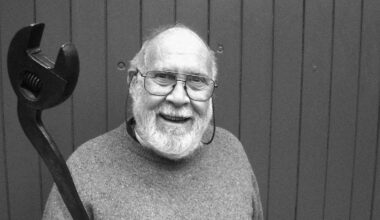

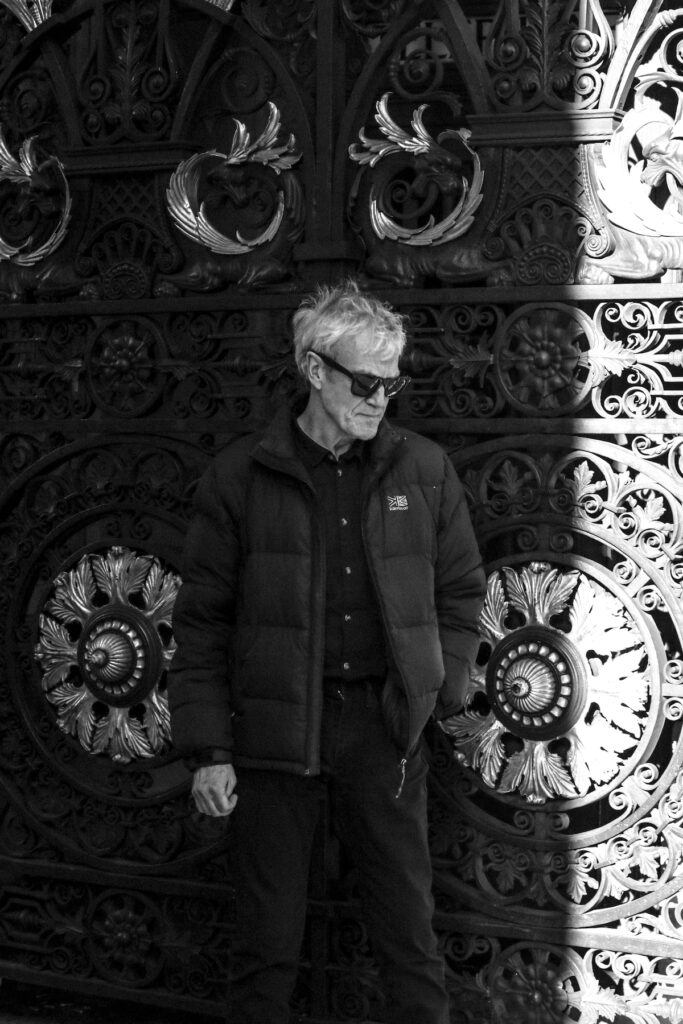

‘Howl’, the album from John Foxx And The Maths, seems spookily prophetic given these strange and unsettling times. We talk to Foxx and his Mathematicians – Benge, Hannah Peel and former Ultravox axeman Robin Simon – about heavy electronics, contorted guitars, violent violins, and howling into the void

“Every time I put the news on, it’s like Ballard’s been scripting it,” says John Foxx as we hunker down in a Piccadilly coffee shop for a chat about his new album, ‘Howl’. “You think it can’t get any worse, and then it does.”

We allow ourselves a wry chuckle. JG Ballard, chronicler of the human animal’s willingness to turn on itself, could indeed have plotted our current narrative – a malignant narcissist in the White House, a horrific and endless proxy war in Syria, Australia on fire. Closer to home, a eugenicist sociopath is pulling the strings in Downing Street and Brexit-flavoured racism is on the rampage, while freak weather events drown small English towns. Surely this is as bad as it gets?

Well, within two weeks of this interview, a global pandemic is announced by the World Health Organisation. Jesus H Christ. You think it can’t get any worse and then it does. As Foxx seems to be saying on the psychedelic ‘Everything Is Happening At The Same Time’, one of the highlights of ‘Howl’, with its ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ swirls and beat, it’s like living in a hallucination of constant, unbearable news, and being powerless to do anything about any of it.

