Plotting a course through the world of electronic music in 50 key releases seemed like a great idea when we came up with it, but it quickly turned into an all-consuming monster.

Even if we had been able to include every record we had on our long list (and it was seriously long), there would still be so many missing. And even if we’d have included every record that every writer on Electronic Sound has ever heard, we know that our readers would be pointing out glaring omissions (“I can’t believe you failed to mention K-2’s essential 1980 release ‘Why’, I suppose you just don’t care about the electronic music of communist Yugoslavia” etc).

The hardest part was the countless records we left out which could have told the story of electronic music just as effectively. So these 50 records are the end result of a great deal of list-making, head-scratching, eyebrow raising, bartering, confrontation and more than a few late nights. It’s just one way of understanding electronic music’s history, one which doesn’t mention Ussachevsky, Raymond Scott or Berangere Maximin or… well, you get the idea.

Drawing Our Line In The Sand

It all started somewhere… but where?

In the time before synthesiser companies and before the record industry became the pop music behemoth of the 1960s and beyond, when Robert Moog was still in nappies, electronic music was the domain of isolated attempts by individuals to turn the world on to new sounds.

As time went by, the story of electronic music became defined by two parallel narratives; one of private enterprise, from boffins in their garden sheds to huge corporations like RCA, and the other of publicly supported studios, usually a nation’s national broadcasting company; the BBC in the UK, RTF in France, WDR in Germany, NHK in Japan and so on. There was much movement between the two and quite often individual inventors were keen to get any financial backing at all, and would have taken it from private investors or government departments.

The privateers are probably best understood as a patchwork of individuals, mostly unconnected and working independently, labouring away in sheds and backrooms and laboratories. Electronic music’s development relied on visionaries who had a peculiar blend of technical know-how and a strong creative impulse. Some, like the Russian inventor Leon Theremin, were sponsored by governments keen to invest in dazzling new technologies. Theremin’s support came from Stalin, possibly not the safest source of patronage in the 1930s, but his instrument, the theremin, was taken up by RCA in America and commercialised. It was RCA who later developed the first machine to be called a synthesiser, in the 1950s, but didn’t exploit it commercially.

Honorable mentions should go to people such as Maurice Martenot, who invented the ondes Martenot in 1928, which was similar to a theremin, but added more timbre controls and effects to the concept, and Raymond Scott who cranked out music for TV and film (and cartoons, Scott scored dozens of ‘Looney Tunes’ episodes in his time), made a stack of cash and spent most of it on filling rooms with intimidating electronic equipment to further their journeys into sound. These lone wolves of electronic sound were often obsessive and eccentric characters, like Louis and Bebe Barron, the married couple who soundtracked the Hollywood sci-fi hit ‘Forbidden Planet’ with their roomful of wonky oscillators (and, as it happens, a theremin) in 1956.

But while these early developments are critical, we’ve chosen to stick our flag into 1966 as a not-entirely-arbitrary start point for the modern age of electronic music…

The Originators

August 1966

The Beatles

‘Tomorrow Never Knows’

(Parlophone)

Although the song was a Lennon composition, it was McCartney whose musical antennae had picked up the output of the Cologne Electronic Music studio, where Stockhausen was using electronic tones and tapes to create highbrow experimental new music. While Lennon was dropping acid in his Weybridge mansion, exploring his own psyche and ruing the day he got married and chose suburban life, McCartney was at the epicentre of swinging London, mixing with the likes of Barry Miles, co-owner of the Indica Gallery and lightning rod for London’s emerging counterculture scene.

Miles introduced Paul to the music of Stockhausen (and, incidentally, hash brownies). To close that particular electronic circuit, Miles later was put in charge of the Apple Corp subsidiary Zapple, which released George Harrison’s ‘Electronic Sound’. McCartney, excited by his discovery of electronic and tape music, encouraged his fellow Beatles to create the tape loops that would play such a powerful part in ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’. The loops, together with the drones inspired by Indian raga and reminiscent of LaMonte Young’s work, and other studio tricks like the heavily compressed drums and the Leslie cabinet effect on Lennon’s voice, makes ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ a gear change moment in pop history.

“When I made my first tape loops, man was it a buzz!” McCartney told Wired magazine in 2011. “Bringing tape loops into the studio as I did, finding out that John has got a really funky tune called ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ that needed a solo…. Well, what was better than the crazy stuff I was doing?”

It was around this time that McCartney visited Peter Zinovieff’s electronic music studio in his back garden in Putney (Macca later misremembered this as a visit to the Radiophonic Workshop) where he was shown around the stacks of austere-looking oscillators, filters and tape machines by Delia Derbyshire, who was then collaborating with Zinovieff and fellow Radiophonic Workshop moonlighter Brian Hodgson as part of Unit Delta Plus. Unit Delta Plus went on to work with The Beatles (again it was McCartney who drove the project) on a couple of pieces of tape music for the Million Volt Light and Sound Rave in early 1967. One piece, ‘Carnival Of Light’, is a legendary slice of Beatles folklore, which remains unreleased to this day. Zinovieff proceeded to start the synth company EMS and give the world the VCS3 synthesiser, destined to become loved by the likes of Pink Floyd, Brian Eno and Conrad Schnitzler in the early 1970s, while Paul and The Beatles continued their adventures in sound.

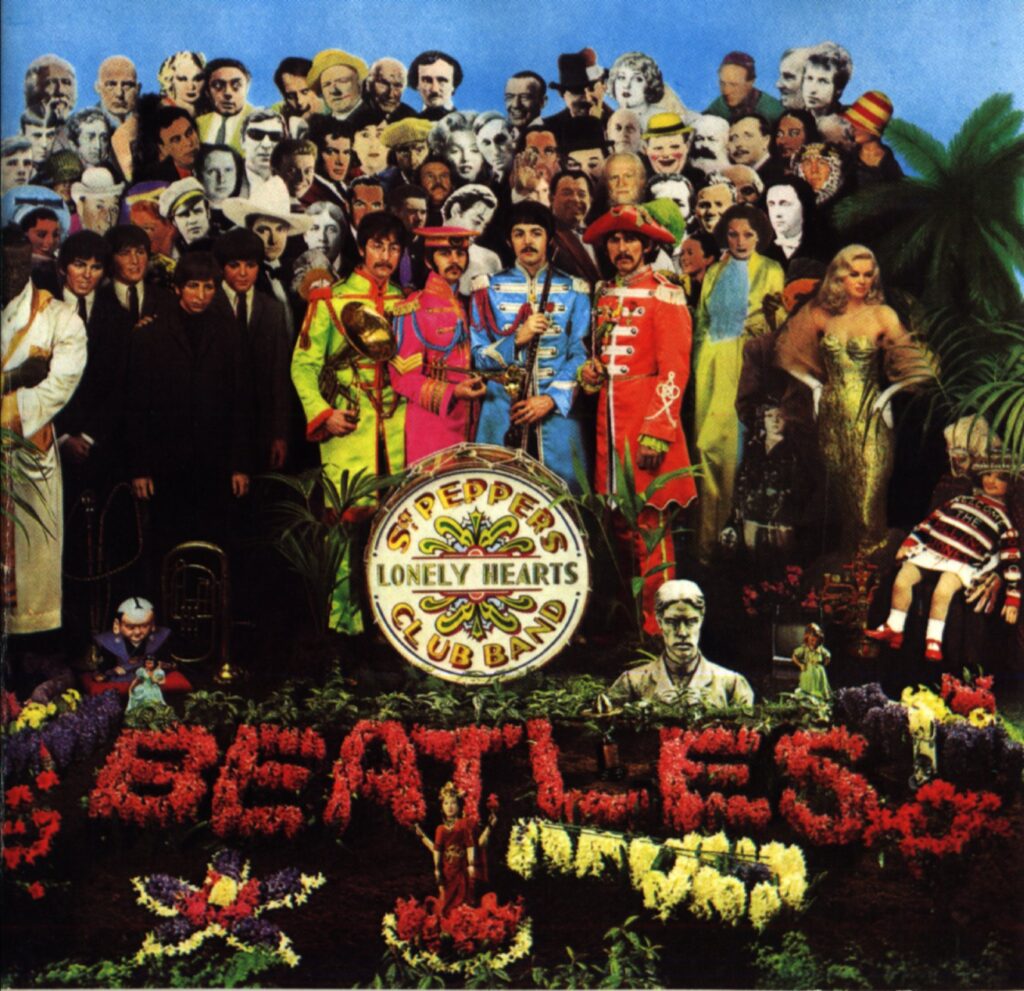

June 1967

The Beatles

‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’

(Parlophone)

With ‘Revolver’ at the top of the charts and August 1966 marking the end of The Beatles as a touring band (their final gig was in San Francisco, August 29, 1966), the band started work immediately on the next musical statement. The first recordings were for a single, Paul’s ‘Penny Lane’ and John’s ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’. The single served as a pretty solid indication as to what was to come next. A Mellotron provided the wistful intro to ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and backwards tapes were used to swell the rhythm track and introduce a sense of psychedelic wooziness, and the whole thing faded out, only to come back in with a loop of flutes over Ringo’s pseudo military beat, a disembodied voice intoning the words “cranberry sauce!” (or “Paul is dead!” if you were a half-deaf stoned conspiracy theorist).

It was released in February 1967, and softened up the nation for what was to come next. ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ took ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ as a starting point and flew off into previously uncharted sonic territory with spectacular results. The album took many techniques of musique concrete and assimilated them into an era-defining pop album. A clue was posted on the cover art, one of the 60-odd heroes and villains The Beatles gathered for their group shot was Stockhausen, chosen by Paul, top row, fifth from the left.

Taped sound effects are weaved into songs, like the crowd on the opener ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’; loops of fairground organs are used on ‘Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite’; there are more effects on ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’ and stray sounds (is that a chicken just before Paul’s count-in on ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club (Reprise)’?). The sonic textures of a decaying orchestral chord are given centre stage at the end of the album’s crowning song, ‘A Day In The Life’, and the whole shebang ends with a locked groove of gibberish, introduced by what sounds like grainy sine wave test tone.

In terms of its sheer reach, that locked groove snippet is probably the most widely heard piece of musique concrete ever made, more successful and surprising than the eight-minute piece on the next official Beatles album, 1968’s ’The Beatles’ (more widely known as ‘The White Album’), the often-skipped and much-maligned tape music piece ‘Revolution 9’ which was put together mostly by Lennon and Yoko Ono, with some input from George Harrison. The Beatles dominated the 1960s and beyond exploring and defining the possibilities of pop music, including electronic music, as they went along. No one matched their capacity for making such adventurous sounds so very popular.

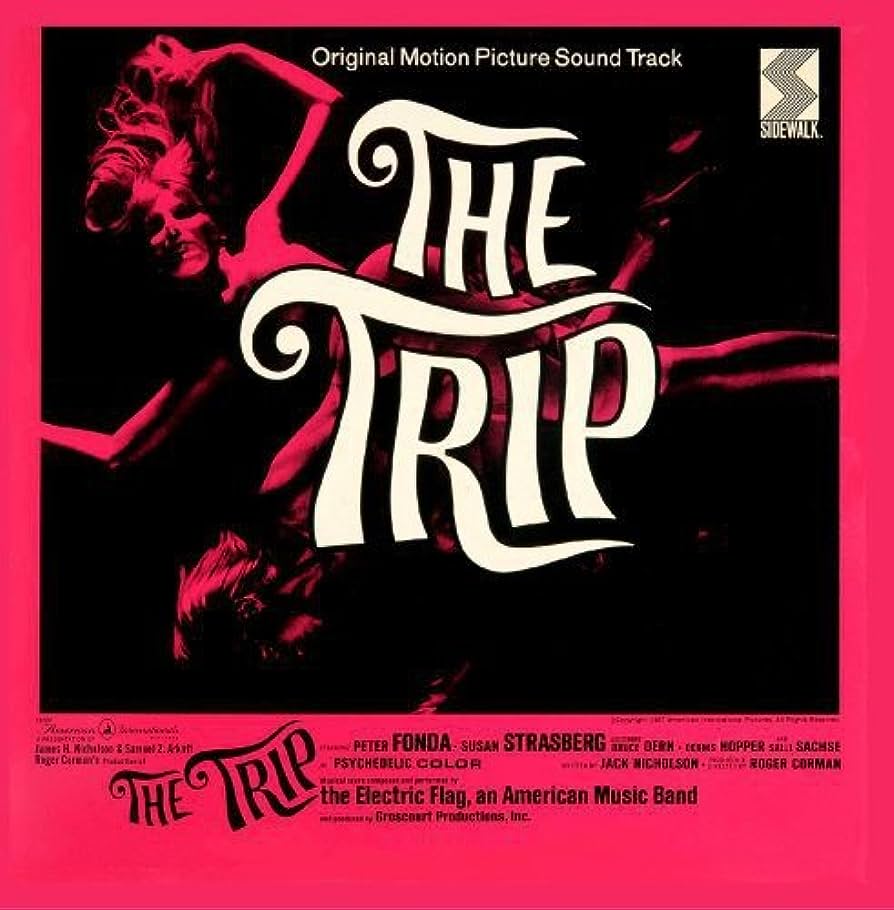

September 1967

The Electric Flag

‘The Trip’

(Sidewalk)

One of the first recordings featuring the Moog synthesiser, ‘The Trip’ was the soundtrack album for a Roger Corman LSD-inspired movie of the same name (“A Lovely Sort of Death” the poster proclaimed). The Electric Flag were actually a blues rock band who were hired to crank out enough tunes of the required bluesy-rocky-trippy stripe for Corman’s B-movie.

