It was one of the first electronic records to hit the charts all over the world. It launched the space disco genre and laid down a marker for synthpop. The story of Space and ‘Magic Fly’ is quite a tale too. Take your protein pills and put your helmet on

Just over 40 years ago, dancefloors across the world were smitten with a seven-inch single that sounded like it had arrived from somewhere beyond our galaxy, a strange alien melody threading its way across a bed of perfectly regimented, discothèque-friendly rhythms.

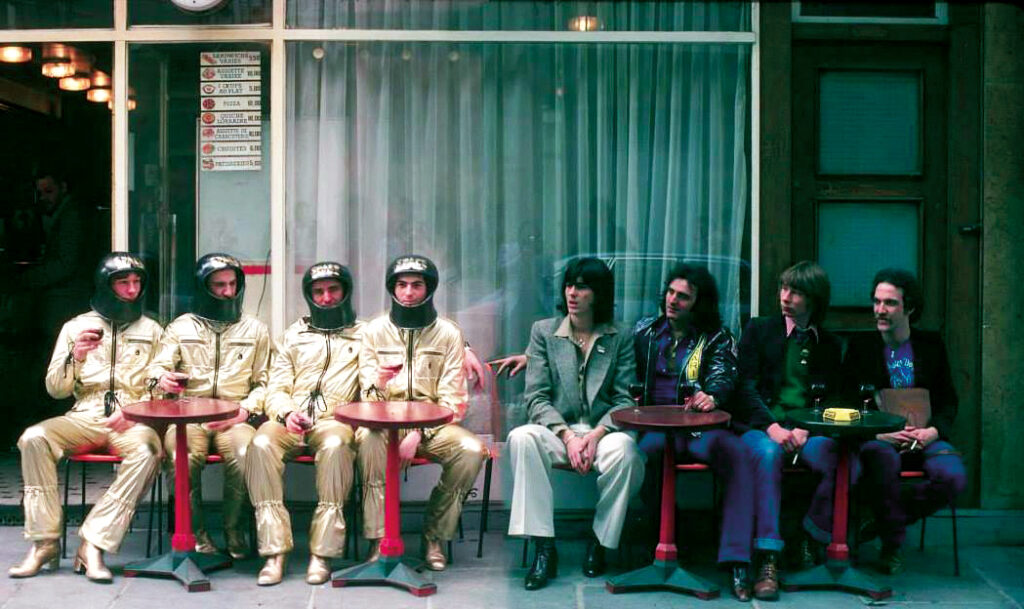

The track was ‘Magic Fly’ by a mysterious band called Space, whose members’ identities were shielded by cosmonaut helmets. But beneath those helmets, and behind the studio controls, were a group of talented session musicians, a highly-skilled producer and promoter, and an award-winning, classically-schooled French singer-songwriter with a proclivity for composing memorable synth hooks.

‘Magic Fly’ orbited the upper reaches of the world’s singles charts in 1977, only prevented from securing a Number One here in the UK because of the inconvenient passing of Elvis Presley. The song was innovative, ahead of its time, and an undeniably significant moment in the genesis of synthpop, then just a few Earth years away. It presaged three albums of similarly astral synth music, but Space’s outward success disguised disagreements over control between its songwriter and its producer, tensions over how to take the band’s popularity to the next level, a loss of identity and many years of lawsuits.

Space founder Didier Marouani was born in Monaco in 1953 into a French show business dynasty.

“I always knew that I would become successful too,” he says. “Since I was five or six, I was used to seeing famous people – big, well-known singers – coming to have dinner at our home.”

At the age of five, Didier Marouani decided to take up the piano, religiously practising before school at 5am every day. His prodigious talent with the instrument soon far outstripped the abilities of the first teacher his father had taken him to.

“My second teacher really made me love music,” he recalls. “I mean, I was loving music already but at that age you don’t really appreciate it. That teacher, she taught me that the main thing with music is it’s all about transmitting emotion.”

Transferring to the Conservatoire de Paris as a teenager, he continued with the solid work ethic his father had instilled in him, rehearsing and studying several hours each day, but slowly realising that he wanted to be a composer not a concert pianist. In the twilight years of his teens, Marouani decided to submit one of his compositions, ‘Tous Les Soleils Du Monde’, to a song contest being held at the Tokyo Music Festival. He was surprised to find himself being selected to represent France.

“I sent the song as a composer, not a singer,” he laughs. “My father received a telex saying I’d be representing France at the festival. I’d just made a demo of the song to present it, not to sing it myself!”

Marouani was eventually persuaded to go to Tokyo as the singer he didn’t think he was and, to his eternal amazement, he won the top prize, despite facing competition from established artists like Olivia Newton John and Paul Williams. He was suddenly catapulted into the role of the handsome, well-groomed French chanteur, recording solo records and touring with French music royalty like Johnny Hallyday, Charles Aznavour, Claude François and Joe Dassin. It was a charmed life, just not the one that Marouani had planned.

