A life-changing conversation with Virginia’s hippest teenager, thwarted Hammond organ entrepreneurship, and 18 albums of classical synth suites… written on a ukulele. Enter the magical realm of Nikmis

Look up “Nikmis” using the internet search engine of your choice and the chances are, you’ll come across a mysterious 2010 entry on the Urban Dictionary website, which reads as follows: “Brainchild of William Simkin, a 17th century harpsichord player who, after a time travel experiment gone awry, has found himself stranded in the present day. William has taken a liking to modern-day synthesisers and has been quoted as calling them ‘manageable’. The project’s name stemmed from a childhood nightmare William had of a giant man/toast beast with the face of a cat. He dubbed the creature Nikmis, his last name backwards.”

“Somebody who listens to my music wrote that,” explains William Simkin over a crackly Skype connection from his home in the central Japanese prefecture of Gifu.

He’s Canadian by birth, but a peripatetic lifestyle that began during childhood seems to have ended – at least temporarily – in 2011, when he and his American wife, Nicole, settled in Japan to teach English. You didn’t write it yourself, then?

“It really is just my last name backwards.”

But you do use a particular piece of artwork on some of your releases, and it does look like a giant man/toast beast with the face of a cat.

“Yeah, there’s a picture of cat-bread. Like bread, with a cat face on it. I do use that, yeah.”

So where did that come from?

“I don’t know. I just thought it was funny, years ago.”