The band’s leader, Mike Bloomfield, hired Paul Beaver to add some Moog textures to a couple of tracks, and the soundtrack overshadowed the film by some margin. Although only two tracks featured Beaver’s work, the proto-krautrocker ‘Flash, Bam, Pow’ and ‘Fine Jung Thing’, the album is a landmark of electronic music.

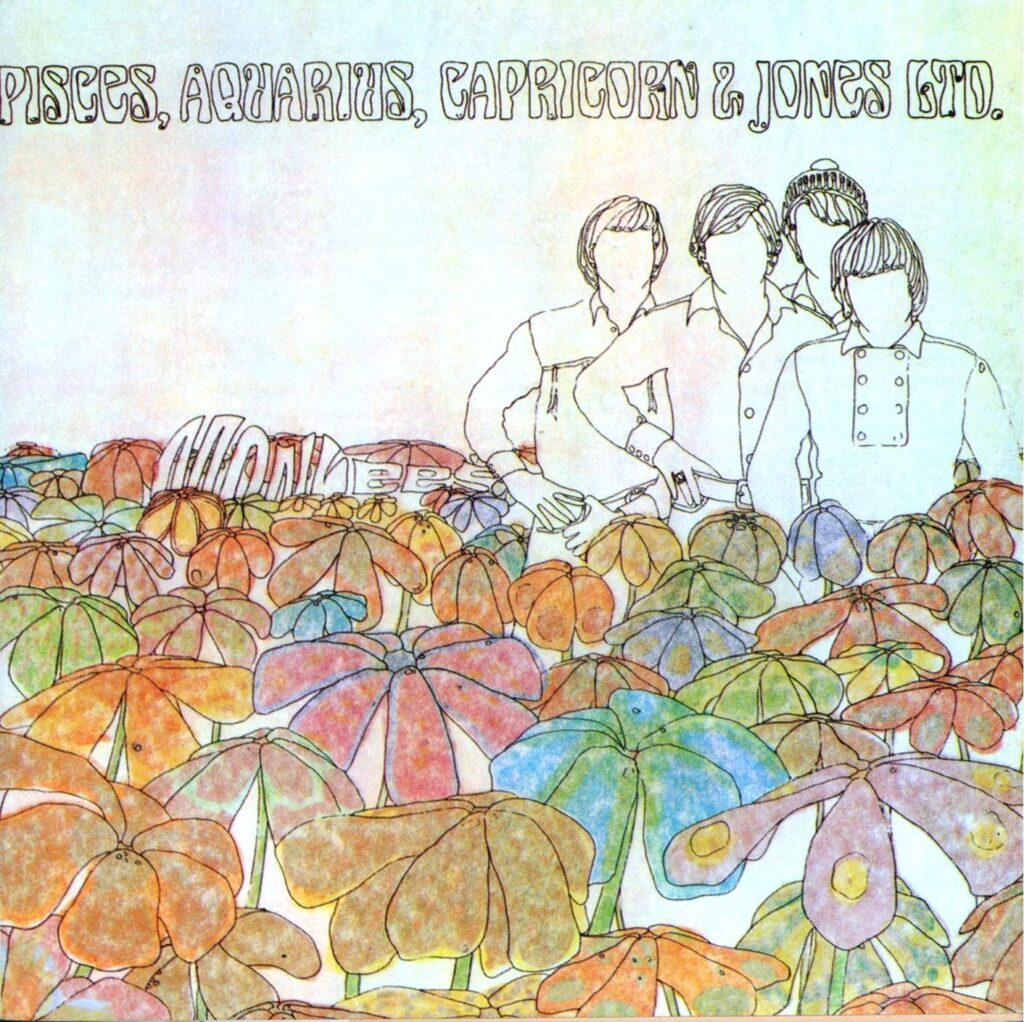

November 1967

The Monkees

‘Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd’

(Colgems)

In which the pre-Fab Four out-innovated their role models by slapping a Moog on a couple of tracks a full two years before George Harrison’s Moog modular made it on to the ‘Abbey Road’ album. Again, it was Paul Beaver who was called in to help make ‘Daily Nightly’ and ‘Star Collector’ suitably synth-freaky. This album, almost solely on the basis on the popularity of the band, probably did more to introduce the synthesiser to the general public than any other, until Wendy Carlos showed up a few months later, especially since the synth made an appearance on The Monkees’ weekly TV show with huge worldwide viewing figures.

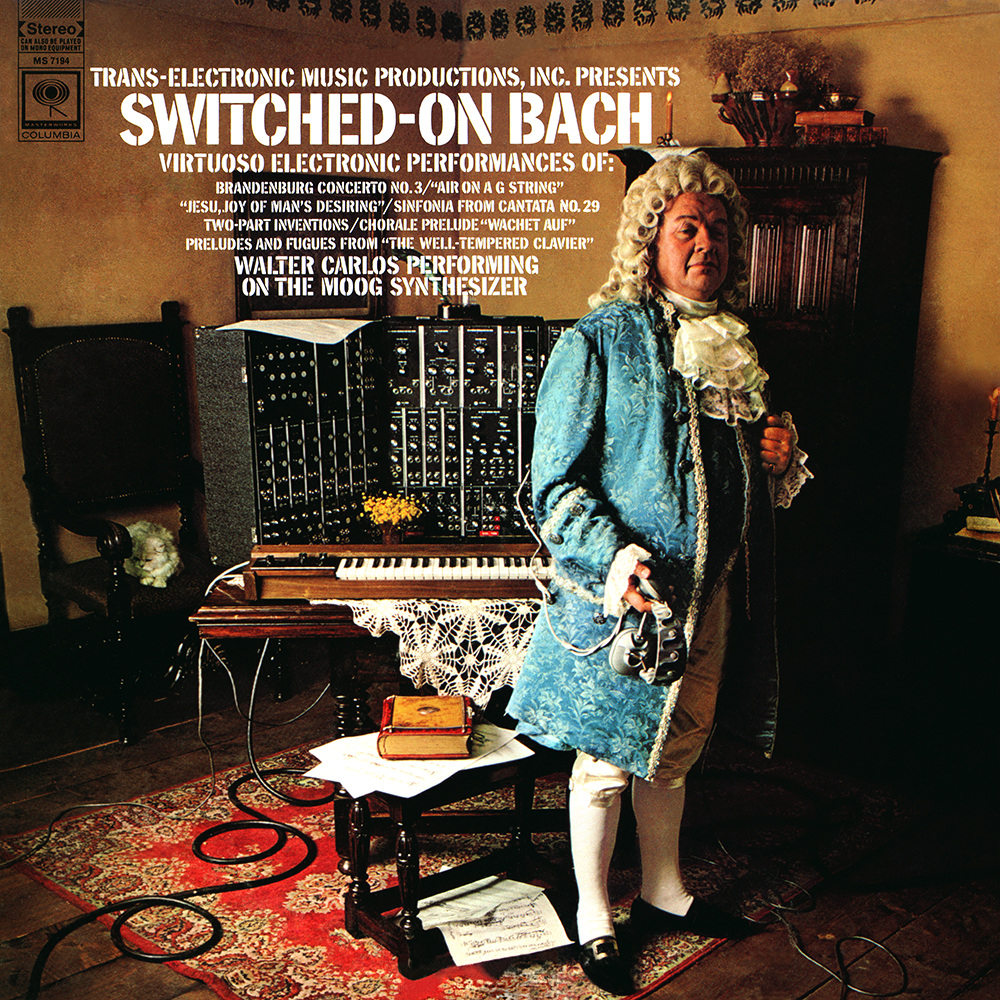

March 1968

Wendy Carlos

‘Switched-On Bach’

(Columbia)

In 1967, Robert Moog met Wendy Carlos, a recording engineer at a New York recording studio who was to become an early and enthusiastic customer of Moog products and would provide crucial feedback. It didn’t take long for Carlos to produce a tour de force of synthesiser virtuosity with Moog’s products.

“CBS had no idea what they had in ‘Switched-On Bach’,” Moog told Mark Vail, author of ‘Vintage Synthesizers’. “When it came out, they lumped it in at a studio press party for Terry Riley’s ‘In C’ and an abysmal record called ‘Rock And Other Four Letter Words’. Carlos was angered by this and refused to come. So CBS, frantic to have some representation, asked me to demonstrate the synthesiser. I remember there was a nice big bowl of joints on top of the mixing console and Terry Riley was there in his white Jesus suit, up on a pedestal, playing live on a Farfisa electronic organ against a backup of tape delays. ‘Rock And Other Four Letter Words’ went on to sell a few thousand records. ‘In C’ sold a few tens of thousands. ‘Switched-On Bach’ sold over a million and just keeps going on and on.”

Carlos went on to produce a few more classical-on-synths albums, before serving up her soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film, ‘A Clockwork Orange’, which signposted a new darker future for popular electronic music. It was this foray into strange and unsettling electronic sounds for a cult film, including her composition ‘Timesteps’ and her update of Beethoven for the ‘Theme From A Clockwork Orange’. She also reworked the fourth movement of Beethoven’s 9th symphony for the movie – which Kraftwerk adopted as intro music on their ‘Computer World’ world tour – and in doing so sealed her place as an inspiration to a generation of underground electronic musicians.

March 1968

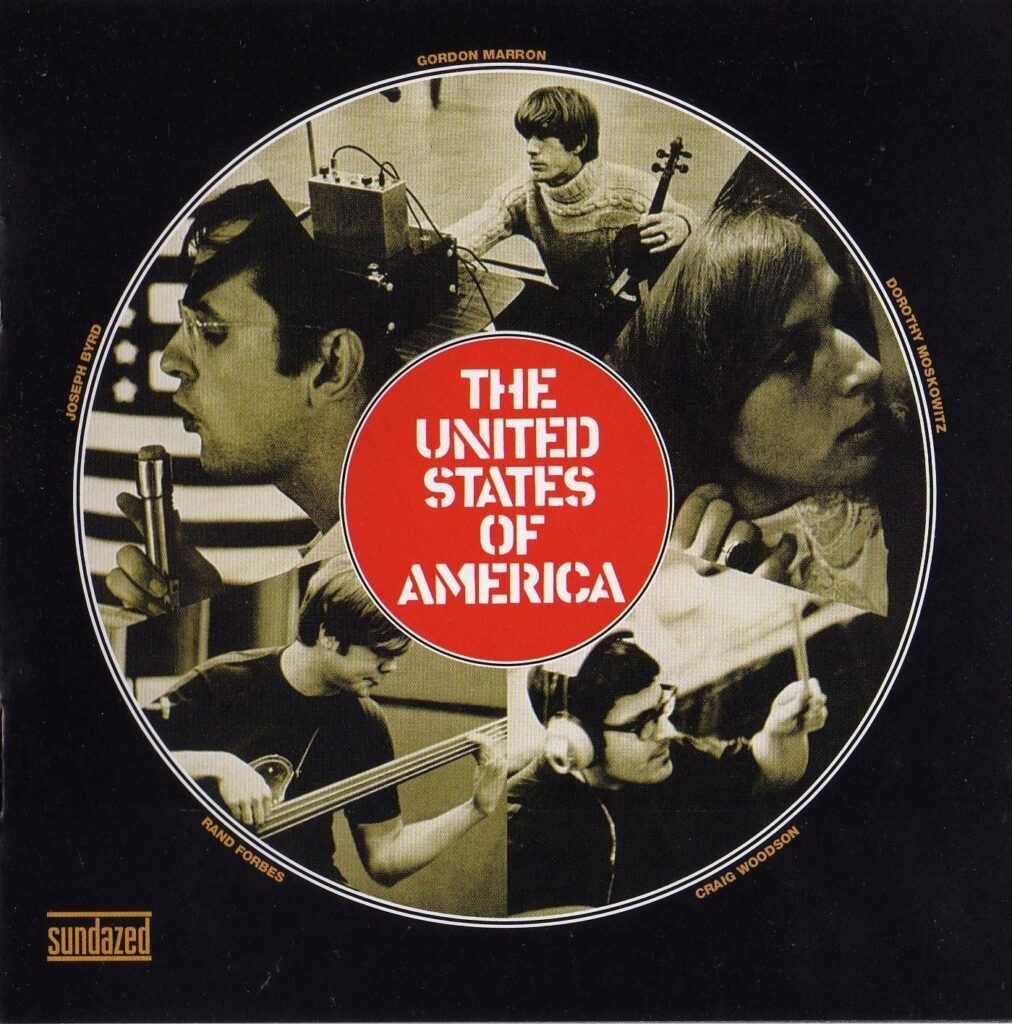

The United States Of America

‘The United States of America’

(Columbia)

Joe Byrd’s stated intent with his experimental rock band The United States of America was to combine electronic sound, musical and political radicalism and performance art. To the modern ear, it seems quite like Syd-era Pink Floyd with the special effects amped up to the max, and gets especially interesting when the electronics overwhelm the hippy song-smithery. The album sank without leaving too much evidence of it ever having existed, the band splitting up fairly acrimoniously very shortly after its release.

But in its political radicalism and its electronics, there was something of a blueprint for bands that came a decade later in the UK. The racket and confrontational noise pre-dated the likes of Throbbing Gristle (TG’s Genesis P-Orridge had some 1960s radicalism in his make up, being that bit older than many electronic contemporaries), signposting a more fractious future for electronic music’s assimilation into pop.

April 1968

Beaver & Krause

‘The Nonesuch Guide To Electronic Music’

(Nonesuch)

Beaver and Krause were put together by Jac Holzman of Elektra Records. Holzman was interested in the developments in electronic music and was following a hunch that something big would come out of it. Their first album as Beaver & Krause was essentially a technical showcase for the Moog modular they were using. It was a calling card for the duo, who would go on to produce their own electronic music albums (with actual songs, rather than technical explorations), and become electronic consultants to the superstars of the day. Although it was released in 1968, the album had been a work in progress from 1967, when the pair demonstrated the Moog Modular III system at the Monterey Pop Festival, which could be seen as the moment that the synthesiser met the pop mainstream.