During his time as a singer-songwriter, Didier Marouani was introduced to promoter and producer Jean-Philippe Iliesco De Grimaldi, or JP as most people called him. Iliesco had made his name during the 1968 French riots, booking British acts to play for predominantly student audiences in Paris.

Using his business nous, JP Iliesco subsquently set up a company making advertising jingles. It was then that he learned his craft in the studio – what worked, what got people’s attention, what sold products – all of which he would eventually bring to the recording of Space’s ‘Magic Fly’ to make it a commercial success.

“I met Didier Marouani when I was going to a concert with the manager of Trident Studios in London, which I was already using to do some of my best productions,” said Iliesco in a video interview shot before his death in 2015. “This guy had come to Paris to see an artist who was about to record their next album at Trident. As we walked out in the crowd, he said, ‘Do you know this guy? It’s Didier Marouani. You should record his next album’. And I said, ‘Well, introduce me to him, it sounds interesting’.”

Marouani and Iliesco were both still operating in the traditional world of French popular music at that point. But it wasn’t long after they’d first met that Iliesco was commissioned to produce the theme tune for a French television show about astrology, an event that manoeuvred ‘Magic Fly’ to the launchpad. Iliesco asked Marouani to compose the music and his new friend jumped at the chance.

The commission was perfect timing because Marouani, impressed by the likes of Tangerine Dream, had just decided to buy himself an analogue synth, choosing a simple single-oscillator ARP Axxe.

“It was an honour for me to work on this kind of musical theme,” recalls Marouani. “When I bought the ARP, I came back to my home and quickly set up the synthesiser. When I got the right sound, it took me five minutes to compose ‘Magic Fly’. Five minutes!”

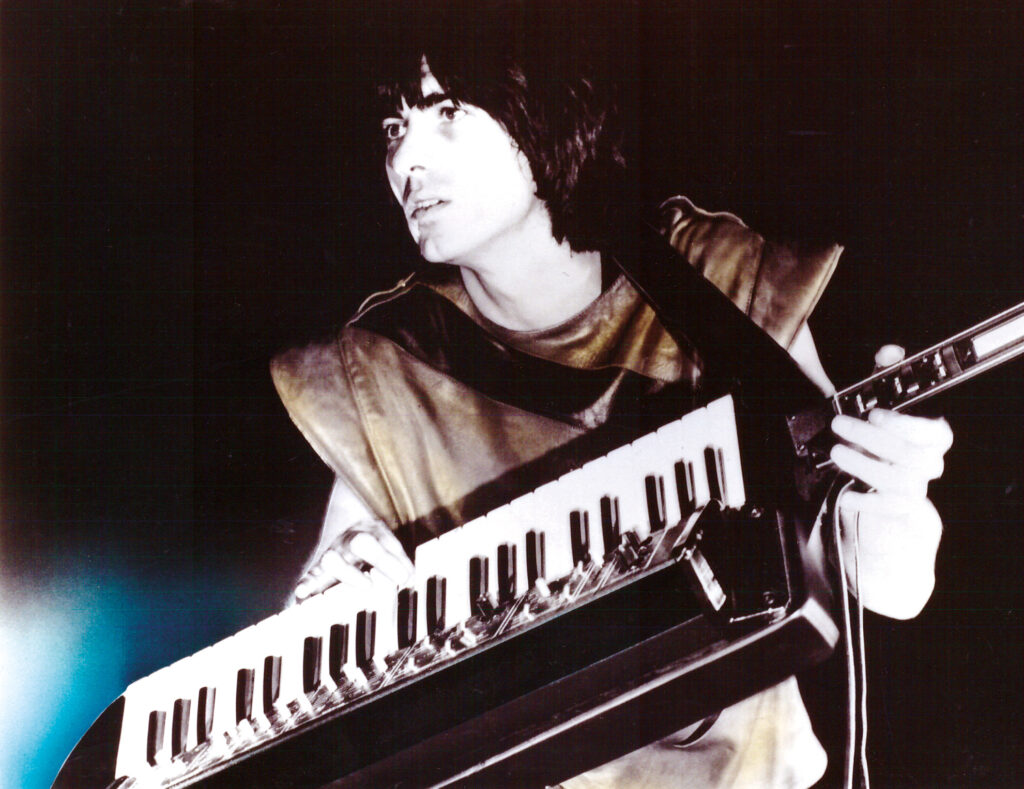

The original version of ‘Magic Fly’ was essentially a slow, semi-classical, austere piece of music, one that was probably a perfect fit for a 1970s astrology TV programme. Marouani and Iliesco hired Roland Romanelli, an accordionist who was also a skilled synth player, to help them record the track, but this ‘Magic Fly’ never got beyond the demo stage because the TV show was cancelled before filming had even started. Nevertheless, Marouani realised they had something with the track.

