Not so much dancing to it, but certainly soundtracking it, Nicolas Godin’s second solo album, ‘Concrete And Glass’, pays tribute to the career he should have had if music hadn’t come calling…

“Claude Parent, Mies Van Der Rohe, Pierre Koenig, Le Corbusier, John Lautner, Richard Neutra, Melnikov,” intones Tanja Frinta on ‘What Makes Me Think About You’ from ‘Concrete And Glass’, the second solo album from Nicolas Godin.

Godin is best known as one half of Air with Jean-Benoît “JB” Dunckel. From 1998’s ‘Moon Safari’ to 2012’s ‘Le Voyage Dans La Lune’, Air produced some of the most lavish, elegant electronic music during a period where French provenance indicated a high watermark of quality. Dominated by lush, orchestral flourishes, exotic gestures and Godin’s vocodered singing, Air occupied a niche entirely of their own, yet they also nodded reverently in the direction of a quintessentially French pop and classical tradition.

‘Concrete And Glass’ is a full-circle moment for Godin’s musical career. It takes architecture as its thematic foundation, its 10 tracks originally conceived as the accompaniment for a global exhibition curated by the French artist Xavier Veilhan. The conceptual concern of the album returns Godin to his studies at the École Nationale Supérieure D’Architecture in Versailles around the time the first Air material was issued in 1995, back when it was predominantly a solo vehicle for Godin when he wasn’t making sketches and models of buildings.

“You could say that I have unfinished business with architecture,” he laughs.

With ‘Moon Safari’, Nicolas Godin and JB emerged into a Paris scene that was enjoying its overdue moment in the electronic limelight, and whose central figures exuded an effortless poise that seemed to be missing from the genre in cities like Berlin, Detroit or Manchester.

“It was very cool,” remembers Godin. “There was all this energy in the city and we were part of a movement of young musicians. We had some great nightclubs. Everybody knew everybody else. We used to make demos and listen to the tracks altogether. JB and I used to borrow some equipment from bands like Daft Punk and Phoenix. I felt very blessed to have had that once in my life. I imagine it’s what it was like being in London in the 1960s, or Laurel Canyon in the early 1970s, or Germany in the late 1970s. For me, 1996 and 1997 were amazing. It was fun to be there in the right place at the right time.”

What set French electronica apart wasn’t just its musicians – it was also its distinctive tonality. Compared with the rigidity of other contemporary music, what was being emitted from the Paris scene seemed to possess something richer and warmer.

“For some reason, when French people use electronic sounds, we do something romantic with it,” observes Godin. “When I go to a lot of other places, I see musicians using old synthesisers, and they’re always doing something kind of cheesy. French people have a good culture of electronic music, much more so than with rock music. It just has a different energy. I think it’s because our influences are a lot to do with Debussy and Ravel and Satie, with these kind of light chords that have no weight. I think it’s part of our culture, so when we record we are unavoidably influenced by that.”

Alongside a certain luxuriance to their arrangements, another distinctive element of Air’s music was Godin’s use of a vocoder, and that approach is audible again on ‘Concrete And Glass’. Godin considers himself a “very big vocoder geek”, admitting that using one allows him to work out his own style, and how to play alongside his voice in a way that he wouldn’t feel comfortable doing without it.

“I don’t know why, but I have this bond with the vocoder,” he says. “When I used the vocoder for the first time on ‘Le Soleil Est Près De Moi’ in 1996, I felt like it was my thing. I felt connected with the vocoder. It was like I could do everything very fast and very simply, all of a sudden.”

Even though he started out as a solo musician, Godin feels like he needs collaborators around him. ‘Concrete And Glass’ is a case in point – a Godin record, yet with many guest vocalists and a strong reliance on the guiding hand of a producer.

“I’m not a big fan of solo careers,” he confesses. “I’ve always preferred bands to when the members make solo records. I like the combination of personalities. Usually when bands split up it’s because there’s some tension, but that’s also why the music is great – because of all the opposition and the different views. I think when you’re by yourself you need to be careful. You need to work with someone who can critique what you do. When people make solo records, it can be very self-indulgent, and that was my fear. I didn’t want to do that.”

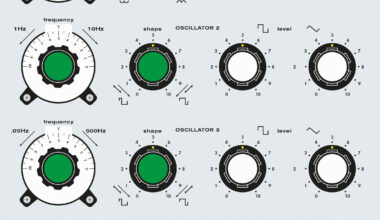

The involvement of producer Pierre Rousseau with what is ostensibly a solo Godin record might seem like a strange concept in the world of modern electronic music. Many musicians are programmed to work in splendid isolation, the role of a producer being of nebulous value when you can work for hours on a modular system offering limitless worlds of sound.

“Mainly, a producer helps you to avoid mistakes,” he argues. “I learned a lot from producers. Air worked with Nigel Godrich on 2004’s ‘Talkie Walkie’, and we did an amazing album with him. It’s one of my favourites. In the history of music, producers are so important. When you’re an artist, you do something good and you do something bad and you don’t see the difference, and it’s the producer who says to you, ‘This is better’. Good producers are like psychologists.”