June 1968

Silver Apples

‘Silver Apples’

(Kapp)

The duo of Simeon and Danny Taylor were an almost wholly anomalous entity in the rock scene of late 1960s. Simeon played a positively dangerous Heath Robinson-esque collection of oscillators and filters with his hands, feet and elbows (it nearly killed him more than once with electric shocks), while he sang in an unusual keening voice about oscillations and vibrations and the drums kept up a pace of jazz-inspired rock beats.

It was hairy and weird enough for the freaky vibes of the day and the pair landed a deal with small label Kapp. It’s music that would fit in a treat these days, and indeed Simeon, after a pretty long hiatus, returned to playing live in the 1990s with a new Silver Apples line-up. Danny and Simeon reunited for a few gigs in the 1990s once Simeon tracked him down, but Danny died in 2005.

The two albums Silver Apples made are an important part of the electronic music canon, languishing ignored for years until the group’s trailblazing commitment to their art was rediscovered and appreciated all over again, with Simeon collaborating with Portishead and as Silver-Qluster with Roedelius. Not to be confused with the 1968 Morton Subotnick album ‘Silver Apples Of The Moon’, another electronic music milestone which, while coming from an academic tradition, is quite accessible. “I got the name Silver Apples from a poem of Yeats, ‘The Song Of Wandering Aengus’,” Simeon said. He had never heard of Morton Subotnick, who also was referring to the Yeats poem when he named his LP. So that clears that up, then.

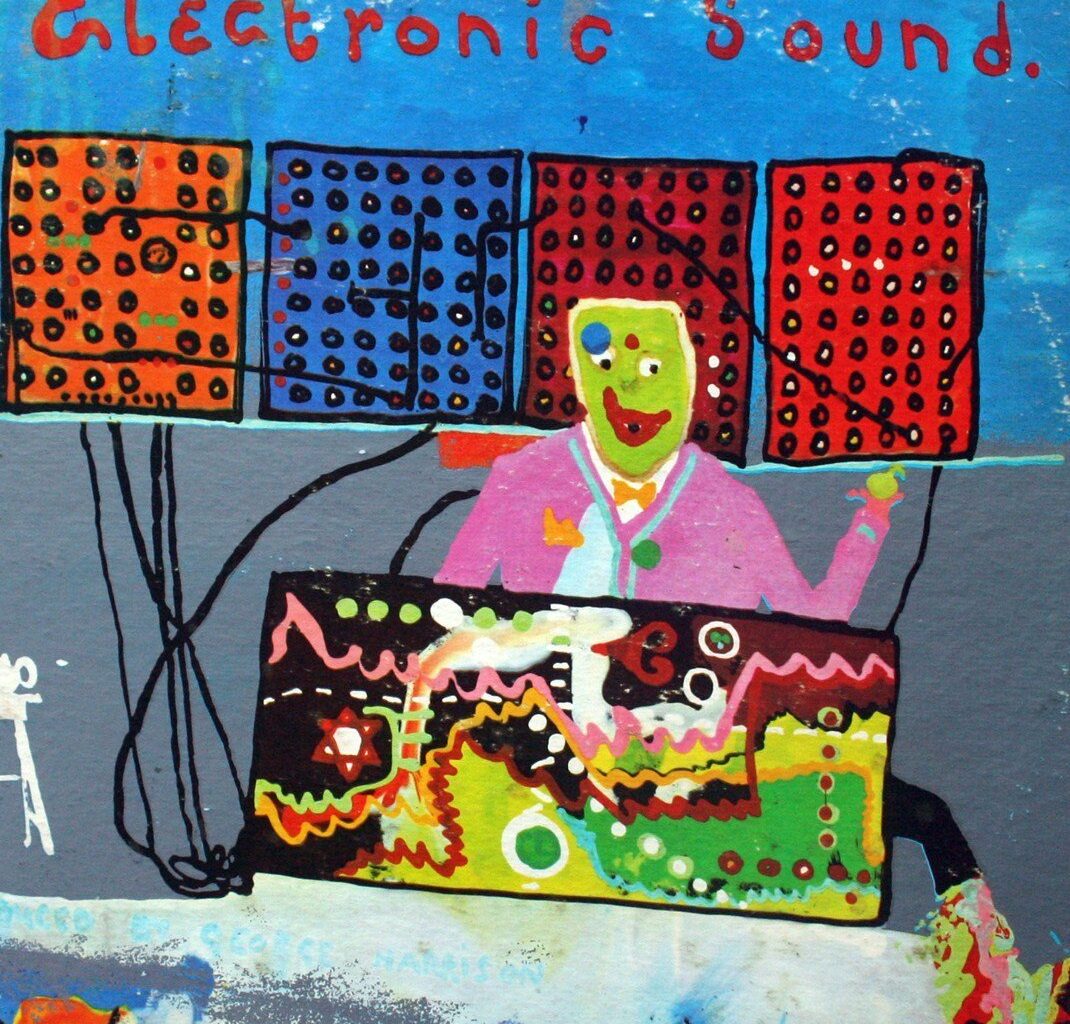

May 1969

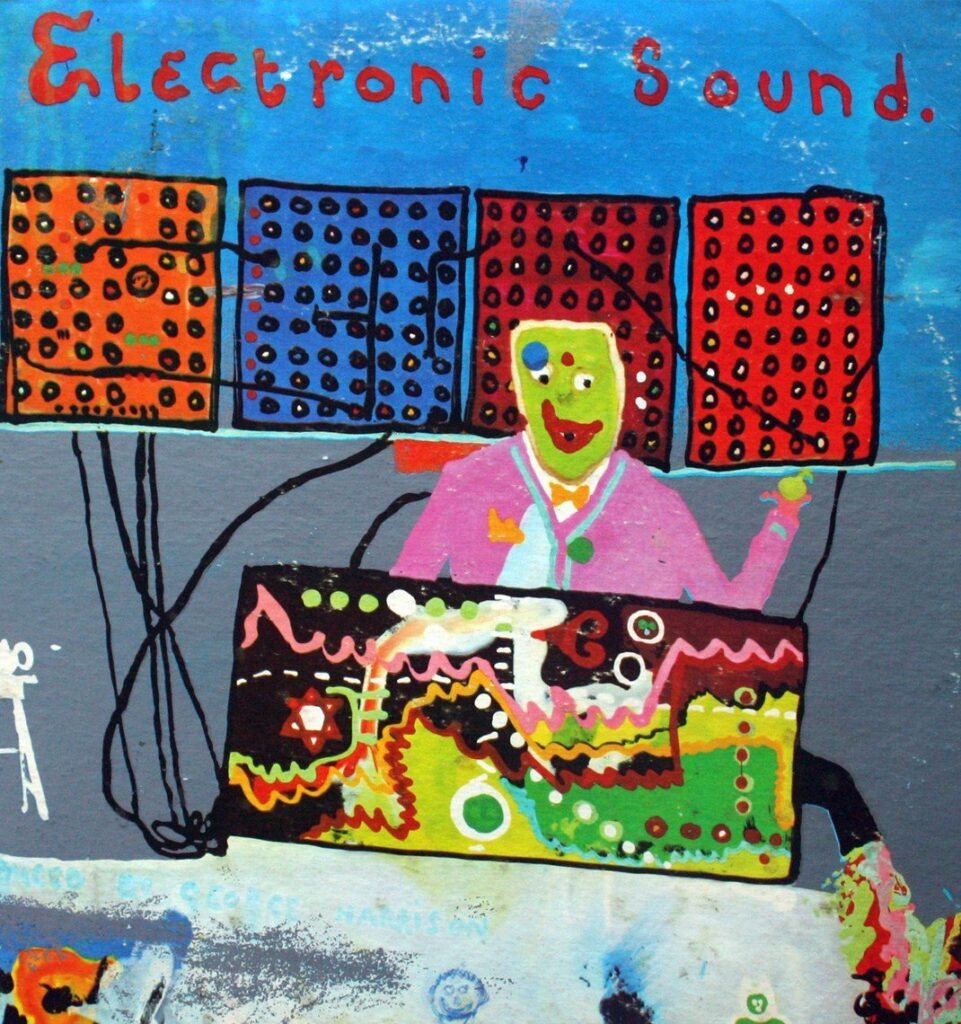

George Harrison

‘Electronic Sound’

(Zapple)

America was leading the way in electronic music in the 1960s. Bob Moog was building his modular systems and, in 1969, the patent he had filed for his low pass filter some years before was granted. The word Moog was, like Hoover, synonymous in most people’s mind with the very idea of electronic music; electronic music was Moog music, and thanks to the promotional efforts of Beaver & Krause it was gaining traction.

The ultimate endorsement could only come form one source at this point in pop history: The Beatles. George Harrison was in Los Angeles at the end of 1968, producing the debut album for new Apple signing Jackie Lomax, Bernie Krause was brought in with his Moog III modular system. Harrison asked Krause to stay on after the session and show him around the complicated machine. Harrison, without Krause’s knowledge, recorded the session.

Harrison, suitably impressed, bought a Moog III for himself and had it shipped to the UK where he toyed around with it, coming up with a piece he called ‘Under The Mersey Wall’ by overdubbing two Moog improvisations. Harrison bundled this with the recording he’d made in LA of the Bernie Krause demonstration (calling it ‘No Time Or Space’) for what became the second (and final) release on Apple’s experimental label, Zapple.

Krause wasn’t happy about his music being appropriated, but lacking the funds or the will to sue, he settled for having his name removed. Unsurprisingly, the album tanked on release, but Harrison’s Moog was used to much more melodic effect during the recording of the ‘Abbey Road’ album. It’s all over ‘Because’, ‘Here Comes The Sun’, and ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’ playing melodies and it also produces the white noise that engulfs ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’. Moog had arrived.

June 1969

White Noise

‘An Electric Storm’

(Island Records)

BBC Radiophonic Workshop employees Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson were often attempting to moonlight their way into a better payday then their BBC bosses were prepared to endow: this time it was with American musician David Vorhaus. They recorded an album of tape manipulations and electronic songs under the name White Noise, which became a cult hit, but it didn’t make enough money to keep Derbyshire and Hodgson on board. The album’s reputation has grown with time and is a classic in the development of the British electronic music.

September 1969

Gershon Kingsley

‘Music To Moog By’

(Audio Fidelity)

Running to just 25 minutes across its two sides, ‘Music To Moog By’ is a synthesiser cash-in cover versions album, including a couple of Lennon and McCartney numbers (‘Nowhere Man’ and ‘Paperback Writer’), traditional songs and originals by Kingsley, who had once worked with John Cage. The rather pretty cover featured a collage of a flower pot (cut from a photograph of the Moog modular) with the colourful leaves sprouting out of it made from photographs of nipples. It was all very 1969.

Kingsley was already known as an electronic composer, thanks to his work with Jean-Jacques Perrey (1966’s ‘The In Sound From Way Out’) and the Frenchman Perrey provided a connection between the American electronic music scene and the European tradition. Perrey was a friend of George Jenny, inventor of the Ondioline in 1941, and he had demonstrated this precursor of the synthesiser across France and the USA. ‘Music To Moog By’ was notable for the song ‘Pop Corn’, which was re-recorded and released as a single called ‘Popcorn’ by Hot Butter in 1972 when it became a huge international hit and introduced every Radio 2 listening suburban housewife to the pleasures of electronic music.

Gershon Kingsley went on to form the First Moog Quartet in 1970, intended to be a showcase for the Moog synthesiser in a live environment. They became the first group to perform electronic music at the prestigious Carnegie Hall in New York, and Kingsley has continued a career as a classical composer, ably demonstrated in the 2006 compilation of his religious music, ‘God Is A Moog’.

As an almost entirely irrelevant postscript, MP3s were circulating the internet for some time crediting ‘Popcorn’ to Kraftwerk. It just goes to show how the Düsseldorf foursome were synonymous with electronic music in many people’s minds, no matter what kind of electronic music it happened to be.

September 1970

Various Artists

‘Performance – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack’

(Warner Brothers)

The soundtrack album to Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammel’s psychedelic gangster film was dominated by the film’s star, Mick Jagger, with contributions from Randy Newman, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Ry Cooder, The Last Poets and the soundtrack’s composer Jack Nitzsche. However, Bernie Krause’s Moog work on the track ‘Performance’ – an unsettling looming bass note punctuated by slashes of white noise – is a crucial moment in pop history.

‘Performance’ is a very hip film which remained pretty underground after its release and as such became de rigueur viewing for any self-respecting pop culture magpie, many of who would latch onto the Moog sequence and squirrel it away for later reference. The powerful imagery and themes of ‘Performance’, together with these snippets of cold synthesised atmospheres, had an impact beyond cinema. You can hear echoes of it in the opening to Bowie’s ‘Station To Station’ and in the fearful, mood altering sounds Throbbing Gristle later unleashed, to name just a couple.

The Innovators

February 1974

Tangerine Dream

‘Phaedra’

(Virgin)

As far as the UK music press of the early 1970s was concerned, German synthesiser music, actually all electronic music, was all about “the Tangs”. Kraftwerk were yet to make much of an impression outside of their domestic underground post-beatnik crowd. ‘Phaedra’ was Tangerine Dream’s fifth album and their first for Richard Branson’s new Virgin label. Sales of the album were so healthy in the UK that, along with Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’, it actually kept Virgin afloat.