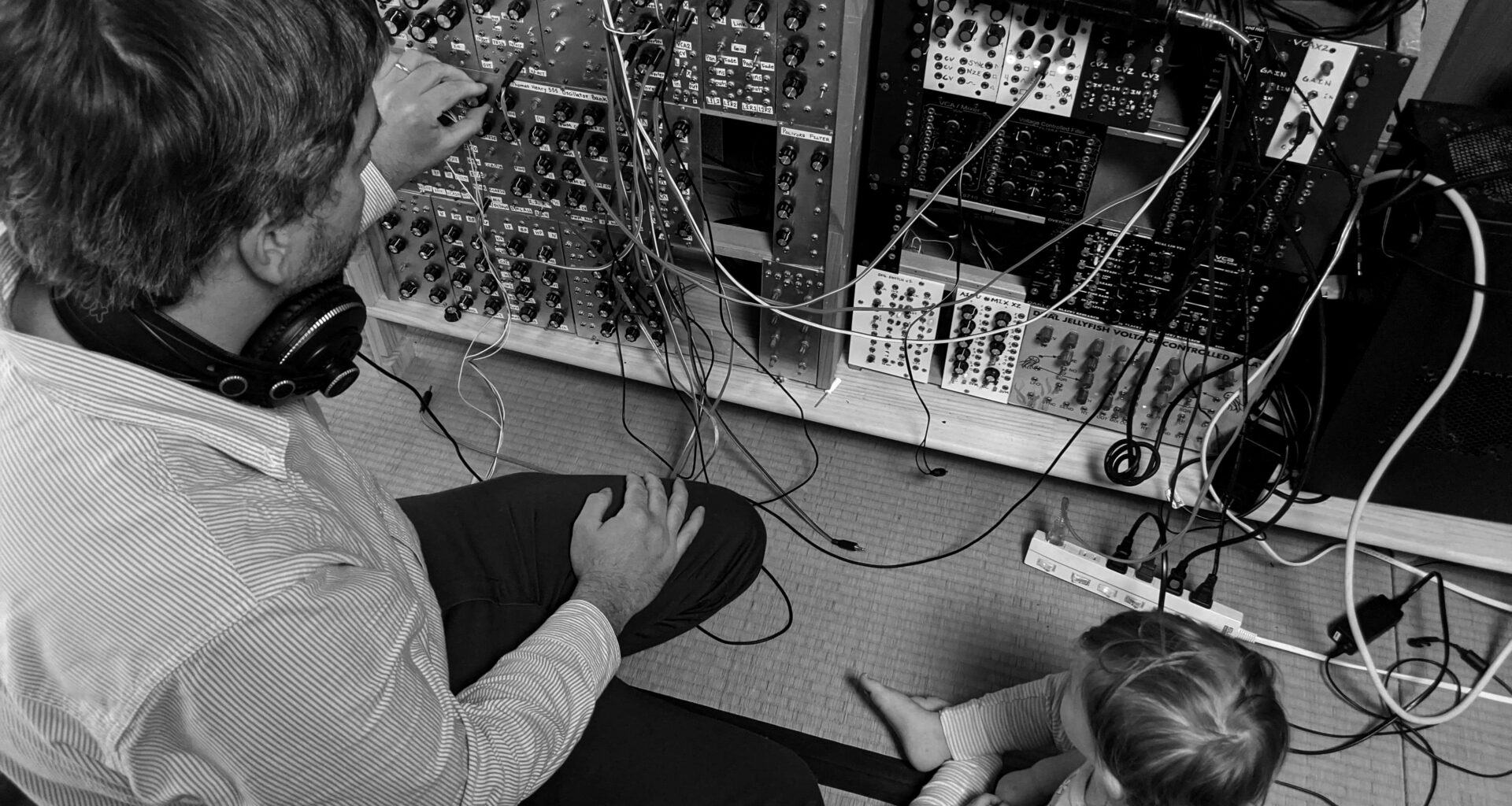

Nikmis is quietly eccentric and deeply enigmatic. The 33-year-old Simkin has just seen ‘Jawbone’, his 18th album in 14 years, released by Brighton’s Third Kind Tapes, and it is extraordinary. Truly. It comprises two suites of utterly transportive, classical-influenced music, apparently composed on the top string of a ukulele before being performed on the gigantic, home-built modular synthesiser that dominates the couple’s spare room.

The album dances and delights, being both wildly unpredictable and joyfully improbable, but it also has a sense of subtle purpose that gives the whole beautifully melodic escapade its own unorthodox, but unmistakable direction. Rather like a conversation with the man himself and indeed, the life that he describes.

Born in Calgary, and raised there until the age of five, Simkin then spent five years in Saudi Arabia before the family uprooted and moved, this time to Indiana. After a childhood immersed in his parents’ musical tastes (“Buddy Holly,” he replies, after a long pause, when asked about his earliest musical loves. “He’s my dad’s favourite.”) and a spell with the Northwest Indiana Youth Symphony Orchestra, playing double bass (“It was just big and cool, you know?”), his life was completely changed by a brief and casual conversation; an exchange that proved revelatory for Simkin, but seemingly less so for the other participant. Typically, it happened thousands of miles away from home, at a summer camp in Texas.

“Browning Stinson Keister,” he intones, sagely.

Sorry?

“I met him when I was 14 or 15. He was a little older, 16 or 17, and he was just cool. He had all these musical ideas. He listened to Wendy Carlos, and this extremely obscure group called Joy Electric.

“He also listened to classical music, and he said, ‘Wow, synthesisers are so great! You can turn the knobs on the front of these things and make any sound you want. It’d be really awesome if somebody tried to compose their own classical music with one’.”

“I didn’t know what a synthesiser was, but he put the idea into my head.”

It seems relevant to report that the voice Simkin has given to Keister in this anecdote – perhaps inadvertently, perhaps not – is that of The Fonz. So did that conversation provide the inspiration to immediately go out and snap up a synth?

“Well, completely unrelated to this, I briefly had a hobby where I found and restored old Hammond organs. America’s full of them. When I was 16, I was shopping for my first car in a local classified ads magazine in Indiana and I saw ‘Hammond organ, free with pick up’.

“I was curious, so me and my friend went to collect it. It was allegedly broken, but I took it home and, because I was a little technically-minded, I took it apart. Turns out they’ve got these spinning tone wheels inside of them, and it just needed some oil. I fixed it, and I sold it three weeks later for a few hundred dollars.

“So I did that a few times. After that I didn’t make much money, but I had fun playing Hammond organs, and that’s how it started with synthesisers.”

Moving back to Calgary for university, Simkin briefly played bass with a local band (“The guitarist jammed out on Metallica, while I stood there trying to play along. We didn’t have a name…”) before shelling out on his first synth, a Roland MC-202.

“I know that people who are into acid house think it’s like a poor man’s Roland TB-303, but I wasn’t making that kind of music, so I didn’t like the 303,” he admits.

The kind of music he was making, in fact, was a nascent form of the synth-based classical compositions which, five years on from that passing teenage conversation with the increasingly talismanic figure of Browning Stinson Keister, had begun to dominate his thoughts.

“I never saw the guy again, but at university I had so much time on my hands, I decided to start making that kind of music, and put it on the internet. And I ended up meeting another person on the internet who liked my music. His name is Robbie. He makes electronic synthpop as The Real Robbie.

“Robbie’s a roller-coaster enthusiast. He went on a trip to a roller-coaster park in Virginia, and was playing music to his friends, and said, ‘This is Nikmis’, and one of his friends said, ‘Wow, I really like that’. She sent me a message later, and we started talking, and it turned out Browning Stinson Keister lives on the same road as her! They go to the same coffee shop. We ended up getting married!”

Hang on… so a brief conversation with a random boy at a summer camp in Texas affected you so much that, five years later in Calgary, you started trying to emulate the music that he’d recommended to you. Your music was then taken at random to Virginia, where it not only led your future wife to fall in love with you, but she was living on the same road as the boy who started this whole bizarre journey in the first place?