If that’s the overarching theme of the forthcoming John Foxx And The Maths album, Foxx and his co-conspirators – electronic studio whizz Benge, composer/sound artist Hannah Peel, and former Ultravox guitarist Robin Simon – have certainly summoned up a suitably ragged and desperate sound world to express it. Everything here comes at you with a feral ferocity, with electronics and guitars and all kinds of wild textures bursting in multicoloured plumes of distortion. It’s a record about a world on fire, about death, sex, depravity and pain. It’s Foxx’s ‘Atrocity Exhibition’, a loosely bound collection of surreal and disturbing images that come thick and fast, like the sinister character described in ‘Last Time I Saw You’, over a buzzsaw drone of synths and guitar.

Sonically, ‘Howl’ is like Ultravox never split up, but ramped up the post-punk noise, with Foxx surgically implanting the pitiless electronics of ‘Metamatic’ into the frenzy.

It’s not all Sturm und Drang. There are some tender moments (like the heartbreaking closing track ‘Strange Beauty’) and some humour. But the takeaway from its eight tracks is that this is one heavy album of rage from the normally disciplined and orderly John Foxx.

So was this the plan? Did he intend to create a raging, raw album for this age of horrors?

“Exactly,” says Foxx. “When punk happened, everybody was screaming all the time, but I thought it was a bit stupid. You can only stay angry for so long, and those bands petered out quickly, partly because of that. You can’t sustain it without acting it all the time. Later on, electronic music offered this very psychotic detachment thing and that’s where the anger went. It’s my contention that it went into this very controlled anger – still anger – that manifested itself in a different way. It was great, because it meant you could have a different angle on it and not sound like everybody else. But now that time is over, so I thought, ‘Right…’.”

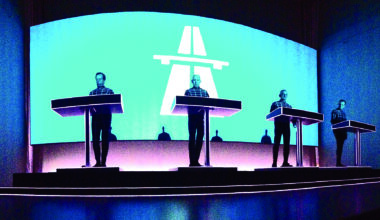

‘Howl’ represents a new statement, one which John Foxx hopes will dodge the shadow of Kraftwerk and reconnect with his Ultravox of the 1970s, which in many ways was an unfinished project.

“I got sick of Kraftwerk and all that,” he says. “I thought, ‘I have to get rid of Kraftwerk’s ghost somehow’. I was listening to a few things that I’d done with Ultravox, like ‘The Man Who Dies Every Day’ [from the band’s second album, ‘Ha!-Ha!-Ha!’], and that struck a chord better than anything else, so I thought I’d like to get a hold of some of that again.”

Recruiting Robin Simon to The Maths was the moment everything fell into place. Simon had joined Ultravox at the end of 1977 for what was to be their final tumultuous year or so of pre-Midge existence and he’d brought an armoury of guitar techniques to the band. For a brief period after punk and before the synth revolution of the early 1980s, the likes of Magazine’s John McGeoch, Television’s Tom Verlaine, and Public Image Ltd’s Keith Levene turned the guitar into an extraordinary polyphonic noise generator, building towers of beautiful melodies which they demolished as soon as they were thrown up, deconstructing and reconstructing them in a constant maelstrom of notes, effects, yelps and percussive anxiety. Colin Newman of Wire, the late Andy McGill of Gang Of Four, and Robin Simon were all at it. The intervening 40 years seem to have only intensified Simon’s approach.

“Robin came into the studio to work on a song I’d written called ‘Something Is Coming Down The Avenues’,” says Foxx. “He just [laughs] did that with his guitar and I thought, ‘Bloody hell!’. We were all stunned. I was thinking, ‘That’s buggered that song completely, but it’s much better than it was’. I couldn’t sing the original vocal to it anymore, so I said to Benge to keep that take, the one take he did, and I took it home to see what I could do with it.”

The song became ‘Howl’, which gave the album its title and set the tone for the overall sense of pent-up desperation and intense release. It starts with Simon’s guitar, which has a similar explosive impact to Robert Fripp’s contribution to Bowie’s ‘It’s No Game (No 1)’ on ‘Scary Monsters’. The song is filled with allusions to the Golden Mile, glitter and letting the beast out. What’s it about?