Tangerine Dream’s popularity was built on the kosmische stream of German electronic music; lengthy synth jams that suggested the vastness of space to their mind-blown listeners. But this version of Tangerine Dream had developed over four albums from less ordered experimental beginnings when the band was Edgar Froese, Klaus Schulze and Conrad Schnitzler. Schnitzler helped found the Zodiak Free Arts Lab in West Berlin with Hans-Joachim Roedelius. The Zodiak was a hub for avant garde artists and musicians and the early line-up of Tangerine Dream played there frequently. This was the genesis of the so-called “Berlin School” of electronic music; ambient, far-out electronic music that would evolve into new age, and ambient shapes, rather than the more strident and beat-reliant approach favoured in Düsseldorf.

Schnitzler left Tangerine Dream after one album and formed Kluster with Dieter Moebius and Roedelius, but soon set off to pursue a fascinating and idiosyncratic solo career instead, while Klaus Schultze went on to form Ash Ra Tempel with Manuel Göttsching, but also only managed one album before establishing himself as a solo artist. His extensive output of long atmospheric concept pieces is the Berlin School writ large. Manuel Göttsching, meanwhile, recorded the extraordinary album ‘E2-E4’ in 1984, an album whose anticipation of techno and house music styles is uncanny. The Tangerine Dream finally ended in 2015 when Edgar Froese passed away, aged 70, leaving a legacy of hugely important music.

December 1976

Jean-Michel Jarre

‘Oxygène’

(Disques Dreyfus/Polydor)

Jarre’s 1976 concept album (released in mid-1977 outside France) straddled the world of progressive rock and electronic music, a bit like Tangerine Dream. It was progressive in that it was a sophisticated series of movements bound together by a theme (intended as a ecological statement of some sort) and shared a classical music pretension with the likes of Yes, Emerson Lake & Palmer and Genesis, all of whom were keen synthesiser botherers.

However, Jarre had studied electronic music at Pierre Schaeffer’s Groupe de Recherches Musicales in Paris, an offshoot from the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète, which had been established by Schaeffer, Pierre Henry and Jacques Poullin and was effectively the home of musique concrete. Like Kraftwerk and their umbilical connection to the electro-acoustic pioneers of mid-century avant garde composers like Stockhausen, Jarre was similarly and more directly schooled by the theories of composers who helped shaped modern musical sound and even worked for a while with Stockhausen himself in Cologne.

Despite its largely lukewarm critical reception in the UK, ‘Oxygène’ eventually sold 15 million copies and Jarre went on to stage ever more lavish live productions of his electronic opuses in unusual locations throughout the world, peddling a kind of electronic music Las Vegas-style spectacle to huge crowds, arriving as middle England’s favourite electronic music Frenchman when the Mail On Sunday gave away two million copies of ‘Oxygène’ as a cover mount in 2008. Recently, his ‘Electronica 1: The Time Machine’ album marked a return to his electronic roots and spawned a set of collaborations more interesting than most of his other post-‘Oxygène’ output.

November 1974

Kraftwerk

‘Autobahn’

(Phillips)

Kraftwerk’s fourth album was the first to reach a wide audience. It was partly thanks to the edit of the title track (down to three minutes from 22 minutes), which enabled its acceptance as a novelty pop single and therefore extensive radio play. But the success was really down to the fact that ‘Autobahn’ had a beautiful synthetic and melodic fluidity and a witty and easily remembered “chorus”.

Despite being sung in German, it sounded enough like a Beach Boys spoof to find receptive ears in the USA where it became a hit. It’s difficult to overstate the importance of this moment, not least because it led to another four peerless Kraftwerk albums, at least two of which (‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ’Computer World’) became holy books of entire genres. Not only that, but behind Kraftwerk’s breakthrough moment is an entire rich seam of German electronic music, from the grand figure of European electronic high art music, Stockhausen, to Neu! and beyond.

Thanks to their transistor radios, Stockhausen’s broadcasts from the Cologne Electronic Music Studio were part of the childhood soundscape of Ralf and Florian (and Wolfgang Flür and Karl Bartos) and his ideas were internalised and expressed in their pre-‘Autobahn’ output, not least because their producer, Conny Plank, had worked with Stockhausen quite extensively. Plank was coldly ditched by the group after ‘Autobahn’, but their work with him provides a further connection between Kraftwerk and Neu!, whom he also produced – after all, both Neu!’s Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger had been in an early line-up of Kraftwerk.

When Eno went seeking out the fresh sounds of German electronic music, he entered Plank’s world and it spawned collaborations with Cluster’s Dieter Moebieus and Hans-Joachim Roedelius and the sound canvas for Bowie’s ‘Low’ album, which itself was a pivotal record in the development of British electronic music. Plank was much in demand as time went on, producing and nurturing talent like Ultravox, DAF, Eurythmics, Echo & The Bunnymen, Einstürzende Neubauten and many more.

Kraftwerk’s latest incarnation as a long-running musical art gallery installation, selling thousands of tickets in record time all over the world does rather obscure the fact that they haven’t released any new material since 2001. The sole remaining founding member, Ralf Hütter, is now on a slowly atrophying mission of refinement and legacy management.

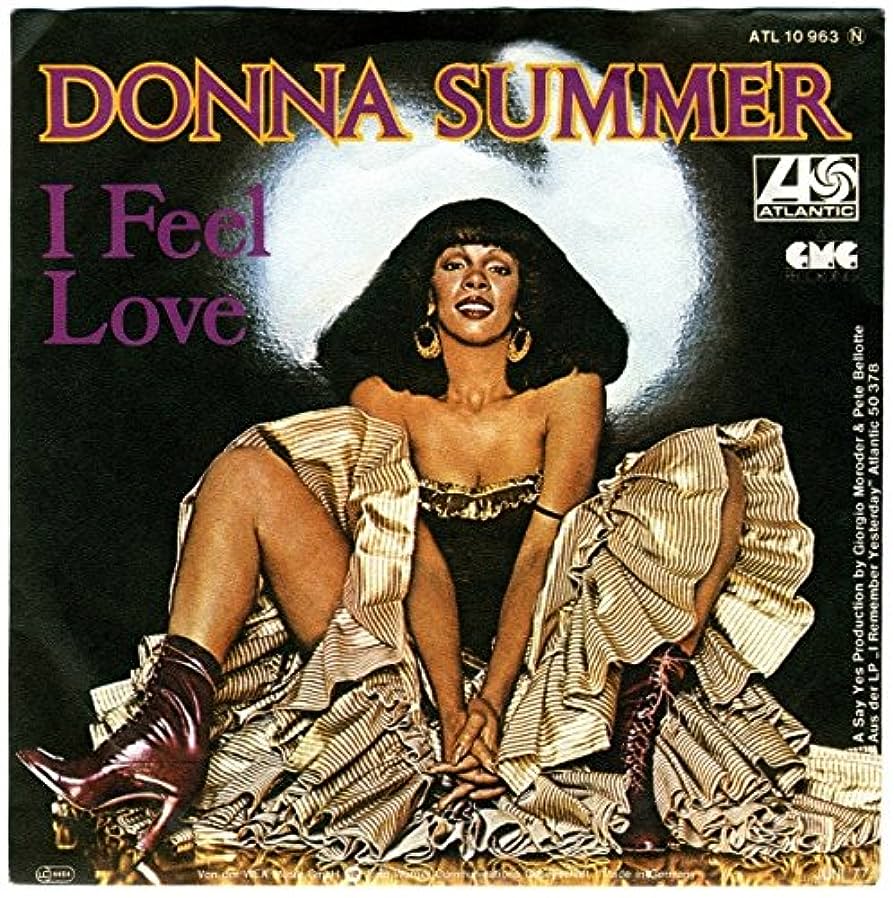

July 1977

Donna Summer

‘I Feel Love’

(Casablanca/GTO)

Donna Summer’s “I had no idea what it was actually about” protests aside, ‘I Feel Love’ was a glorious hymn to delirious sex aimed squarely at the dancefloors of Europe and America. It dealt disco a hefty slap on the buttocks, propelling it into the thumping four-to-the-floor territory that would come to dominate club music, predicting the hard and dark edge of techno and house.

It’s a tune so huge and familiar, it’s easy to forget just how beautifully produced it is; the machines being teased into providing new textures every few measures, repetitive but constantly shifting timbres from the bassy depths of the Moog modular system. It was a huge leap forward for electronic music. It’s every bit as important as any Kraftwerk from the same period. In fact, the similarity between ‘I Feel Love’ and Kraftwerk’s ‘Spacelab’ from ‘The Man-Machine’ (released a full year after ‘I Feel Love’) was certainly noted at the time.

The whole approach of the pulsing machine sequence is what any studio producer would now call ‘Moroder-esque’. “Kraftwerk? Well, I think they thought that they must start selling more,” responded Moroder at the time in an NME interview. “I guess they are making a simple mistake. They still reckon that with an easy melody and a synthesiser they can have a hit.”

Moroder’s work lacks the intellectual heft of Kraftwerk, but he was later lionised by Daft Punk on ‘Giorgio By Moroder’ on the 2013 album ‘Random Access Memories’, a documentary song created to celebrate his contribution to the dancefloor.

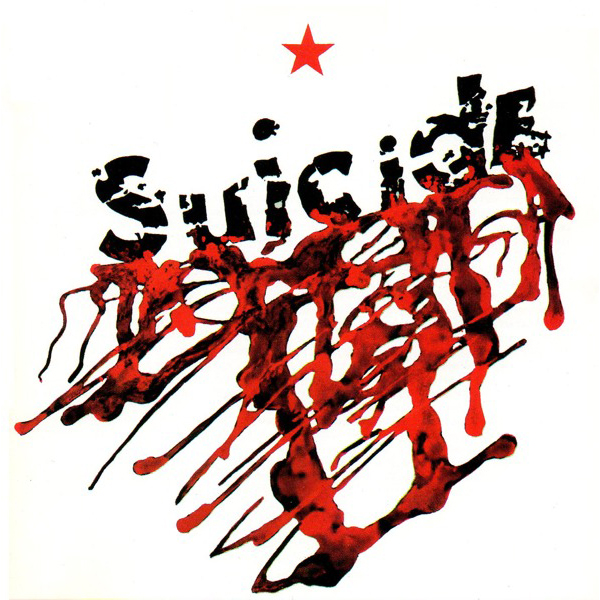

December 1977

Suicide

‘Suicide’

(Red Star)

Suicide were an essential component of the New York post-punk scene, the scuzzy punk partnership of vocalist Alan Vega and Martin Rev whose raw electronic backing music was the result of grabbing the cheapest, crappiest gear that was almost being given away in small ads; poverty was the driving necessity behind their aesthetic.

They were regulars at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City, cohorts of Blondie, Devo, Talking Heads, Television, The Ramones, and had been gigging for five years before the stars aligned and the world was ready for their brand of intense machine music on vinyl. It was part edgy rock ’n’ roll, part krautrock, part psychedelia and wholly punk rock, thanks to its clear identification with society’s underdogs and the atmosphere of tension and confrontation, even on the more tuneful tracks like ‘Cheree’.

The album’s standout is ‘Frankie Teardrop’, a partly improvised story of desperation, murder and suicide inspired by a newspaper story Vega had read, set to Rev’s droning one-key backing, laced with echo explosions, screams and found sound. ‘Frankie Teardrop’ has the unusual distinction of having directly influenced both Bruce Springsteen and Spacemen 3. The album was better received in the UK than in America at the time (Rolling Stone’s hostility to new music that was light on guitar solos was causing a real blockage in American music criticism) and is now firmly ensconced in the top-albums-of-all-time firmament.

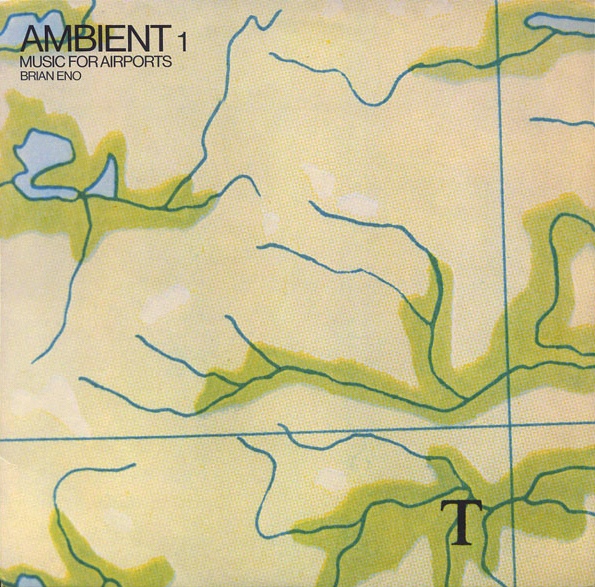

March 1978

Brian Eno

‘Ambient 1: Music For Airports’

(EG)

From attending a talk at art school in the 1960s given by The Who’s Pete Townshend on the use of tape machines for non-musicians which inspired him to start making music, and then crashing into British living rooms in 1972 when he was seen manipulating an EMS VCS3 on ‘Top Of The Pops’ as a member of Roxy Music, performing their hit ‘Virginia Plain’, Eno’s contribution to the shape of contemporary music is almost immeasurable.

Like David Bowie, Eno’s antennae were finely tuned to pick up what was essential in the new music being produced in Europe and America. His fulsome praise of Michael Rother’s post-Neu! band Harmonia and their January 1974 debut album ‘Musik Von Harmonia’ (“the world’s most important rock band”) helped propel it to the UK’s record buying public who might have otherwise missed it. The statement was the start of his lengthy flirtation with Germany’s un-rock aristocracy and led to his 1976 recordings with Harmonia (though the results weren’t released until the 1990s as ‘Tracks And Traces’) and a fruitful love affair with Moebius and Roedelius, the immediate progeny of which (‘Cluster & Eno’ in 1977 and ‘After The Heat’ in 1978) were almost as influential as the electronic work he contributed to Bowie’s ‘Low’ album.

