The 71-year-old Parisian composer Philippe Besombes is a man whose work should have been enjoyed alongside that of his pal Jean-Michel Jarre. The story of this undiscovered electronic pioneer is quite a tale…

As a fervent disciple of pioneering electronic music for over 50 years, the recent appearance of a boxset containing four brilliant albums released in the 1970s by a little-known French composer called Philippe Besombes threw a large cat among my pigeons. ‘Anthology 1975-79’ invoked shame for not being aware of the artist Julian Cope has called “one of the greatest electronic musicians and sonic creative genii that we have ever had”, but happily that was outweighed by the frequently astonishing electronic soundscapes within.

Some knew Besombes’ name listed next to Tangerine Dream and TG on the sleeve of Nurse With Wound’s 1979 album, ‘Chance Meeting On A Dissecting Table Of A Sewing Machine And An Umbrella’, but that’s just a tiny footnote in his incredible tale. Even by 1979, he’d made albums that could have changed music if they’d been heard at the time.

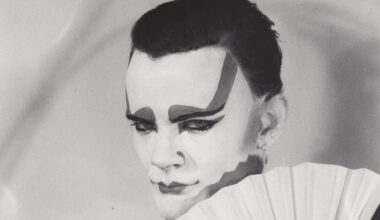

Happily, Philippe is still active at the age of 71 and relished the opportunity to talk to Electronic Sound, even engaging an English friend to help translate. During the interview a picture emerged of a veteran studio scientist on a mission to break new ground right from his late 60s beginnings. Born in Saint-Denis in 1946, Philippe’s life changed when he first heard Elvis Presley on a jukebox in the late 50s.

“I was 13 and it was exciting, something impalpable and underground,” says Philippe, “In 1959 I managed to get a copy of ‘Blue Suede Shoes’. The sleeve was striking, it showed Elvis playing the guitar like a madman. The music was violent, it was so incisive and the rhythm was fast. It was electric! We were young and hungry for those new sounds.

“In the early 60s, the Anglo-Saxon music began to wash over France despite the obstruction of major companies who preferred to release French covers of English or American songs. In 1963, I was staying in Sheffield in the UK and The Beatles’ ‘She Loves You’ was on the radio all the time. I felt like Christopher Columbus discovering America. I could hear the music that my French friends couldn’t because they didn’t know it existed, so I was 10 lengths ahead.

“Once I was back in France, I was thirsty for electric sounds; distortion, echo, and reverb. Even though I didn’t play the guitar well, it didn’t matter as long as my body was wrapped in those striking sounds. I remember my first experience in a recording studio when I pushed up the volume of my amp to create a marvellous distortion sound. The engineer ran up to me, explaining that the sound is nice when you put the volume at one or two… I was disappointed!”

Around 1966, Philippe became gripped by the free jazz being blasted by John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy and Sun Ra. He also enjoyed the trailblazing fusions being explored in France by outfits such as Magma and Gong.

“I couldn’t stand the naive melodies played on the radio,” he says. “I loved free jazz, but I couldn’t bear the way George Martin produced The Beatles now; they were influenced by the business industry.”

By now he was studying chemistry at the Sorbonne (and would earn his PhD in 1975), but he had started creating music in his ever-growing sound laboratory. He As PJF, with high school friend Jean Francois Dessoliers, he made his first recordings and composed music for Paris dance companies putting acoustic instruments through electronic devices and the generators he found at the CEA (Centre De L’Energie Atomique) flea market.

“I could change the speed and tone of the sound,” he explains. “I could slow it down with my hand, make it cry, turn back the tape, cut it and create loops, and the best of it was the rotating head tape recorder that was extremely rare at that time. I realized my own world of sounds. Nowadays I really hate all the machines sold with their sound banks so that everyone works with the same base. What’s the point?”

Some of Philippe’s rarest early work, created for ballet and theatre art festivals since the early 70s, was gathered together in 1976 on the remarkable ‘Esombeso (Ceci Est Cela)’ album, which is included in the new boxset. Just the hauntingly dismembered vocal flurries of the title track ‘Ceci Est Cela’ or brain-chilling theremin sweep of ‘Géant’ places Philippe Besombes among the era’s major innovators.

Between 1972 and 1974, Philippe organised bills for the annual Contemporary Music Festivals at La Rochelle, bringing to Paris names such as Pierre Boulez, Ennio Morricone, Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis.

“Xenakis was my senior,” he says of the electronic music pioneer. “We met at La Rochelle Festival in 1972. He appreciated my work both as a sound engineer and as a composer, and he very soon took me under his wing and often called on me. He was sensitive and tactful, but he could also be quite intimidating.”

Philippe recorded a rivetingly atmospheric double album for Pôle Records with Jean-Louis Rizet and explored new sounds with Jean Michel Jarre, who was at the time working on his landmark ‘Oxygène’ album.

“Jean Michel was one of my best friends’ cousins,” he explains. “We got on well as we shared the same desire to renew the electro-acoustic music. Compared to Pierre Henry, Pierre Schaeffer and Bernard Parmegiani, we were the new generation.”

The electro-acoustic experiments being conducted by Schaeffer and Henry proved major early influences.

