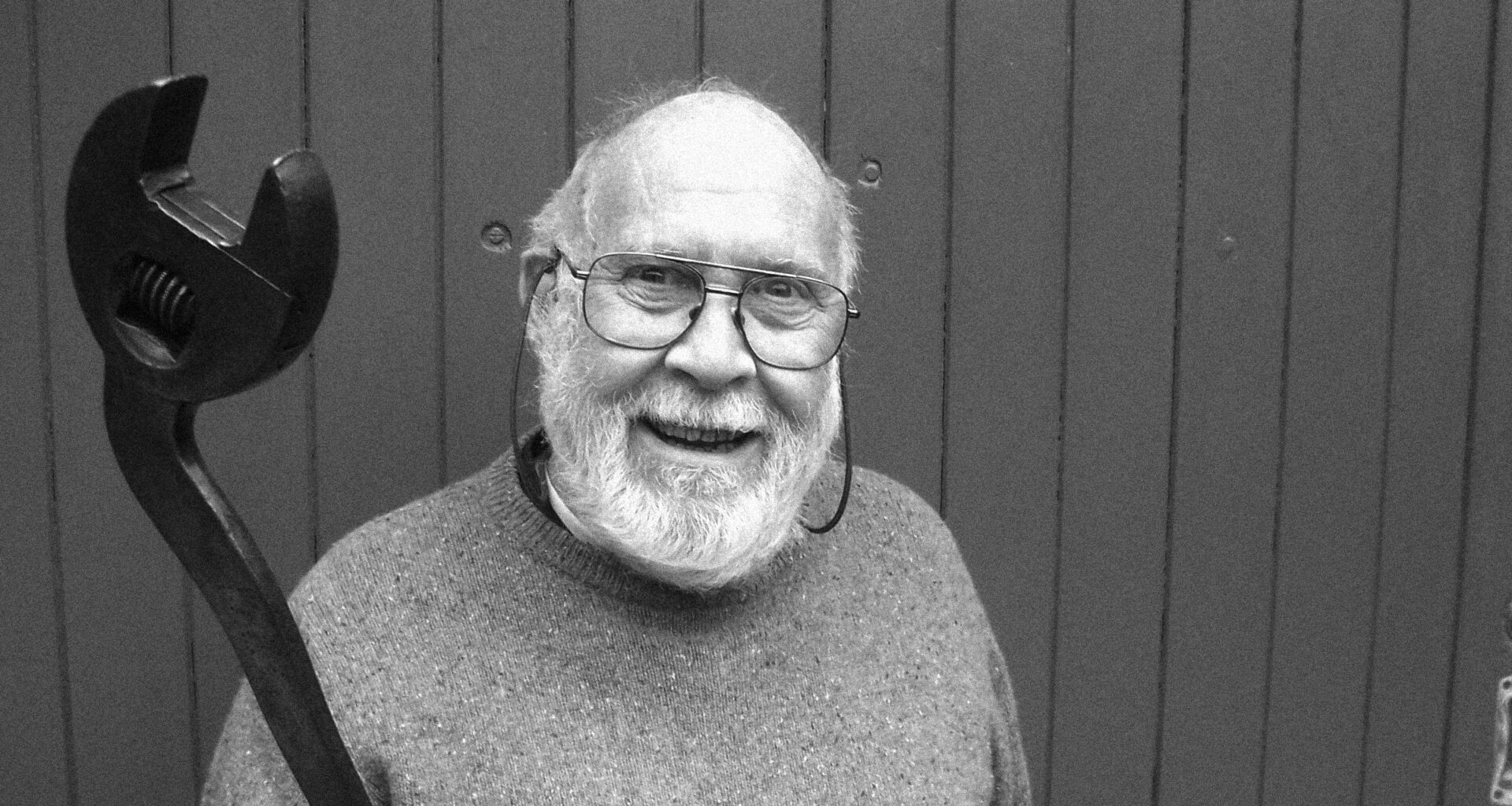

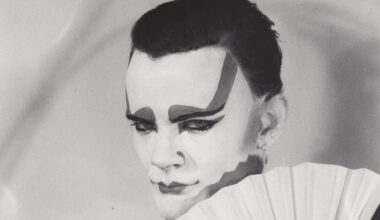

Brass knuckledusters, adjustable spanners, Pink Floyd collaborations and a surprising surplus of Bramley apples. In a secluded nook of East Sussex lies the unusual world of Ron Geesin

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here