In 1977, Bowie and Iggy Pop “discovered” Devo (a demo tape was pressed into their hands during Iggy’s ‘The Idiot’ tour when it pulled into Cleveland, Ohio), and when Bowie couldn’t fulfil his promise to them to produce their debut album in Tokyo due to the 800 other things he was committed to, Eno took over and produced it at Conny Plank’s studio outside Cologne. Devo’s ‘Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!’ and the ‘No New York’ compilation album of noise bands were released in 1978, along with the first of three Eno-produced Talking Heads albums. In 1979, Eno and Talking Heads frontman David Byrne started recording what became the masterpiece of commercial experimental electronic music, ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’ (although it wasn’t released until 1981).

If you throw a pebble into a pile of all the interesting albums released in the 1970s, there’s a very good chance it will hit one with Eno’s name on it. ‘Ambient 1: Music For Airports’ is particularly interesting because it gave birth (and a name) to a genre which would, for better or worse, be with us from that moment on, and splinter into various sub-genres like illbient and chillout. But it stands as a marker for Eno’s place as the primary producer/collaborator of the age.

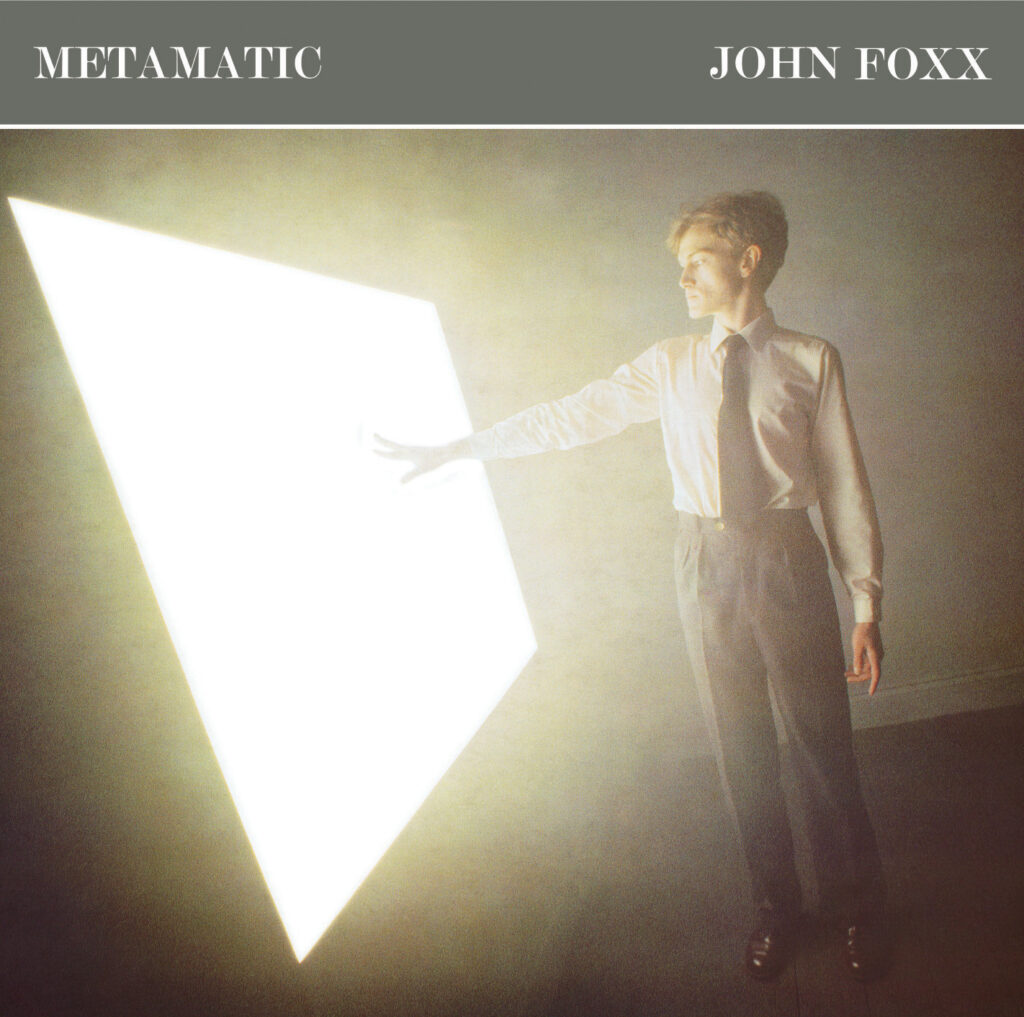

January 1980

John Foxx

‘Metamatic’

(Virgin)

Postponed from 1979, John Foxx’s first solo outing after his many productive but ultimately frustrating years with Ultravox remains a high-water mark of minimal wave synthesiser work. As the first synth album of the 80s, its tone wasn’t the one that would carry forward to define its epoch – that job was done by the Human League’s ‘Dare’ and Depeche Mode’s upbeat bounciness – but ‘Metamatic’ nonetheless caught a mood that continued as a constant undercurrent for decades to come.

Its standout moment is ‘Underpass’, but the album is filled with magical moments of dark strangeness. The opening, ‘Plaza’, sets out the stall: “On the plaza / We’re dancing slowly lit like photographs”. It’s a masterclass of hallucinatory dystopian images weaved into fleeting and sparse musical pieces; they come and go like shadowy figures leaving the scene via brutalist architectural walkways. In plucking this series of vignettes from the concrete gloom of London’s edges, ‘Metamatic’ created a blueprint for decades of plunder by generations of electronic dismalists.

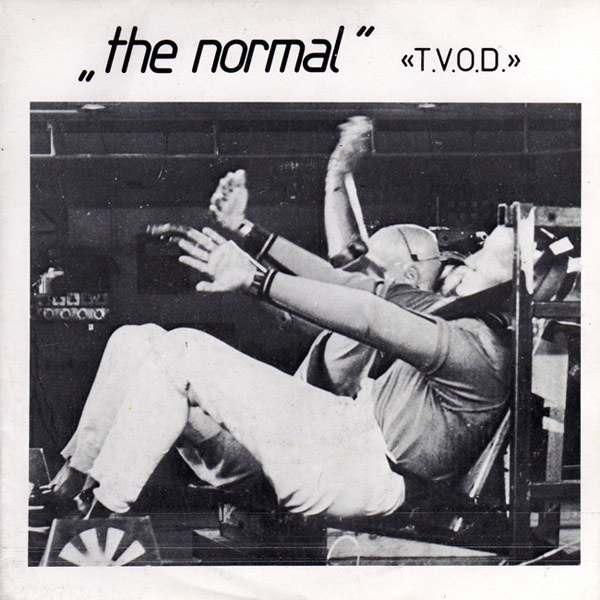

November 1978

The Normal

‘TVOD’/‘Warm Leatherette’

(Mute)

In which a label is born, helmed by an electronic music freak, Daniel Miller, whose early exposure to Kraftwerk while on a gap year driving around Germany in 1974 flourished into perhaps the most successful and important record label in British, arguably worldwide, electronica.

This is the label that gave the world Depeche Mode, probably the best-selling electronic band in the world, and introduced huge swathes of important electronic music to the listening public. Fad Gadget, Einstürzende Neubauten, Nitzer Ebb, Laibach, Renegade Soundwave, Die Krupps, Moby, Add N To (X), Goldfrapp, Luke Slater, Polly Scattergood: all Mute artists. Even Can and Kraftwerk were released on the label, with Mute sub-label The Grey Area re-releasing Can’s back catalogue in the 1990s along with those of Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire and the Radiophonic Workshop… and the Kraftwerk remasters on Mute itself in 2009.

The Normal seven-inch, catalogue number Mute 1, with its austere black and white imagery of crash test dummies and neo-modern computer display Letraset type, the band name bookmarked by oddly positioned quote marks, gave the release a mysterious and European feel. ‘Warm Leatherette’ was famously influenced by JG Ballard’s novel ‘Crash’ and nudged the synth/sci-fi axis into a more literary and intellectual orbit, away from Mozart in space and more towards ‘A Clockwork Orange’. ‘TVOD’, meanwhile, presaged the modern age of mainlining media via our iDevices (“I don’t need no / TV screen / I just plug the aerial / into my skin’) and was released a full five years before David Cronenberg’s film ‘Videodrome’, which dealt with similar themes of queasiness around the impact modern media was having on humanity.

In an unexpected turn of events for an underground and forbidding synth-punk seven-inch, ‘Warm Leatherette’ was covered by Grace Jones two years later and turned into a stripped funk workout. Jones’ taste for electronic landmarks was rehearsed again a year later when she covered ‘Nightclubbing’ from Iggy Pop’s ‘The Idiot’, which had already been tackled by The Human League on their ‘Holiday 80’ EP.

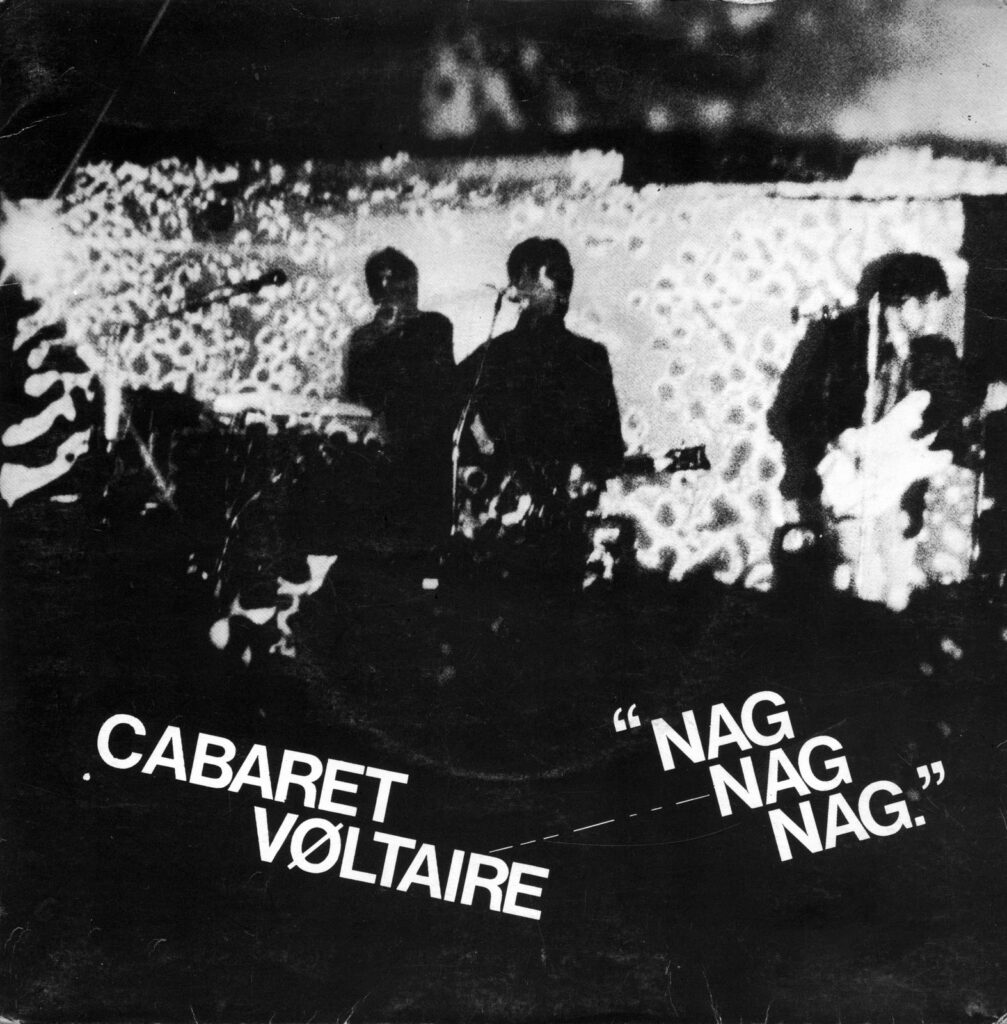

April 1979

Cabaret Voltaire

‘Nag Nag Nag’

(Rough Trade)

For Sheffield’s Cabaret Voltaire, the confrontational four-odd minutes of distortion, white noise and angry vocals that sounded like the amplified thoughts of a raging pyschopath building up to a violent meltdown, aka ‘Nag Nag Nag’, was a pop song. It opens with a tail of a tape echo that fades into an impossibly thin and distorted guitar riff accompanied by a teeth-gratingly intense rushing synth tone (it might be a guitar, it might be a manipulated tape recording of white noise off the telly, anything was possible in the Cabs’ soundworld) which pretty much runs throughout the entire song.

It’s an electronic music classic that was as influenced by garage punk of the 1960s as it was by the likes of Can and Kraftwerk. “‘Nag Nag Nag’ was a one-off,” Stephen Mallinder (Mal) told Electronic Sound. “We just sort of twisted that 60s psych rock thing into a northern electro version of it. It was our homage to that period.”

It was also the first time they’d recorded outside their Western Works studio in Sheffield, with Mayo Thompson of Red Krayola producing. “It was, ‘Oh wow, we’re actually making that connection with that 60s psychedelic garage thing’,” Mal remembers. The Cabs had been making music since 1973, dense experimental pieces of tape loops, cut-ups, samples and filtering, and continued in that vein until 1982 when they entered a new dancefloor-friendly phase. They managed to pull off modest commercial success without losing their reputation as an experimental and confrontational band and remain one of the UK’s most influential.