“Trying to explain lyrics sometimes can sound a bit mad, but I was briefly at art school in Blackpool and everyone used to go down the Golden Mile,” says Foxx. “It was always magic when I was a kid.”

The Golden Mile – a wide boulevard filled with the lights and noise of all the seaside entertainments you could wish for – is Blackpool’s pride and glory. Arcades, casinos, bars and the Illuminations, it’s a windswept and often rainy English stab at the thrills and trashiness of Las Vegas, with added brawling and fish ’n’ chips.

“Everyone was always absolutely drunk and there were loads of fights, particularly in Glasgow holiday week,” continues Foxx with a smile. “It had this mix of magic and mayhem which everybody loved. I always wanted to write a song about it.”

He was reminded of the Golden Mile’s seething humanity when he was in Manchester for last summer’s Subliminal Impulse festival.

“Some people get drunk and just howl on the street. They just shout. I saw two people doing it in Manchester last year. I hadn’t seen it for a bit. It seems to be a particularly northern thing. I thought, ‘Oh yeah, I remember, the shouters’. There’s always a couple of shouters – drunk, letting rip. Sometimes it’s people with mental health problems, but there are a lot of drugs in Manchester too, those new synthetic things that drive you barmy. It jolted me and made me think of that. I’d also just been reading ‘Howl’, the Allen Ginsberg poem.”

Foxx identifies this howl, a kind of pained expression of the universal id, existing within the performance art of people like Leigh Bowery, as well as street drunks and beat poets. Bowery, the Australian-born, London-based performance artist, died in 1994 at the age of 33. He had delighted and scandalised the UK in equal parts, thanks to his always controversial public appearances and his club night Taboo. Taboo was one of the first London club nights to enthusiastically adopt the drug ecstasy, which helped fuel the sexual debauchery for which it was famous.

“Bowery’s life was that howl,” says Foxx. “It’s a sort of, ‘I’m alive! You can’t ignore me! Here I am!’. He was completely surreal. I used to see him at The Fridge in Brixton in the early days of dance music, in 1987 and 1988. I remember thinking, ‘What’s that?!’. You’d see this thing like a spotted polony coming through the door, only it was about seven foot tall. He was fantastic. Then I saw him with Mark E Smith of The Fall, when he did ‘I Am Curious, Orange’ with Michael Clark. We had a chat when he was in that. I always wanted to get him into something, because he was such a landmark character. He’ll never get forgotten and he’s connected to so many people, from Lucien Freud to Boy George. He reminded me of New York in the late 1970s.”

Which leads us to the track ‘New York Times’, a celebration, or a memorial perhaps, of the New York City of the 1970s. NYC played a pivotal role in Foxx’s life after Ultravox were dropped by Island Records on New Year’s Eve in 1978. The third Ultravox album, ‘Systems Of Romance’, had failed to sell in quantities sufficient to keep the label happy, so the band struck out on a self-financed tour of America in early 1979. Foxx announced his departure in March of that year and Robin Simon went soon after, paving the way for the new iteration of Ultravox.

As his erstwhile bandmates were replacing him with Midge Ure, Foxx went back to America later in 1979 and spent some months in New York, shopping for the gear he would use to record ‘Metamatic’, his solo debut. Like so many other British musicians, he bought a lot of his equipment from Manny’s Music, near 6th Avenue. This was the same place that Hendrix shopped in the 1960s (he bought a 1969 Hammond Innovex Condor GSM Guitar Synthesizer, trivia fans).

Foxx’s trip was clearly a formative experience for him and the city’s reputation as a magnet for transgressives of all stripes is represented on ‘Howl’ in ‘New York Times’, a kind of update of the story of Sister Ray from the Velvet Underground song.

“The Bronx was on fire,” says Foxx. “People used to set fire to the buildings there. You’d come in on the train and there’d be smoke coming out of these warehouses in the Bronx. They had guards with sub-machine guns on the trains. It was a rough period.”

Things burning is a regular trope in Foxx’s output. ‘Burning Car’, for example.