“Weird, isn’t it?”

Have you contacted Browning Stinson Keister to tell him?

“He’s like, ‘Yeah, whatever…’ He’s still a cool guy.”

Given the nature of the Nikmis back catalogue, it’s tempting to conclude that Keister’s teenage recommendation of Wendy Carlos has been a profound influence, but Simkin seems a little jaded by the constant comparison.

“I actually never listened to Wendy Carlos until years and years later,” he explains. “I did see that movie… what’s the name of that movie?”

‘A Clockwork Orange’?

“I’d seen that movie, but I didn’t realise that was Wendy Carlos. Everyone is just referencing her first album, ‘Switched-On Bach’, right? Isao Tomita – that’s somebody who really used synthesisers to make classical music in a groundbreaking, amazing way. You listen to his album ‘Snowflakes Are Dancing’, or to Morton Subotnik’s ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’. Tomita was doing classical music for synthesisers, and it was beautiful and inventive.”

Simkin cites Stravinsky and Dvořák as his favourite classical composers.

“The romantic, early modern period. I’m not ‘classical’ classical.”

The first Nikmis album proper – ‘Eine Kleine Nekopanmusik’ – emerged on Bandcamp in 2007. Nekopan, it transpires, is a popular Japanese noughties discussion forum avatar, a loaf of bread with the face of a cat. Ah.

Subsequent albums have included ‘Nikmis And The Mystery Of The Blue-Blooded Wendigo’ (“Some ghost story from when I was a kid. I don’t know if my Grandpa told it to me,” muses Simkin, “I just remember, ‘You have to be quiet when you go to bed, or it’ll take you into the forest and eat your toes’.”) and ‘The Fantastical Nikmis Vs The Evil Dr Crobe’, whose title, it seems, derives from a “pretty bad” science fiction novel by Scientology founder L Ron Hubbard.

The albums, he claims, have no themes or overriding concepts, and the titles are apparently chosen with similarly random intent. ‘Hugo’, from ‘Jawbone’?

“A friend’s kid, but the name is completely arbitrary.”

What about ‘Vint’?

“The original file name was ‘Vintage’, but that was only because I was drinking wine at the time.”

‘Emma Jean’ forms a beautifully gentle section of the opening side to ‘Jawbone’, and is the name of his youngest daughter.

“That’s the name of our child, yes!” he chuckles. “I try to do my part as a father. I know some guys think that’s mom’s job, but I try to do as much as I can, and that usually involves putting the kids to bed. We have three kids, and we always end up singing to them, and Emma Jean has her own little melody that we sing. Me and my wife actually harmonise, we have our own parts that try to get her to sleep.”

Does it work?

“It used to…”

Simkin is charmingly self-effacing, and perhaps a little bemused by the attention. And he’s funny. Really funny. He plays every answer with a completely straight bat, and his deadpan responses sometimes bob like unexploded mines in a sea of conversation before the humour unexpectedly erupts from them.

And, over the course of his 18 albums, he has created his own world; a playful sonic roller-coaster that is both melodic and joyous. Despite his modest protestations (“Not a lot of people listen to my music… five or six steady people, and I’m internet friends with them all”) it feels like only a matter of time before Gifu constructs its own Nikmis theme park. The Real Robbie will be there like a shot.

With the conversation winding down, Simkin painstakingly describes his home-built modular synth. It’s a somewhat oversized contraption, largely due to his inability to cut down the aluminium sheeting from his local hardware store (“I don’t have the tools for that”).

As he talks, it becomes apparent that his wife Nicole has crept into the room some time before, and promptly dozed off.

“I’m awake!” she cries, not entirely convincingly. It’s late in Japan. We’re holding a conversation with a considerable time gap here. So, your husband was telling the full story of Browning Stinson Keister, and how this man seems to have inadvertently influenced the entire direction of both of your lives…

“It’s bizarre,” she confirms. “It’s like fate. The world is big and small at the same time. All the little teeny-tiny details that impact on peoples’ lives. Just one or two sentences…”

And with that, they begin an impromptu vocal recital of the original ‘Emma Jean’ song, harmonising beautifully into their Skype connection, halfway around a world that right now does, indeed, suddenly seem big and small at the same time.

Browning Stinson Keister isn’t mentioned on the Urban Dictionary website, but he is – a perfunctory internet search reveals – a real Virginia musician, and not the mysterious Keyser Söze figure that one might initially suspect. Nikmis, meanwhile, remains a tantalising enigma whose music, rather like its creator, gently fizzes with a rather strange and beautiful charisma.

‘Jawbone’ is out on Third Kind Tapes