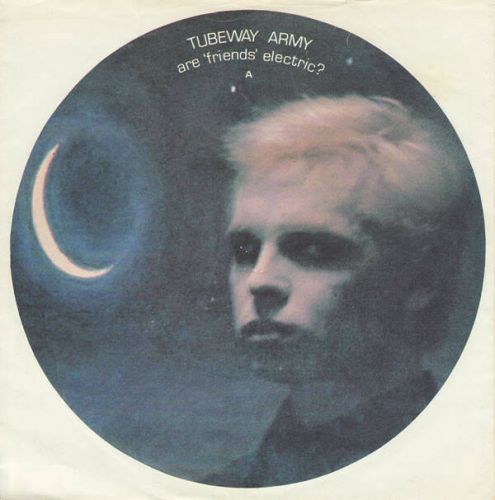

May 1979

Tubeway Army

‘Are “Friends” Electric?’

(Beggars Banquet)

The title is a riot of grammatical tics, what with the question mark and the quote marks, perhaps referencing ‘Heroes’ a bit too cheekily for some who would dismiss Numan as a Bowie copyist. The artwork was murky and foreboding, it was on a label associated with second tier punk like The Lurkers and eccentric outsider Johnny G, and the music… five and a half minutes of a beefy Moog bassline augmented with a bass guitar and very simple drums, a series of hollow synthesiser movements rather than a song as such. And then there’s the singing, Numan’s nasal whine, his sneer almost audible.

And what was it about? His “friend” has broken down? Oh, now we see why it’s in quote marks. Numan’s fuck machine has clapped out. And this is the single the British public sent to the top of the charts for four weeks. At one point it was selling 40,000 copies a day and spectacularly outperformed Bowie’s single of the time, ‘Boys Keep Swinging’. “I’ve seen some of his videos,” Bowie told Record Mirror in 1979. “To be honest, I never meant for cloning to be a part of the 80s. He’s not only copied me, he’s clever and he’s got all my influences too. I guess it’s the best of luck to him.”

The success of ‘Are “Friends” Electric?’ took everyone involved by surprise and would have long-lasting ramifications. Numan would outdo himself within the year with ‘Cars’ (Top 10 in the USA and another UK Number One) and its parent album, ‘The Pleasure Principle’, knocked Led Zeppelin’s swansong (sorry) album ‘In Through The Out Door’ off the top spot.

On 16 February 1980, his American success saw him appear on ‘Saturday Night Live’ and his sound was beamed into millions of American homes, and landed particularly heavily in New York and Detroit. Along with the output of Kraftwerk, ‘Cars’ became one of the founding cuts of hip hop. “Everyone was aware of him,” Afrika Bambaataa has said. ‘Cars’ was appropriated in 1989 by the Marley Marl-produced Kool G Rap & DJ Polo who gleefully altered the original intention of Numan’s lyrics with the car as the barrier against his paranoia and fear, by rapping “I drive a dope car!” and singing its praises as a girl magnet. You can hear a similar air and space that you find in Numan’s powerful synth work in Marl’s later bass-heavy hip hop productions with the likes of Lords Of The Underground; dark and empty, unsettlingly melancholy. Wu Tang Clan’s GZA filched ‘Films’ for a track from his 2008 album ‘Pro Tools’, and Numan has been namechecked by Juan Atkins and others as an important influence in the development of techno.

‘Telekon’ (another UK Number One LP) provided Trent Reznor with his daily dose of inspiration while recording his own genre-defining album, ‘Pretty Hate Machine’, closing a loop on Bowie who cited Nine Inch Nails as one his favourite bands in the early 1990s and had them as tour support. Numan divides opinion still, but there’s no doubt about it, he was the first electronic music superstar and his early success remains one of the most remarkable spectacles of the age.

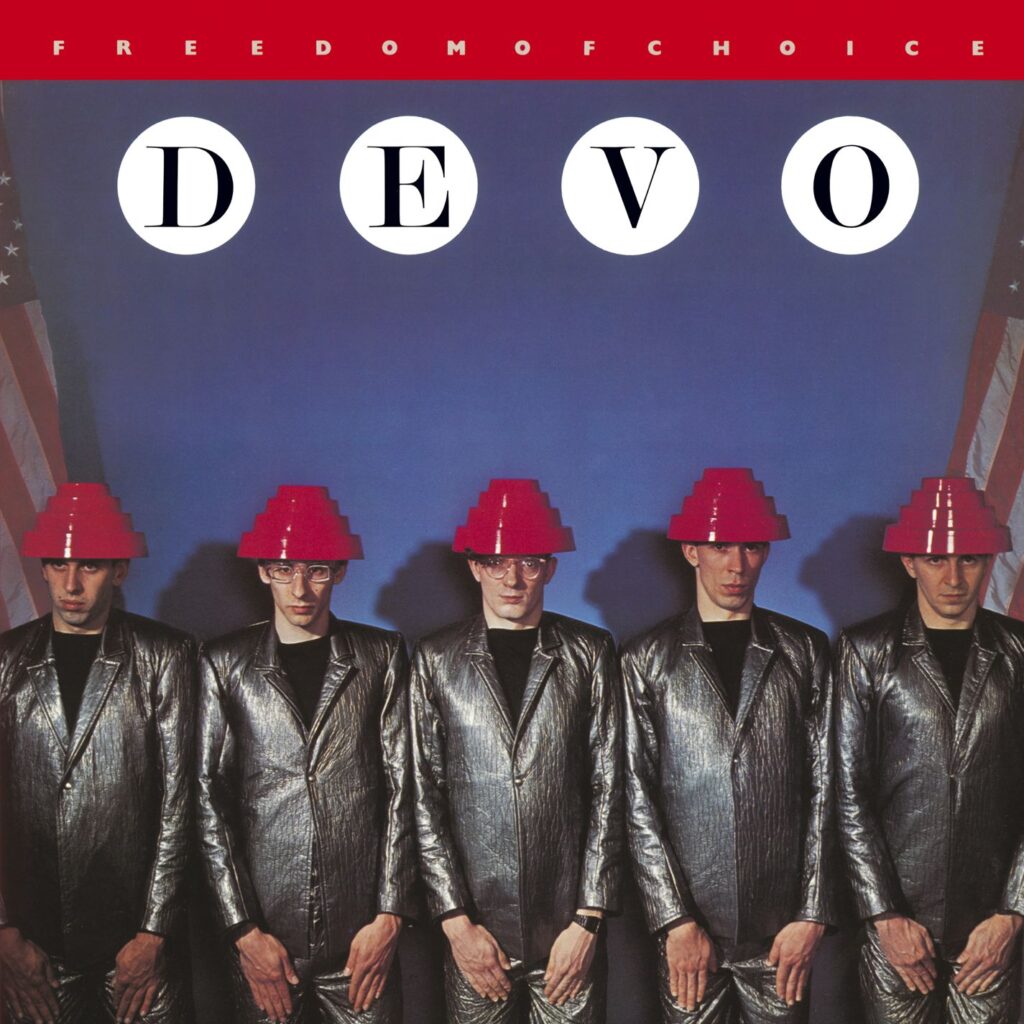

May 1980

Devo

‘Freedom Of Choice’

(Warner Brothers/Virgin)

America’s relationship with the synthesiser was more problematic than in Europe. The monolithic nature of American pop media (spearheaded by Rolling Stone who had already described Devo as “fascist clowns”) meant that resistance to the synthesiser usurping the guitar was fierce. This was the country that gave the world the “Disco Sucks” campaign after all.

And it was into this milieu that Devo released their third album, ‘Freedom Of Choice’. Having found a considerable cult following with their 1978 debut, ‘Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!’ thanks in no small part to the patronage of Bowie and Eno, the second album had been a bit of flop and Devo were in the last chance saloon when they went to make ‘Freedom Of Choice’. They all but ditched the guitars and the punkishness of their earlier records and let the synthesisers do the talking.

To produce, they hired Robert Margouleff, the man responsible for synth programming on Stevie Wonder’s ‘Innervisions’ and ‘Talking Book’, as well as Lothar And The Hand People’s ‘Presenting…’ in 1968, which was a curious hybrid of psychedelic rock and synthesiser. Margouleff had been one half of Tonto’s Expanding Head Band, who had built a legendary synth monster called the TONTO Synthesizer, put together from Moog modules and various bits and pieces from EMS, Oberheim, Yamaha, Serge, ARP, Roland and others.

“The release of Tonto’s Expanding Head Band was an inspirational indicator for starving Spudboys who had grown tired of the soup du jour,” wrote Devo frontman Mark Mothersbaugh in the liner notes to a 1996 re-packaging of Tonto’s Expanding Head Band’s material. ‘Freedom Of Choice’ is one of the very first synthpop albums of the 1980s, a tight collection of catchy and upbeat songs which somehow managed to simultaneously celebrate and satirise American culture. It gave Devo their first (and only) big hit, ‘Whip It’, etched their “upside-down flowerpot” headgear (it’s called an energy dome) into the popular culture consciousness of America and arguably overturned the nation’s resistance to synthpop in one fell swoop.

The Poppers

September 1979

The Buggles

‘Video Killed The Radio Star’

(Island)

“They took the credit for your second symphony / Rewritten by machines with new technology,” sang Trevor Horn, chief Buggle and one of the UK’s most influential producers, in his own 1979 Number One hit. His SARM studios, East and West – one off Brick Lane that closed recently, the other in a former church in Notting Hill – were stuffed with said new technology.

Horn and his late wife Jill Sinclair bought SARM West from Island’s Chris Blackwell and it’s something of a house of the holy. Bob Marley, Nick Drake, Roxy, Eno, Sparks, The Clash, The Stones, Zeppelin, Genesis, Yes and Pet Shop Boys among others all recorded there. The building was also home to the ZTT label, which Horn set up with his wife and NME hack Paul Morley. While the label had other acts – among them Propaganda, Hoodlum Priest, Art Of Noise and 808 State – they were steamrollered by Frankie Goes To Hollywood, who were pretty awful on first sighting. The evidence was laid bare when an unsigned Frankie appeared on Channel 4’s music show ‘The Tube’ in February 1983 with a sort of jazz funk version of ‘Relax’. Called ‘Relax (In Heaven Everything Is Fine)’, it was remarkable only for the amount of leather, hand guns, whips and handcuffs on display at teatime on a Friday. They did catch the attention though.

By May, Horn had signed them to ZTT and work began on their debut single. The first version of ‘Relax’ was recorded live, a la ‘The Tube’, which Horn later described as “pretty awful”. By version two, Frankie were a different band. Literally. They were Ian Dury’s band The Blockheads whose version was also discarded for being too tame. By version three, Horn and keyboard player Andy Richards had hit the Nepalese dope and they stumbled on the now familiar pumping rhythm while mucking around with the Fairlight.

Costing £18,000, a heart-stopping half a fortune at the time, the Fairlight arrived just in time for use on Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Duck Rock’. Released in 1983, ‘Duck Rock’ served up ‘Buffalo Gals’, one of the very first records to feature singing, rapping and scratching on one tune. Horn offers up ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’ as the only other record at the time to feature scratching. McLaren, ever the magpie, tapped right into the mainline with ‘Duck Rock’, which oozed New York cool, enlisting the likes of the Ebonettes for ‘Double Dutch’ and shipping in The World’s Famous Supreme Team hip hop crew to provide scratching on ‘Buffalo Gals’. “I showed them the Fairlight,” Horn told Sound On Sound magazine. “I thought their heads would explode, but instead their eyes went blank and they just wanted decks.”

As the kit got progressively better, Horn became increasingly interested in sampling, which came to the fore with his Art Of Noise side-project and their 1984 ‘Close (To The Edit)’ single, containing the first ever sampled and sequenced bassline. But it was the sampling of quirky founds sounds and building entire songs from them that caught the attention. In late 1987, the house engineer at Sheffield’s FON Studios, one Robert Gordon who went on to co-found Warp Records, was slipping an Art Of Noise sample into Age Of Chance’s white label ‘Kiss’ mash-up, ‘Kisspower’.

FON had an early sampler, an Akai S900, in the studio and ‘Kisspower’, which features slices of everyone from Springsteen to The Supremes, gave it a thorough run-out. Age Of Chance subsequently ordered a trio of the £3,000 machines and began planning how they could be used live, the band’s bass dominator Geoff Taylor telling us recently that they were huge fans of Sweden’s The Young Gods who took a similar groundbreaking approach when it came to using samplers live. The Akai’s built-in hard drive could hold 63 seconds at a sorry 7.5kHz or you could swap samples in and out from floppy discs on the fly, which anyone who played live with one these machine will tell you, was stone-cold terrifying.

January 1979

Blondie

‘Heart Of Glass’

(A&M)

Despite popular belief, and putting the kibosh on nice piece of symmetry, the video for ‘Heart Of Glass’ wasn’t shot in New York’s legendary Studio 54 nightclub. Even so, you hardly need any encouragement to acknowledge the influence of Blondie.

Debbie Harry had been talking about Moroder a fair bit in the 70s, telling the NME in February 1978 that it was “the kind of stuff that I want to do”. By May, her band had covered ‘I Feel Love’ during a CBGB’s benefit for Johnny Blitz, the drummer with Cleveland punk outfit The Dead Boys, who was recuperating after an altercation which left him with multiple stab wounds. The Dead Boys also performed at the show… with John Belushi on drums.

If it was ‘Heart Of Glass’ that hooked us in, the sucker punch came a year later in the shape of ‘Rapture’. The repetitive beat, the disco overtones and the funny talking bit, which we didn’t know was called “rapping” yet. Crucially, the song introduced us to a whole new world of Fab Five Freddy and Grandmaster Flash, whose 1981 DJ journey ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’ returned Blondie’s favour by using a slice of ‘Rapture’. Freddy meanwhile was the spark behind the seminal hip hop movie ‘Wild Style’ and his 1982 ‘Change The Beat’ track is a well sampled hip hop cut, with magpies including Herbie Hancock who used it on ‘Rockit’.