“Yes, well, all that comes to mind. It does go through my stuff. It’s about urban disturbance. It’s a constant thing.”

From the Golden Mile to late 1970s New York City, Foxx is attracted to the rage and weirdness bubbling under the surface of society.

“Every freak in America headed to New York and it was complete mayhem,” he remembers fondly. “It was brilliant. Very dangerous but interesting. ‘New York Times’ is very much about the 70s and the feeling you got from Max’s Kansas City and places like that. I’ve been trying to nail that down ever since I first heard the Velvets in 1960-something. I’ve always liked ‘Sister Ray’. It’s a real fierce song. I liked New Order’s version of it too. They did a nice live version of it.

“So it’s like a recollection of things that I’ve seen and people that I knew. It’s gone now, it’s finished, but there’s still a legacy from the music that came out of that time. Even before the Velvets, when Dylan was doing ‘Blonde On Blonde’, that was essentially the beginning of it. It’s where Lou Reed took off, really. And Bowie and Warhol. There was a moment when it was all very exciting. It was great seeing William Burroughs down the Mudd Club. It felt like nowhere else in the world. No other city in the world was like that then.”

It wasn’t just music, it was the art scene too, and the two were symbiotic.

“I was talking to Vincent Gallo,” says Foxx. “He was working for Andy Warhol, doing squeegee things, so he’s got lots of Warhol stashed. He was homeless and he was sofa-surfing, but he spent all his money buying artwork, paintings by people who would become famous, and he would leave these paintings behind the sofa in his friends’ apartments. Some of them vanished, but the ones that didn’t are now part of this fantastic collection of 1970s New York art. He’s got the full spectrum, he’s got everything by everybody, and it’s an amazing collection. All that was happening at the same time and it was a fabulous period, so I had to write something about it.”

So the song is an attempt to capture…

“That feeling, how sleazy and lost, but how great it was.”

And those characters who populated it, like Sister Ray? Lou Reed knew those people: ‘Sailor’s hat, stolen clothes…’

“People were shoplifting all the time, bringing clothes they’d pinched from everywhere. It was quite funny.”

‘Howl’ deals with memory, then, the co-existence of the past and the present, and the inevitability of what the future has in store. It opens with the frenetic ‘My Ghost’. A punk guitar riff is bolstered by screaming synths and machine drums, like a ‘Metamatic’ cut put through a punk wringer. It’s about death, with the protagonist being pursued by his own ghost.

Foxx, astonishingly, is now in his 70s. Of course, 70 is the new 50 or something, and he appears as fit and healthy as ever. But we’re talking only a few days after the death of Andrew Weatherall, aged just 56.

“‘My Ghost’ is not morbid, but you’re aware of being chased by this thing,” says Foxx. “You feel like something’s in hot pursuit sometimes. And you’re only just avoiding it, because other people die, and people in rock ’n’ roll have been dying since I started. It’s a wonder there’s anybody left. People were dying in the 1970s and they’re dying now. There’s a long line of them, and you feel very close to it sometimes. When somebody says, ‘Have you heard…?’, you know?”

People like Andy Weatherall.

“Amazing isn’t it? You get a taste of mortality and you feel something breathing down your neck.”

Is making music an antidote?

“Definitely. It’s a way of staying alive. It keeps you alive. While you’re doing it, you’re immortal… for about 10 minutes!”

There’s a line in ‘Howl’ – “Future people know your name / Future people love your stories” – that’s about immortality, right?

“It’s about living longer than one generation, if you can manage it.”

When you’re involved in art that has an impact, you create a body of work that will outlive you. Do you think about that?

“Yeah. Everything you do lives longer than you do. That’s inevitable. Whether anybody’s interested or not is another matter, but it will be there after you’re dead.”

David Bowie showed the way. Perhaps it’s overstated that he stage-managed his death, but in terms of wrapping his legacy up…

“He did it very well,” nods Foxx. “He did everything very well and he did that particularly well. I was also thinking about when Sinatra died. They did this show, I think it was at the London Palladium, where it was a hologram of him performing. You get this reconstructed figure and you think perhaps this is the future, where people come back as holograms and they do a stage show that’s a 3D projection.”