“Pierre Henry was a popular composer despite his marginal approach,” offers Philippe. “When he worked with arranger/composer Michel Colombier it was the first time we had heard electronic music mixed with drum sounds. After that he was asked by a record company to ‘recompose’ an electro-rock album with British group Spooky Tooth [1969’s ‘Ceremony’]. The collaboration was amazing, but I felt there was no cohesion between the group and Pierre. It seemed he had just stuck sounds on the group’s recordings. Even if I loved the result, I was disappointed. I wanted to try and do the same.

“As a composer, I’ve always felt a deep attachment to the sounds, atmosphere, tone, depth, space and the message I want to convey rather than the notes and melodies. At the start of my career I wanted to communicate the thoughts of human beings confronted by the post-World War Two industrial world; their anxiety and fear of violence. The use of the tape recorder led me to unknown sounds: noise and screams. I didn’t want to settle for a compromise. I wanted to work with rock musicians too, and it was the music of ‘Libra’!”

Released in 1975, ‘Libra’ is the first disc of the boxset and is Philippe’s early electronic masterpiece; a 47-minute, 17-track collage exploring musical forms such as rock themes, tape manipulation, psychedelic excursions and treated voices.

“‘Libra’ was a film directed by Pattern Group,” he says. “The three directors of that group worked together and had already made a short film called ‘Eloah’, which made an impression. Their trick was to avoid the use of dialogue or voiceover because the image was supported by music, sound effects and colors. When they shot ‘Libra’, they did it at their own tempo, without worrying about the music. When they reached the post-production stage, they used Pink Floyd’s ‘Ummagumma’, but they did not have the rights as it would have cost a fortune.

“I found myself in charge of recreating an original new piece of music with the same feeling. I called guitarist Patrick Werbeck, drummer Jean François Leroi and bassist Alain Legros and we spent more than a month in my recording studio. Allan Jack, a Hammond organ player, played with us, there were also backing vocals, and I recorded a singer in a church during the night, where I got to play the church’s organ! Once finished we were far from the music played by Pink Floyd. The filmmakers liked it, I had saved their movie!”

Philippe constructed ‘Esombeso’ in 1976 when a label asked him for an album. Its early outings demonstrate a unique approach to creating electronic music, more in common with the veteran pioneers than the synth-enhanced artists of the time.

“I am sorry to say, but using synthesisers was choosing the easy way,” he scoffs. “Even if the sound was beautiful it was formatted into very commonplace elevator music. I tried to limit the use of synthesisers, using my tricks with tape recorders, using them as creative tools instead.”

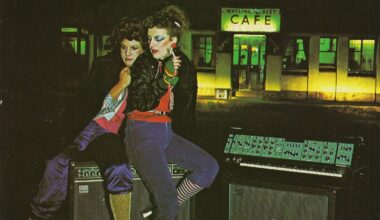

In late 1976 Philippe armed himself with new synths and formed Hydravion to explore post-punk electronic rock, predicting mutant disco with what he describes as their “electro-live” sound on 1977’s ‘Hydravion’ and 1979’s ‘Stratos Airlines’.

“I wanted to free myself from the classical atmosphere of French contemporary music and set up a new group with Cooky Rhinoceros, a virtuoso on his Gibson double neck guitar, and Chris St Roch who played bass and had been my partner since ‘Libra’. We mixed rock, electro sequences and samples played live with tape recorders. Unfortunately, our musical experience came to an end.”

Overwhelmed by disco producers then rock bands wanting to book the studio, Philippe moved to the Versailles Station studio he still runs today.

“I had to live, eat, pay the bills, buy equipment so I started renting my studio for sessions and it was soon overbooked. It was the most unique rock ‘n’ roll centre in the area. People from future famous bands came for sessions or just visited, including Air and Daft Punk.”

Survival also led to making ambient concept albums.

“I had to dedicate myself to my business and recording studio,” he says. “RCA decided to create a collection of soundtrack albums and ordered two; ‘Animal’s War’ and ‘City And Industry’. In 1986, I bought an SSL board and was ranked in the top 10 French recording studios. A lot of French as well as international artists were booked into my studio, including Manowar, Motörhead, Whitesnake, even Herbie Hancock because I had an 88-note Fender Keyboard.

“Sony began to order ready-made albums. They gave me a theme; relaxing music, music for babies, electro music, while they focused on marketing. Thus ‘Arno Du Chesnay’ (a techno-electro set), ‘Rondinara’ (music for babies) and the ‘Cosmos’ album (for Sony’s ‘Musique & Nature’ series) were born. They sold up to half a million copies. It was cool to get paid for writing music, but it was a trap. Working for manufacturers or advertising companies was far from what I had dreamt in the 70s.”

Philippe says he “hung up my boots” when his partner had their daughter.

“She is now 13, and a wonderful classical viola player. She is a student in the Music Conservatory in Versailles and I spend most of my time coaching her.”

Even if he was eventually forced into the mainstream to make a living, Philippe Besombes has already left a mighty footprint containing some of the most remarkable electronic innovations of the 70s. Do check him out.

‘Anthology 1975-1979’ is out on Cleopatra