September 1981

Depeche Mode

‘Just Can’t Get Enough’

(Mute)

The third single to be taken from their debut ‘Speak & Spell’ album, ‘Just Can’t Get Enough’, was to prove both the beginning and the end. It was the third and final single to be written by Vince Clarke before his departure to pure pop world. Yazoo with Alison Moyet and Erasure with Andy Bell followed and, if indeed he was proving his point, he proved it pretty well.

Seems Depeche Mode had another songwriter up their sleeve and with Martin Gore on duty they went intergalactic. Their first six albums came in just as many years serving up a couple of dozen hits during the 80s alone. Popular then, prolific for sure, but it paled beside what happened next.

They went from the Essex proto boy band who put Daniel Miller’s Mute label in the shop window to black-clad demigods ready to make the US their own in the blink of an eye. A dark melancholy found its way into 1986’s ‘Black Celebration’ and they built on it with 1987’s ‘Music for the Masses’, an album that saw them own the States. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor heavily name checks the Mode as does Detroit techno legend Derrick May, which says a lot. The ‘101’ tour doco, which chronicles the final leg of their 1988 world tour and its 101st show at the Pasadena Rose Bowl in front of 60,000 delirious fans, shows just how off the scale the US went for the Mode. And ‘Violator’ was yet to come.

February 1980

Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark

‘Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark’

(Dindisc)

11 September 1975. The Liverpool Empire. Seat Q36. It was the sixth show in Kraftwerk’s UK tour supporting the imminent release of ‘Radio-Activity’. It was also when the world shifted on its axis for 16-year-old George Andrew McCluskey. “It was the height of long hair, flared denim and lead guitar solos,” he said of the first night of the rest of his life, “and they came out looking like four bank clerks with electronic knitting needles and tea trays. It was like an alien spaceship had landed.”

In the subsequent years, you will have heard McCluskey waxing lyrical about Kraftwerk. His assertion that they are as important as The Beatles is often met with hoots, but he’s not wrong.

“‘Radio-Activity’ was the bible,” he told The Quietus in 2013. “We were listening to ‘Radio-Activity’ going, ‘Well, they got Geiger counters, and chopped up voices and tuning radios and we can do that!’. Completely inspirational because we had fuck all – I had a left handed bass guitar and Paul [Humphreys] had bits of circuit boards taken out of radios that he had welded together to make weird noises with, so ‘Radio-Activity’ was the be all and end all, and we listened to it incessantly.”

Roxy Music, ‘Heroes’, Neu!, La Düsseldorf and Kraftwerk was quite the path of musical discovery for the 1970s teen. What Orchestral Manoeuvres did with that knowledge saw them serving up one of the very first electropop albums in the shape of their eponymous debut album. Which is remarkable in itself. More remarkable is that the precursor, their debut 1979 debut single ‘Electricity’, was released on Factory Records. Which, looking back, is akin to Ghostbusters crossing the streams. The worlds of Kraftwerk and Factory colliding thanks to OMD.

Factory’s in-house design team, Peter Saville and Ben Kelly, further added to the fuddle by turning in sleeve artwork for Dindisc, a Virgin subsidiary set up by Carol Wilson. Their work included the sleeve for the OMD’s debut album, who came to Dindisc via… “Tony Wilson gave me the band because he felt they needed a label with a more commercial approach,” says Carol, explaining how her first signing arrived on a plate. Marvel as writer’s head explodes

October 1981

The Human League

‘Dare’

(Virgin)

The story of ‘Dare’ we know. What’s often overlooked is the impact those Human League recording sessions had on popular music as a whole and the effect it had on the entire city of Sheffield. The epicentre was the late Martin Rushent’s Genetic Studios, halfway up a hill over looking the Thames Valley in leafy Berkshire.

In 1978, Rushent, who’d earned his chops producing The Stranglers and Buzzcocks, moved from Henley to Wood Cottage on Aldworth Road in the picture postcard village of Streatley. In the back garden of the new family home was a dilapidated bungalow in which he set up shop. The plan was for a custom-built studio on the plot, but for now, the bungalow took the strain.

Rushent’s pal Rusty Egan was the first arrival in 1979. Egan, along with London scenester Steve Strange, ran a Bowie/Roxy night in Soho. Wanting some new sounds to play, Egan roped in his Rich Kids bandmate Midge Ure and they headed to Berkshire at the invitation of Rushent. Every now and again, he’d stick his head round the door to see what Visage were up to and ended up lending a hand… not to mention getting to grips with some new fangled kit that wasn’t familiar weaponry to a producer of punk bands.

How The Human League came his way depends on who you talk to. Rushent had spotted an advert for a Roland MC-4 MicroComposer, thought it looked pretty good and bought one along with a Roland Jupiter to mess about with. The bungalow had a bedroom out the back, occupied from February 1981 by former Buzzcocks frontman Pete Shelley who Rushent was helping with some demos. Virgin MD Simon Draper heard the demos and, while he didn’t sign Shelley, he was looking for a producer to add punch to his new signing, The Human League. The League arrived in Streatly in March 1981 with a multi-track tape of ‘The Sound Of The Crowd’. Draper told the band Rushent was going to mix it. He chucked it in the bin and started again.

Genetic became home to ‘Dare’ by day and Pete Shelley’s ‘Homosapien’ at night. Recorded in the same studio, at the same time, using the same production team and the same kit, ‘Homosapien’ and ‘Dare’ are very close relatives, with Rushent and his engineer Dave Allen working out how the heck their mountain of new machines (including a Synclaivier, a Fairlight and one of the first Linn drum machines in the UK) worked on the fly as they simultaneously put together both records.

The thundering success of ‘Dare’, released in October 1981, and the chart avalanche of ‘Don’t You Want Me’ in December was a coming of age for Sheffield. Following The Human League’s success, major label money wasn’t in short supply for Steel City acts. Chakk got picked up by MCA Records and sank their sizable advance into their own recording facility, FON Studios, which opened in 1985. Their record shop, FON Records on Division Street, morphed into Warp Records – a shop, a genre-defining label and a film production company.

More remarkable perhaps was the council-run Red Tape Studios, a bold initiative that housed recording and rehearsal spaces as well as offering training courses for the unemployed, which opened in 1986. Heaven 17, Clock DVA, ABC, Cabaret Voltaire, Ashley & Jackson, Forgemasters, Krush, LFO, Moloko… ‘Dare’ was just the beginning and its success gave the city the confidence to stand alongside the northern musical powerhouses of Liverpool and Manchester.

June 1982

Vangelis

‘Blade Runner’

(EMI)

First it was Aphrodite’s Child with Demis Roussos, then he was considered (unsuccessfully) as Rick Wakeman’s replacement in Yes, meeting singer Jon Anderson in the process and landing a few hits as Jon & Vangelis in the early 1980s. But for Evangelos Odysseas Papathanassiou all that mucking about with prog was but a distraction.

Throughout the 1970s he’d scored a number of commercials and documentaries and had met director, Hugh Hudson, who invited him to work on his 1981 film ‘Chariots Of Fire’. His uplifting soundtrack, which is always rolled out whenever there’s footage of anyone running, bagged Vangelis an Oscar. More curious though is the story of his 1982 ‘Blade Runner’ soundtrack. Set in a dank, neon-lit future Los Angeles (2019!), Vangelis turned in a work that is as much a part of the film as the story itself and built on the idea evident with ‘Chariots Of Fire’ that machines weren’t capable of creating an emotional response in the same way orchestras could. But the groundbreaking soundtrack would remain unreleased until 1994, which only added to its status.

At the time, fans had to settle for an “orchestral adaptation of music composed for the motion picture by Vangelis” by the New American Orchestra. The official line simply claims a dispute prevented the OST’s release. According to sleevenotes from one of the many bootlegs that appeared over the years, Ridley Scott had a number of composers lined up in case Vangelis didn’t work out, which couldn’t have engendered a healthy working environment. Indeed, Scott went on to include additional music not composed by Vangelis, which sparked a contractual dispute resulting in the composer’s subsequent refusal to allow the release of his soundtrack. All rumour and speculation, but what it did do was imbue the work with mythical status. Oh, and in a neat piece of symmetry, Demis Roussos appears on the soundtrack: it’s his dulcet tones you hear on ‘Tales Of The Future’.

October 1983

Various Artists

‘Street Sounds Electro 1’

(Street Sounds)

Greg Wilson, legendary soul DJ, Haçienda resident, Revox wizard and the first UK DJ to mix live on the telly, is always a man worth listening to. “It’s a major flaw on the part of UK dance historians that the impact and influence of these albums has been largely underplayed and, more often than not, completely omitted,” he says of Morgan Khan’s London-based ‘Street Sounds Electro’ compilations, which pumped out big US imports and in the process introduced the idea of the mixtape to the UK.

Mixed by Herbie Laidley’s Mastermind collective, featuring Max LX and Dave VJ who went on to join Kiss FM, the influence of the ‘Street Sounds Electro’ series, all 22 volumes, is beyond doubt. These albums sold by the barrow-load, mainly to breakdancing crews on cassette. The blueprint for the whole of British dance music culture is pretty much here. Just listen to ‘Electro 1’. Opening track – The Packman’s ‘I’m The Packman’ – fades up (yes, fades up) and it’s basically ‘Confusion’. New Order were, as we know, influenced by electro, on this collection of early imports that influence is laid bare. Newcleus’ ‘Jam On Revenge’ is a total banger and yet sample-wise it’s relatively untouched. Nightmares On Wax’s ‘(Man) Tha Journey’ from ‘Smokers Delight’ is pretty much a cover though. It’s why you have to love NOW so much. They know what we know.

Electro was by no means an underground sensation. In the UK it took hold of the charts with the likes of Rock Steady Crew landing sensationally large hits in 1984, with records packed to the gills with 808s, 909s and 303s, scratching and videos stuffed with breaking dancing and body popping.

March 1983

New Order

‘Blue Monday’

(Factory)

Yeah. It’s difficult, impossible even, to trace an electronic music timeline without touching on ‘Blue Monday’. Up to that point, New Order were between two stools, caught in the Joy Division headlights yet trying desperately to move forwards. Their first single, ‘Ceremony’, was a Joy Division song and sounded like it. By May 1982, they were beginning to loosen the shackles with the rippling sequencer riff of ‘Temptation’, but nothing could prepare the world for ‘Blue Monday’, the non-album single released upfront of their second album, ‘Power, Corruption & Lies’.

If you were a record buying oik at the time and you rushed out to snap up the album on the back of being blown to pieces by ‘Blue Monday’, you will know the disappointment. The music press queued up to proclaim that with ‘Power, Corruption & Lies’ New Order had finally stepped out of the Joy Division shadows. They hadn’t. The consolation prize was ‘Blue Monday’ prototype ‘5 8 6’, which at the time wasn’t really enough. Sounds ridiculous some three decades on as it’s clearly a great New Order album, but alongside the game changing ‘Blue Monday’ it sounded less than impressive. There was a familiar calling card on ‘Blue Monday’ too – the haunting Vako Orchestron choral wash as heard on ‘Uranium’ from Kraftwerk’s ‘Radio-Activity’ album was worn bold as brass. Where were this lot going with references like that? ‘Technique’. We had ‘Technique’ to look forward to.

October 1984

This Mortal Coil

‘It’ll End In Tears’

(4AD)

While I had no idea who Tim Buckley was, his ‘Song To The Siren’ cover by 4AD house band This Mortal Coil was a revelation. I loved the Cocteau Twins, whose sound – a sonic pushing forwards – was like little else. Yet here, on a “proper” song, Liz Frazer was singing real words, in the right order and somehow that marked ‘It’ll End In Tears’ out as the beginning of a love affair that would end up by being blown away by a guitar band.

4AD had emerged some years earlier the brainchild of Ivo Watts-Russell and Peter Kent, who worked for Beggars Banquet and set up the label as an incubator imprint for the mothership. Didn’t work out that way and the only band to tread that path were Bauhaus before Watts-Russell and Kent bought the label off Beggars and set sail as an indie. Kent left in 1981 to set up Situation Two, releasing the likes of The Associates, Bauhaus side-project Tones On Tail, Gene Loves Jezebel as well as The Charlatans and Buffalo Tom.

Much like Factory, 4AD also had a strong visual identity thanks to graphic designer Vaughan Oliver and photographer Nigel Grierson. Fortunately, the musical output matched the bold 23 Envelope artwork. They released the debut The The single, ‘Controversial Subject’, while Rema-Rema, Modern English, Xmal Deutschland, Clan Of Xymox and The Wolfgang Press were early highlights. Things got really interesting when in 1985 Colourbox arrived with their debut album. They went on to join forces with AR Kane, who with DJs CJ Mackintosh and Dave Dorrell, formed MARRS and landed 4AD with Number One hit ‘Pump Up The Volume’ in August 1987.

4AD were never afraid to mix things up. From goth to electro, whatever angle you came in at, you went away with something else. A proliferation of US guitar bands dominated the label in the late 80s, bringing on board the likes of Throwing Muses, The Breeders, Belly and, hands down the greatest guitar band of the last 30 years, Pixies, who didn’t pen a duff song across their quartet of 4AD albums. It’s hard to think of a label as diverse who wowed so utterly.