Godin confesses to being overwhelmed by the sheer volume of tools available to the modern electronic musician – the endless synths, programs and plug-ins – preferring instead to compose with the piano.

“JB was the classical guy in Air,” he says. “I’m not classically trained – I didn’t learn music that way. I learned by watching TV. I watched it all day long as a child, so I learned music from soundtrack composers – that’s why my records have always sounded like John Barry or Ennio Morricone. When Air recorded ‘Pocket Symphony’ in 2006, I studied classical piano in a really intense way. I studied Bach for six years every day from nine o’clock in the morning until noon.”

With Air seemingly on indefinite hiatus, Godin’s first solo album, 2015’s ‘Contrepoint’, leaned heavily into his Bach studies.

“I wanted to have a testimony of what I’d done for six years, even if it was just for my family and my children, or even for me to remember what I’d been through,” he says. “So for me, that was more like a special side project, but now, with ‘Concrete And Glass’, it’s more like the kind of music I want to do.”

‘Concrete And Glass’ is indeed immediately different from ‘Contrepoint’. The Bach flourishes are nowhere to be seen, its structure resting instead on quietly fluctuating electronics and a more understated profile. It works on two levels – firstly as a rumination on the architects whose works inspired its creation, and secondly as a mature pop record.

“The concept is, for me, where to start,” explains Godin. “It helps me avoid the trap of the blank page. I feel like I need a reason to make a record, but once I’ve started I forget about the concept. With this project I began to look inside of me, much more so than when I do a collaboration with JB. It meant that I could do something very personal. When you’re in a band you can’t do that. When Roger Waters wrote a whole album about ‘The Wall’ the other guys in Pink Floyd went, ‘It’s not my story’, so it creates some tension. This was a chance for me to do something that I know. I really loved architecture, and I could have become an architect – it’s a job I thought I would have liked. This was a way to do a little bit of architecture… even if it is musical.”

The concept for what became ‘Concrete And Glass’ was presented to Godin by Xavier Veilhan. Veilhan was planning an exhibition in various houses around the world designed by notable architects. The enthusiasm with which Godin talks about the concept is infectious.

“We were going to see amazing houses. We were in Los Angeles, Barcelona, the South of France – loads of places – and it was a lot of fun. I’d never have thought of doing this by myself without Xavier suggesting it to me in the first place.”

The exhibition took in residences conceived by many architects that Godin was readily familiar with from his studies, such as the house in Beverly Hills that was designed by John Lautner and appeared as the porn magnate’s den in ‘The Big Lebowski’. His response to each of those locations was a site-specific, long, ambient work, and these formed the basis for the songs on ‘Concrete And Glass’.

“The chords, the harmonies and some of the melodies, they were all there in the pieces I did for Xavier,” he explains. “I just transformed them into songs so people can listen to the record without knowing anything about the original concept. I didn’t want anything pretentious – I wanted something pop, as I think that’s what I’m good at. I like to transform ambient things into pop things.”

For some purist experimentalists, the “pop” tag can be offensive. Godin isn’t remotely troubled by it.

“I like music that’s not boring,” he says. “My challenge is to make music that’s not very fast, but which doesn’t get boring, so that people think they’ve just listened to a pop record, but it isn’t obviously so. It’s more entertaining for people that way, and you don’t necessarily need culture to enjoy it.”

True to form, if it wasn’t for knowing the idea that framed the songs on ‘Concrete And Glass’, with the exception of a few isolated reference points, these are simply engaging electronic tracks that can be appreciated without needing to have spent three years working out the rudiments of building design.

Aside from the vocoder that makes a welcome appearance on a number of songs, another Godin trademark is the uncertain atmosphere that can be heard across the record.

“That’s one of my tricks,” he says. “For some reason there’s always a strange, melancholic vibe in all the music that I’ve done in the last 20 years. Always. It’s something I cannot run away from. Each time I start a song, there’s always a chord that makes the thing melancholic. I don’t understand it.”

Some of Nicolas Godin’s contemporaries from the Paris scene of the mid-90s packed away their Moogs years ago, whereas others are either unrecognisable from that time or still doing exactly the same thing. Godin, on the other hand, might have some trademark flourishes that make his music immediately recognisable as his own, but he’s still questing after something new. His choice of collaborators on ‘Concrete And Glass’ – Hot Chip’s Alexis Taylor, Cola Boyy, Kate NV and others – was driven entirely by that.

“I could have asked people that I know,” he sighs. “I know a lot of musicians and lots of singers and other people of my generation, but I wanted to have some fresh voices on this record. A lot of these people are young – honestly, I could be their father. The challenge was that I didn’t want to make music that felt like an old person who’s had plastic surgery.

“It was a big balance to find,” he concludes. “How could I make something that allowed me to keep my personality, but was also new at the same time? I wanted to change my habits, to think outside of my comfort zone. It’s difficult, but I like to think that’s what I did on this record.”

‘Concrete And Glass’ is out on Because