Their transition from arty hippies to electronic music’s most famous robots would appear to be more of a masterstoke than first meets the eye

It was 40 years ago this month that Kraftwerk released ‘Trans-Europe Express’. It was a momentous release for many reasons. It became part of the foundation myth of hip hop, of course, an electro blueprint, but closer to home it was the track ‘Showroom Dummies’ (or, to put it in its original mouthful of a German compound noun, ‘Schaufensterpuppen’) which signalled the beginning of Kraftwerk’s own rapid, career-defining self-mechanisation. The song’s narrative bears an uncanny resemblance to a key scene from a 1971 ‘Doctor Who’ episode that featured the Autons, an alien species with the unsual ability to animate plastic. Their evil plot saw 1970s suburban London rendered a hellhole of man-eating inflatable sofas and gun-toting shop mannequins breaking out of their shop window glass cages in order to rampage mercilessly (although quite slowly) through the streets.

It’s not a matter of record whether Ralf and Florian ever saw ‘Doctor Who’, but if they had, the scene might have resonated with them. The showroom dummy is something of a Düsseldorf speciality. The city is a centre of Germany’s fashion industry, hosting large scale expos for the serious business of high street fashion. As a result, the place teems with photographic studios, model agencies, in-store display fabricators and other support industries, including mannequin designers. In Düsseldorf, the mannequin has always been an art form, beautiful and tireless workers who could stand in for frail human models. And as Kraftwerk transformed themselves from avant-garde art hippies of the early 1970s into well-dressed and groomed young men, the impassive face of the ultra-sophisticated showroom dummy gave them something to hang their image onto, literally.

With its sinister, almost whispered delivery of the line “We are showroom dummies!” (or, if you prefer, “Wir sind schaufensterpuppen!”), Ralf describes how he and his plastic pals, like the Autons, start to move, and break the glass, and take a walk through the city. They end up dancing in a nightclub, which is where Kraftwerk and ‘Doctor Who’ sadly part company.

But it is in this amusing little vignette – for which they also shot a promotional film that further blurred the lines between the band and their plastic doppelgängers – that the seeds of the roboticisation of Kraftwerk are sown.