The Ravers

May 1987

Frankie Knuckles

‘Baby Wants To Ride’ b/w ‘Your Love’

(Trax)

It wasn’t the first. The first is a matter of debate, but we’re going for Jesse Saunders’ ‘On And On’ from 1984, a primitive blend of disco loops and spiky 808 drums typical of the early Chicago house sound. It might not have been the best either. Let’s face it, if we’re trying to pick one record to represent 1980s Chicago house music, we’re spoilt for choice. So we could just as easily be talking about Marshall Jefferson’s ‘Move Your Body’, which somehow managed to appear simultaneously on both the main Windy City record labels, Trax and DJ International, or Farley “Jackmaster” Funk’s ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’, featuring the incredible vocals of Darryl Pandy. Or maybe JM Silk or Fingers Inc or Adonis. But we’re talking about Frankie Knuckles because Frankie Knuckles, who died in 2014 at the age of 59, wasn’t called the Godfather of House for nothing.

Knuckles’ status largely comes from his role as the DJ at The Warehouse, the Chicago club from which house music takes its name. Knuckles started at The Warehouse in 1977, playing disco and soul and a growing number of European synth records to what was initially a black, gay crowd. Ironically, he’d left The Warehouse to start his own club, The Power Plant, before the earliest jack records appeared. Not long after Jesse Saunders’ ‘On And On’ came out, Knuckles was given a tape of ‘Your Love’, a track based around a cascading synth sequence by a young man named Jamie Principle, whose vocals sounded like Smokey Robinson channelling Marc Almond. Knuckles played ‘Your Love’ at The Power Plant for a year before taking Principle into the studio to produce a more polished version of the track along with a second cut, the eerie and provocative ‘Baby Wants To Ride’.

The cuts appeared back-to-back as a Trax 12-inch in 1987. The record was attributed to Frankie Knuckles and Frankie Knuckles alone. Principle was given a writing credit, but that was it. Which is perhaps why, when the singer later re-recorded ‘Baby Wants To Ride’ with Steve “Silk” Hurley for FFRR in the UK, there was no mention of Knuckles. Touche. It wasn’t a patch on Knuckles’ original, mind.

October 1988

Front 242

‘Headhunter’

(Wax Trax!)

Front 242 were veterans by the time of the ‘Headhunter’ single – from their fourth album, ‘Front By Front’ – but it was the song they were born to make: a rough bastard of a tune that spat its influences onto the dancefloor, opening ears for the Year Zero of rave that was just around the corner. But for the time being EBM had arrived…

A slowly percolating offshoot of industrial music, EBM was spearheaded by Belgian mainstays such as Front 242 and The Neon Judgement, and roped in the likes of Chris & Cosey.

‘Headhunter’ was the genre’s defining statement. It had the lyrical bite of Foetus, the wit of Fad Gadget. It had the propulsive dance mechanics of Cabaret Voltaire’s ‘Sensoria’, the sleaze of Big Black’s ‘Songs About Fucking’ and the stentorian death march of DAF – all of it filtered through the knowledge that while Front 242 were the godfathers of the EBM scene they had serious competition in the shape of Canada’s Skinny Puppy and the UK’s own Nitzer Ebb.

In one of the great “why on earth was that a B-side?” decisions, Front 242 decided to back ‘Headhunter’ with a track that was arguably just as strong: ‘Welcome To Paradise’. Unsurprisingly both sides were caned everywhere, with DJs finding the tracks dovetailed neatly with the emerging genre of new beat.

Shortly after, new beat producers inspired by the UK rave scene placed Belgium at the vanguard of techno. Ghent-based label R&S moved seamlessly from Belgian new beat to house and techno and in time would give us Second Phase’s ‘Mentasm’, birthplace of the legendary hoover sound, not to mention Aphex Twin’s ‘Digeridoo’ and ‘Selected Ambient Works 85-92’. But that, of course, is another story…

September 1987

Phuture

‘Acid Tracks’

(Trax)

After Frankie Knuckles had left The Warehouse, the owner opened up a new Chicago club called the Muzic Box and recruited Ron Hardy as the resident DJ. Hardy was a completely different character to Knuckles and, thanks to his often feverish approach to EQing and pitch control, the records he played were generally brasher and faster. He had a fondness for Frankie Goes To Hollywood, but he was quick to play all the emerging local house artists too. The night he got hold of a tape of Phuture’s first offering, a 12-minute mash-up of hypnotic pulses and oddball squelches (the latter courtesy of a Roland 303 bass synth), he played it four times. It didn’t have a title, so the Muzic Box crowd dubbed it ‘Ron Hardy’s Acid Track’. By the time it came out on Trax Records, with Marshall Jefferson on production duties, it was called ‘Acid Tracks’.

‘Acid Tracks’ is a monster of a record. But if it was big in Chicago, it was super-sized-massive-with-bloody-great-bells-on in London, where it was one the first cogs of the acid house revolution. In many ways, it was strange that London took to acid so readily, with Danny and Jenny Rampling’s Shoom club and Paul Oakenfold’s Spectrum exploding in popularity as the summer of 1988 rolled on and dozens of other acid nights started up to cater for the growing hordes of kids in bandanas and smiley T-shirts. Up until then, only a handful of London DJs had been playing house music, most notably Noel and Maurice Watson, Colin Faver and Mark Moore. By contrast, the north and the Midlands had been jacking to house for a good couple of years thanks to the likes of Mike Pickering in Manchester and Graeme Park in Nottingham.

A night of acid house didn’t mean hours of squelchy noises though. To begin with, there weren’t actually too many records like ‘Acid Tracks’ around and one of the most amazing things about the early acid clubs was the variety of music you’d hear. There were lots of US house tracks, of course, with some of the most thrilling sounds of 1988 coming from New York producer Todd Terry, as well as cuts by early UK adopters like 808 State, A Guy Called Gerald and Baby Ford. But there were also records such as Finitribe’s ‘De Testimony’, Gipsy Kings’ ‘Bamboléo’, The Woodentops’ ‘Why Why Why’, Nitzer Ebb’s ‘Join In The Chant’ and even The Rolling Stones’ ‘Satisfaction’. And as for the night that Paul Oakenfold dropped a bit of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture into the mix at Spectrum…

“How you gonna get ridda the acid, man?” said Marshall Jefferson in an interview with Melody Maker during a trip to London that summer. “Everybody’s on it, everywhere you go the acid is pumping. You can’t match the energy level. Until a DJ gets bold enough to pioneer a new music, you’re gonna hear it wherever you go.”

June 1988

Various Artists

‘Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit’

(10)

Much has been written about the role of the so-called Belleville Three – Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, three schoolmates from the Detroit satellite town of Belleville – in the birth of techno. They grew up messing around with the electronic gear in the back room of Grinnell’s music store. They listened to The Electrifying Mojo’s local radio show, where they heard Kraftwerk and Numan alongside Parliament and Prince. They danced to Ken Collier’s post-disco DJ sets wherever he was playing around Detroit.

It was Atkins who started it all off, warp factoring the electro blueprint into another dimension on ‘Techno City’, issued in 1984 under the name Cybotron, and ‘No UFOs’, his 1985 debut as Model 500. It was May who upped the ante with Rhythim Is Rhythim’s ‘Nude Photo’, complete with its sample of Alison Moyet laughing lifted from Yazoo’s ‘Situation’, and the colossal ‘Strings Of Life’. And it was Saunderson who put it into pop charts via Inner City’s ‘Big Fun’ and ‘Good Life’.

The Belleville boys were by no means alone in this story, though, as the ‘Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit’ double album proves. Kind of. For a lot of people outside of Detroit, the first they knew of the music coming out of the Motor City in the second half of the 80s was this UK compilation. It was released by 10 Records, a Virgin offshoot based in a mews off London’s Portobello Road, where the cobbles and flower boxes were about as far removed from Detroit’s industrial landscape as you could get, and put together by Derrick May and 10 A&R man Neil Rushton, who later started the Network imprint. While it’s true that Atkins, May and Saunderson are all over these tracks, co-writing, co-mixing, co-producing much of what’s here, it also includes early material from a number of other key techno pioneers, including Eddie “Flashin’” Fowlkes, Blake Baxter and Anthony Shakir.

There isn’t a duff cut on it, but perhaps the single most important thing about this record is the title. It was originally going to be called ‘The House Sound Of Detroit’, but the artists insisted changing it to include “techno”, the word they were using to describe their music, rightly setting the Motor City apart from what was going on in Chicago and establishing its credentials as a crucible of innovative electronic music. Step forward Carl Craig, Jeff Mills, Richie Hawtin, Mike Banks, Robert Hood, Kenny Larkin, Stacey Pullen and Drexciya, to name but a few.

November 1989

Happy Mondays

‘Hallelujah’

(Factory)

Happy Monday’s quirky funk rock debut album, ‘Squirrel and G-Man Twenty Four Hour Party People Plastic Face Carnt Smile (White Out)’, released in April 1987, was produced by John Cale, Velvet Underground John Cale. Which sounds increasingly bonkers the more you think about it. The now-famous title track, ‘24 Hour Party People’ was only included after a track called ‘Desmond’ made way due to a copyright dust-up with The Beatles’ ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’. Not for the last time would the Mondays borrow from The Beatles. ‘Lazyitis’, the closing track on their ‘Bummed’ album, was pretty much ‘Ticket To Ride’. Other influences, while less obvious, were more telling. For example, the louche beats and infectious groove of ‘Halleluhwah’, from Can’s 1971 album ‘Tago Mago’, after which the Monday’s own track was named, is a dead giveaway.

While the late Martin Hannett should take credit for reinventing the Monday’s sound on their sophomore album, 1988’s ‘Bummed’, it was when they got the remixers in that things shifted up a gear. It was ‘WFL’ – Vince Clarke’s reworking of ‘Wrote For Luck’ – that first pricked up the ears. There was also ‘WFL (Think About The Future Mix)’, which marked the arrival of Paul Oakenfold who created a number of defining mixes for Ryder and co, not to mention co-produce the ‘Pills ’n’ Thrills And Bellyaches’ album along with Steve Osborne.

The choice of remixer on ‘Hallelujah’ was inspired with Oakey calling on Andrew “Andy” Weatherall and Terry Farley to help out and so introducing the pair to a whole new crowd. Literally. You can’t understate the importance of the Haçienda in all this. That place opened the ears and changed the lives of so many people. Oh, and if there was a clubber who didn’t know Shaun Ryder’s middle name after hearing ‘Hallelujah’, well, they weren’t paying attention. Or they were off their face on a new fangled drug that seemed to have swamped the Hac. Now there’s a good story…

February 1992

Aphex Twin

‘Selected Ambient Works 85-92’

(R&S)

When, in 2014, it was announced that Richard D James was to release his first album of new Aphex Twin material for 13 years, there weren’t many who hoped for another ‘Drukqs’. Thankfully, ‘Syro’ turned out to have less in common with the scaffolding accidents of ‘Drukqs’ and was more along the lines of the record that made his name: ‘Selected Ambient Works 85-92’.

His debut long-player wasn’t particularly “ambient”. Then again, nor was The Orb’s ‘U.F.Orb’, released the same year. But both came at a time when, having been informed by house and techno, energised by hardcore’s breakbeats and given a cerebral edge by the progressive nature of Boy’s Own and Guerrilla, the UK dance scene was at its most exciting. Of the two, ‘SAW’ was the more startling record, eschewing the dubwise leanings of the prog and ambient house scenes for a more insular fragile beauty. Like Hemingway’s literary maxim of “it reads easy, it worked hard” set to music, simple melodies masked complex arrangements and structural intricacies.

As a result it reached places dance music hadn’t yet penetrated: the offices of national music papers, sixth form common rooms, bedrooms… UK techno already had Orbital and James’ own ‘Digeridoo’ to its name, but these spoke to a constituency centered on the communal rave experience. The analogue synths and otherworldly beats of ‘SAW’ made sense to those without cars and mates and contacts – the sort who spent their free time slaving over a hot VHS recorder, vibing to the horror film soundtracks of John Carpenter and Tangerine Dream. Less than a year on from ‘Screamadelica’, the portal was again open for huge swathes of non-dance listeners to come inside and feel the beats.

Like his music, James’ appeal was at once rarefied and universal. Like his music, he made it seem so effortless. And he did it all from his bedroom. While his peers projected a “creature-of-the-studio” image, Cornwall-based James came on like the geeky kid in ‘Dressed To Kill’, his living space crammed with gizmos, working odd hours, buzzing off caffeine and creativity. Though a dyed-in-the-wool raver, he appealed to the nerd in us all.

Which brings us to IDM. While the early Aphex EPs appeared on Belgian rave imprint R&S, it turned out that Sheffield’s Warp was the better fit. In the slipstream of ‘SAW’, Warp collected the likes of B12, The Black Dog, Autechre, Speedy J and James himself for the first ‘Artificial Intelligence’ compilation in July that year. Thus was born “intelligent dance music”. A lamentable label – as if B12 were really more intelligent than, say, Jeff Mills – but at the very least it freed a generation of like-minded bedroom tinkerers from the constraints of the dancefloor. Four Tet, The Streets, Burial, the glitchy minimalists of Cologne, Raster-Noton, Pole, Mille Plateaux… all those and more are indebted to the bedroom boffin template minted by Richard D James.

All that and we haven’t even mentioned the pranksterism, the tank, DJing with sandpaper, ‘Windowlicker’, ‘Caustic Window’, his legendary remixes, his revelatory DJ sets, the fact that he was barely out of his teens… By then it was only the likes of Kraftwerk and Giorgio Moroder who could lay claim to opening more doors. Come to daddy, indeed.

January 1994

Underworld

‘Dubnobasswithmyheadman’

(Junior Boys Own)

Long story short. 1988’s ‘Jack The Tab – Acid Tablets Volume One’ was a compilation of a fictitious genre where the aliases – Vernon Castle, Thee Loaded Angels, Alligator Shear – were collaborations between Genesis P-Orridge of Psychic TV, Richard Norris from the psychedelic label Bam Caruso, and Gen’s pal Dave Ball of Soft Cell fame. Norris and Ball went on to further bother the charts as The Grid.