Sex has always featured in John Foxx’s songwriting. On Ultravox’s 1977 debut album, ‘Ultravox!’, the band are lined up against a wall at night-time, posing beneath a neon sign of the band’s name, dressed in shiny PVC like they’re queuing for a Berlin fetish club. It’s a sleazy, New York Dolls kind of image, just right for the lyrics of ‘My Sex’, the track that closes the album – “My sex / Waits for me / Like a mongrel waits / Downwind on a tight rope leash”. On ‘Howl’, sex is placed centre stage with the song ‘Tarzan And Jane Regained’. It seems to be about rediscovering animal passions, an imaginary suburban sex drama.

“Reclaiming the territory,” smiles Foxx. “I always liked Tarzan and Jane when I was a kid. I had a conversation with a friend, a woman who’s a model, and she was saying we’ve lost it in England about the sexes. Everyone’s scared to compliment anyone now. She said she likes compliments, but she’s not getting them anymore. She says in France, it’s very formalised, and people know how to do it without causing offence. In fact, just the opposite, because people feel noticed and they feel they’ve got a value in various ways. I’m not protesting the fact that we don’t do that in the UK now, I can see the good reasons why – there are very good reasons why – but on the other hand, some of the fun’s gone out of life. That’s all I’m saying. There are times when you meet somebody and off you go. You’re Tarzan and Jane again.”

The song mentions the Italian shockumentary ‘Mondo Cane’, which caused a tabloid sensation when it was released in 1962. Foxx was 14 at the time.

“I remember it from when I was kid,” he laughs. “We used to hang around outside the cinema, but it was an X certificate. The cinema had a queue around the block because it had been in The People, which is the equivalent of The Sun, and they said, ‘Scandalous film! Do not see this movie! It’s against all English values!’. And of course, the next day there’s a queue around the block. As kids, we were busting to see it. We could see the stills outside, and all the write-ups said that it showed savage practices and unknown barbaric rituals, and I thought, ‘I can’t wait to see it!’. So I had to put a reference on the album. It’s part of that British hypocrisy, but it’s not really, because all the people queuing up knew what they were in for.”

So a celebration of pent-up sexual desires being unleashed? A call to slip the leash of contemporary puritanism?

“A lot of people take the moral high ground in order to look down on others, which is a great strategy,” laughs Foxx. “It always happens when there are new ideas. It happened with communism, with hippies, with religion in the Middle Ages. There are always people who want to look down on the rest of us.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

You might expect the author of all this sardonic commentary on the behaviour of his fellow citizens to cut a despondent, depressed figure, but Foxx is cheerful company. His eyes twinkle and humour is never far from the surface. In person, I tell him, he seems very jovial.

“I always am. It’s just that you can’t help but look around and have a howl, because that’s the times. And you do howl. And ‘Howl’ is an expression of all that. What it is, is, ‘AGGHH!’ Everything on the album is to do with that. But there is a bright side and I firmly believe that. I am an optimist at heart, oddly enough, so I think things will come through. It just takes time to refocus.”

Well, I’m glad to hear it.

As we leave the cafe and emerge into the street, the fearful sound of a baying crowd reverberates around the 19th century stone buildings of Piccadilly, down the narrow, diesel-choked canyons created by idling buses. It sounds like an urban disturbance is brewing. In fact, it’s 7,000 fans of the Greek football team Olympiakos, who are gathering in Piccadilly Circus ahead of that night’s match against Arsenal in the Europa League. None of us is particularly aware at this stage that a rampant, deadly virus is on its way.

This really could be a scene from a JG Ballard novel. This is Ballard’s London. It is also John Foxx’s London. He doesn’t live here now, but the city’s Palladian architecture and Brutalist concrete are imprinted in his music.

Foxx is in every underpass, every burned-out car, every fancy Southbank up-lit plaza surrounded by restaurants and bars, where the wealthy parade of an evening… until the virus empties the streets.

“Maybe the next album will be jolly,” says Foxx, but then he pauses to think for a moment. “I doubt it, to be honest.”