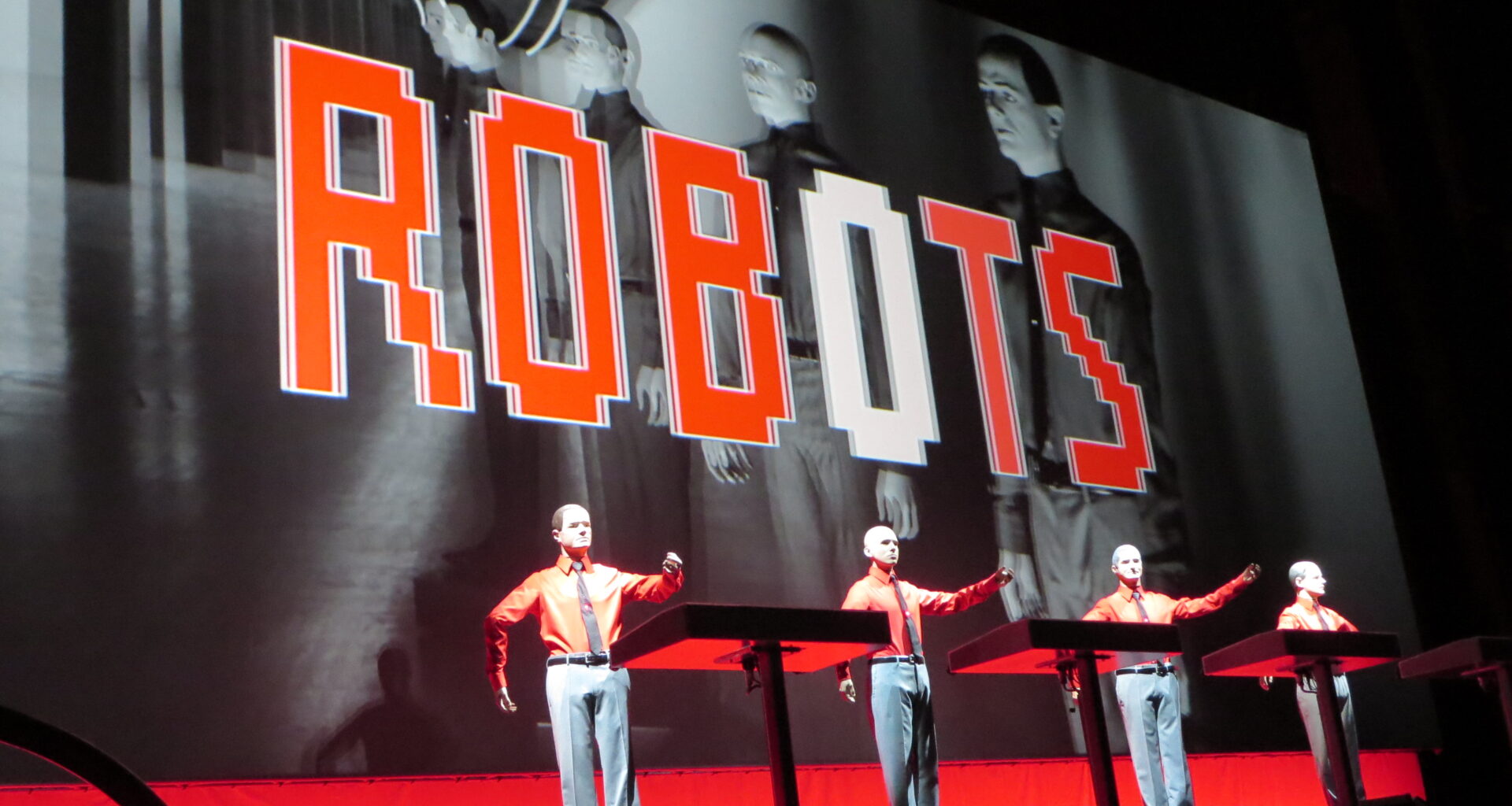

By 1978, robots took centre stage in the Kraftwerk oeuvre. When they unveiled ‘The Man-Machine’ (initially called ‘Dynamo’, dropped to avoid any football, erm, associations) at a press launch in Paris, they appeared alongside their own mannequins, the humans wore black shirts and red tie, the mannequins had red shirts and black ties. To the vodka and caviar befuddled music press who were invited, ‘The Man-Machine’ looked and felt like a concept album about robots, thanks in part to the artwork, created by artist Karl Klefisch, in the style of Russian constructivist El Lissitzky. The cover art and the idea were so riveting and brilliantly executed that the suspicion that Kraftwerk perhaps actually were automata of some sort was confirmed. If it sounds like a robot, and it looks like a robot, then godammit, it must be a robot.

Kraftwerk had turned themselves into machines, impassive, precise, metallic and inhuman. The robots both superseded and somehow confirmed the idea that Kraftwerk were toying with totalitarian imagery. For Ralf Hütter, the robots enabled an important distinction between the band and what people want bands to be. “The whole ego aspect of music is boring,” he told Record Mirror in February 1982.

“It doesn’t interest us. In Germany in the 1930s we had a system of superstardom with Mr Adolf from Austria and so there is no interest for me in this ‘cult of personality’… our machine-like state is maybe a step to being born in a new society. By bringing machines back to life again, we make them our friends. We treat them cooperatively as an equal part of the working process.”

“Automatic, ‘auteurs’, autistic…” wrote Jon Savage in his review of the album in Sounds, and perhaps tucked into this slightly insensitive alliteration is a nugget of truth. The robots could stand in for the band, and in particular for its two uncomfortable, publicity shy architects, Ralf und Florian. The concept behind ‘The Man-Machine’ segued neatly into the ‘Computer World’ album three years later, computers occupying a similar psychic space to robots in that they’re machines without emotions, just technology designed for data processing, all very calming for the personality type easily overwhelmed and ill-at-ease with the unpredictable nature of humans. And as the Kraftwerk project trundled on, exploring the intersection of man and machine via the medium of the bicycle, it slowly haemorrhaged members until just Ralf was left to manage the Kraftwerk legacy alone, finessing it by increment, the band now an enormous benign technological carapace, touring the world.

The architect and designer Le Corbusier – a friend of Florian Schneider’s celebrated architect father – famously said that a house is machine for living in. And perhaps that is what Kraftwerk has become: a machine for Ralf Hütter to live in.