“The demo didn’t have beats,” says Marouani. “It was completely spacey – just the ARP melody and other synthesisers. But I knew that it was good. I was making all my friends listen to the demo and everyone who heard it told me it was a huge hit.”

Buoyed by the feedback, Iliesco took the tape to Polydor Records, who had released Marouani’s solo material, only to be met with a shrug of the shoulders and a shake of the head.

“They said, ‘This? We will never release that. It’s awful. No way’,” remembers Marouani. “I was really disappointed because I wanted so much to record this song and to start making electronic music.”

With no record company interest, Iliesco suggested altering the structure of the track to make it fit in with the disco songs that were creating a buzz at the time.

“I had been in my office listening to the tape over and over again thinking, ‘What can I do with this?’,” said Iliesco. “Kraftwerk were Number One in France at that time and I said, ‘That’s it, I’m going to make an electronic dance record’. I called Didier and I said, ‘We’re going to double the tempo and put a bass drum all the way through it’. And he said, ‘Are you crazy?’.”

But once Marouani had got his head round the idea, he suggested taking his name out of the equation to avoid detection by Polydor.

“I said to JP, ‘Let’s forget all about Didier Marouani. Let’s make a band’. Everyone who had heard the track had said it seemed to come from space, so we decided to call the band Space. It was that simple.”

To further shroud his involvement, Marouani adopted the name Ecama as the songwriter of Space’s material, using the first two letters of his wife’s name and the first two letters of his surname. It was something he would later deeply regret. JP Iliesco meanwhile brokered a deal with Léon Cabat, the founder of the Disques Vogue label, to release the new version of ‘Magic Fly’. Cabat booked the band into Disques Vogue’s in-house studio in Villetaneuse in the northern suburbs of Paris.

The recording sessions were not without difficulties. Developing the metronomic, repetitive beat that runs the full length of the ‘Magic Fly’ seven-inch required a particularly painstaking approach. The responsibility fell to American session drummer Joe Hammer, who was then living in Paris and had worked on other sessions with Iliesco and Romanelli. He would later go on to work with Jean-Michel Jarre and as a Fairlight specialist.

“This was starting to be no big deal back then, as a lot of us studio musicians were laying down very sterile and mechanical-sounding drum tracks,” says Hammer. “I played directly to the song’s bass sequence, which was triggered by a Korg Mini Pops 120 drum machine. I put down a clinical bass drum first, then the snare sound, and then the little hi-hat part, which JP flanged and phased. I had to make sure that my playing was completely robotic. The entire process took four full days.”

“When he finished, Joe said, ‘Do you mind playing me the music that goes on top because I have a headache from the click track’,” recalled Iliesco in his video interview. “I played him the ballad demo and he said, ‘You’re a criminal!’. We mixed it all in two hours and finished it at two in the morning. When I played the rough mix to Léon Cabat and a few other people, they said it was really good. I spent four days trying to make a better mix, and I never got a better one than the rough version. So that’s what we released.”

There was still one problem, however. Despite distancing his name from Space, Didier Marouani’s face was well known in France. Particularly by Polydor, the record label he was contracted to.

“So I suggested we made a video clip to promote the record,” he says. “We made it in London and we dressed as cosmonauts, with helmets on our heads, so nobody would recognise me.”

The ’Magic Fly’ video, still charming to this day in a slightly kitsch way, presented Space as a four-piece unit, even though only three people had played on the track. To complete the band for the video, they hired John “Rhino” Edwards, later of Status Quo, to mime the synth bassline. The ruse worked. Polydor were none the wiser and ‘Magic Fly’ became a massive global hit. The track also earned Iliesco a best producer award in Germany, which he shared with ABBA producer Stig Anderson and Giorgio Moroder.

Space subsequently recorded an album, also called ‘Magic Fly’. Based around a concept detailing a journey into space and with Jannick Top from Magma playing bass, it was a clever, ever-so-slightly out-there entry point into electronic music for lots of people. Joe Hammer didn’t have to repeat that punishing studio exercise too often and the rest of the album charted a jazzier, looser and more experimental course through the space disco vibe. The record was fully instrumental except for the closing track, ‘Carry On, Turn Me On’, JP Iliesco’s attempt to get airtime in the US. It worked and he was soon hanging out in Studio 54 in New York with its attendant crowd of celebrities, hangers-on and criminals.

