tried to get it fixed but it was a one-off, it was made especially for Kraftwerk and it was never really finished because they ran out of money. The guy wouldn’t finish it until they paid him, so it never really worked probably. It was actually first used on the ‘Ralf Und Florian’ album, before ‘Autobahn’. If you look the back of that album there’s a picture of their Kling Klang studio and you can actually see it in there. But it’s a beautiful thing, I’m very happy have that little piece of history.”

‘Mute: A Visual Document’ is published by Thames And Hudson