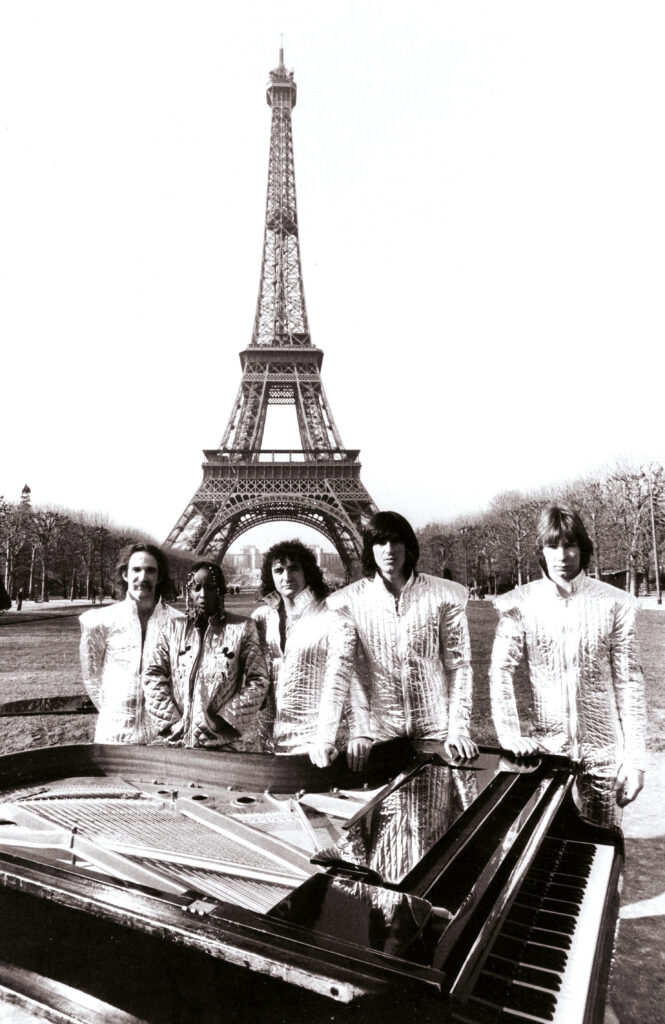

Another Space album, ‘Deliverance’, followed later in 1977, while Didier Marouani also delivered his final release for Polydor and completed a 40-gig summer tour with Joe Dassin. It was a turbulent and incredibly busy year for Marouani, but one that saw him enjoy success in two completely different fields. When the third Space album, ‘Just Blue’, was released by Disques Vogue in 1978, Marouani was out of contract and no longer needed to hide behind his cosmonaut’s helmet, doing a theatrical reveal of his real identity on a French TV prime time news programme.

By this point, Marouani was also desperate to take Space out on tour, something that hadn’t been easy to do before.

“It was just after we’d recorded ’Just Blue’,” he says. “I told JP that we needed to tour that album, we needed to play live shows. We had an authorisation from the Préfet de Police in Paris to put on a concert beneath the Eiffel Tower, we’d even had promotion photos taken near the Eiffel Tower in our cosmonaut suits, but there were problems because of the contract JP had negotiated. I told him I’d quit the band if he cancelled the concert. He told me, ‘OK Didier, do whatever you want, because I’ve deposited the name Space at the trademarks office under my name. So you want to quit? Quit’.”

And quit he did. He might have been no longer able to use the Space moniker, but in just two weeks Marouani had regrouped with Roland Romanelli and Joe Hammer as Paris-France-Transit, finally allowing him to take his music out on the road. Losing control of his intellectual property was a bitter pill to swallow, though. Six years of bitter feuds and complex lawsuits now occupied the vacuum left by Space, until Marouani was finally able to secure the copyright to the band’s name and buy back his publishing rights from Jean-Philippe Iliesco in 1984.

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

But there’s one final weird twist to the Space story. ‘Magic Fly’ charted pretty much everywhere in the world, but it would be the Soviet Union that really embraced the band’s music. Marouani played his first live shows with Paris-France-Transit in the USSR, performing three Moscow gigs to a total of 320,000 fans, and he continues to sell out massive venues on Russian tours to this day.

One reason for this is most likely Marouani’s close relationship with Roscosmos, the Russian Ministry of Space. He was granted unprecedented access to the upper echelons of the Ministry, allowing him to pull off some outlandish stunts. For the ‘Space Opera’ album in 1987, for instance, he obtained Mikhail Gorbachev’s personal approval to use the Red Army Choir and negotiated for its first public play to be in space, aboard the Mir space station.

“Throughout my early career, I saw so many singers go completely crazy,” reflects Didier Marouani from the comfortable position of 40 years of success. “I always knew that I would never change. Never ever. When you are famous, the people around you will keep telling you that you’re so good, you’re so talented, but it’s just the bullshit that floats around people that have found fame. For me, I’ve always tried keep my mind in space, but my feet firmly on the earth.”

With thanks to John Bryan for the use of his archive video interview with Jean-Philippe Iliesco