Hard as it is to fathom, the gold lamé and grand orchestral pop of Sheffield’s ABC developed out of post-punk experimentalist outfit Vice Versa. What were they putting in the water up there in South Yorkshire?

“There was fuck-all else to do,” says Vice Versa’s Mark White, co-founder of the experimental electronic outfit that would later morph into 1980s mega-popsters ABC. “I’m sure that’s why Sheffield was a major producer of pop music and pop culture.”

Should you need reminding, Sheffield’s momentous golden years, between 1978 and 1982, featured a hugely influential cast of innovators such as Cabaret Voltaire, The Human League, Heaven 17, Clock DVA, 2.3, Artery… the list goes on and on.

“It was all about filling time, in the old fashioned hobbyist sense,” continues White. “There might be one decent programme on TV at night worth tuning in for, so people started their own little bands.”

By the end of 1978, punk had pretty much fizzled out, and Sheffield in particular was undergoing something of a musical renaissance. For the disaffected new bands, desperate to escape the post-industrial decline and united by a desire to embrace fresh sounds, electronic or otherwise, the pull of a bold and bright future seemingly just around the corner felt suddenly very prescient.

It was the city’s nascent post-punk scene that first set the wheels in motion, laying the foundations for the imminent transformation of Sheffield’s rising music talent – or some of them, at least – into global superstars. With an explosion of futuristic sounds and the emerging technologies sparking an influx of synths and electronic equipment, it felt as if anything was possible.

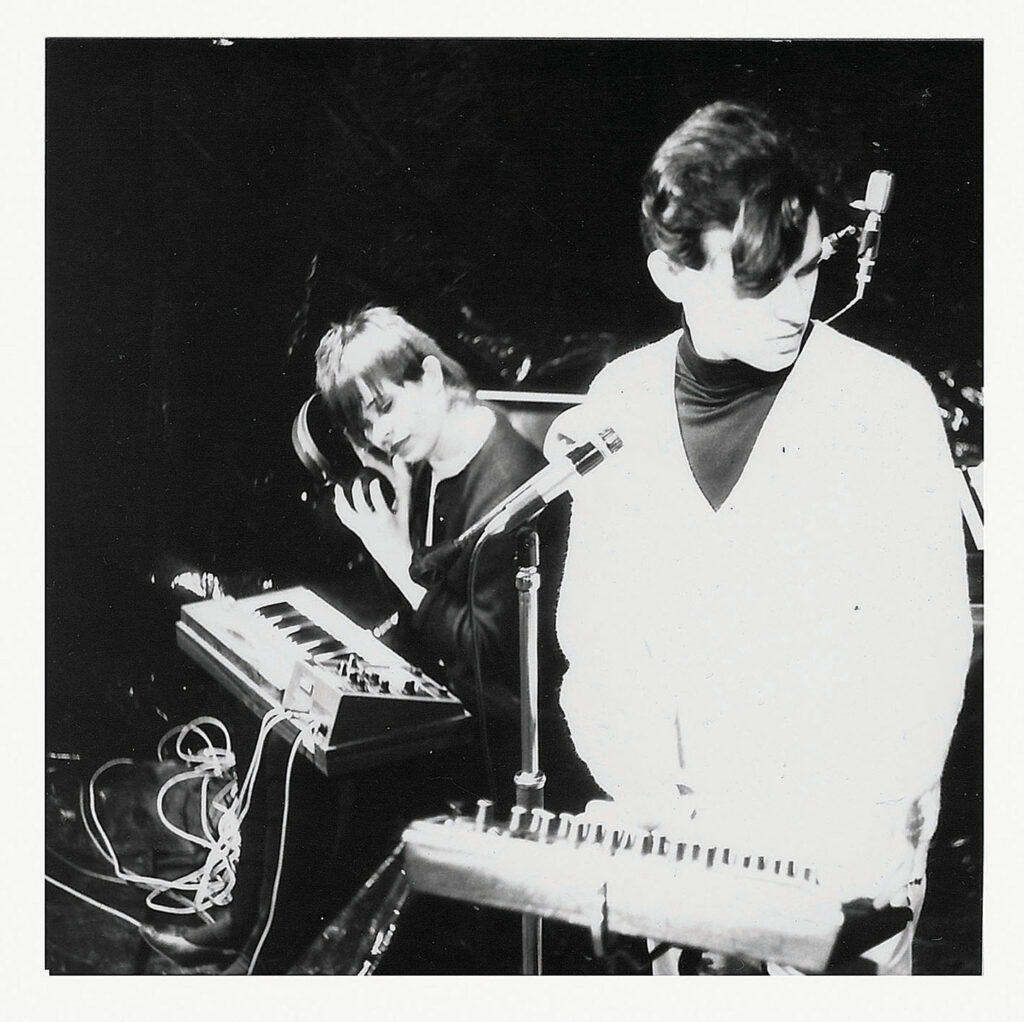

Just one of the many fledgling groups striving for recognition in late 1977 and early 1978, Vice Versa considered themselves modern-day synergists for electronic sound. Fuelled by the gung-ho spirit of punk, and desperate to immerse themselves in a world that was rapidly accelerating around them, Mark White and Steve Singleton, who were joined by David Sydenham, hurtled headlong into Sheffield’s fast changing cultural mix.

“We just needed to express ourselves,” says Steve Singleton. “David Sydenham was my school friend. When he got thrown out of his parents’ house and had nowhere to go, he came to live with me. Part of the deal was that he had to learn an instrument and start the band with me.”

White and Singleton are here to talk about the long overdue Vice Versa box set, ‘Electrogenesis: 1978-1980’, which celebrates the group’s legacy and long-neglected contribution to the electronic milieu. Taking in studio sessions, official releases, unreleased material and live recordings, all fizzing with the requisite restless energy and youthful abandon, it’s a beautifully packaged, painstakingly restored, comprehensive retrospective, brilliantly capturing the core essence of what the pioneering pre-ABC combo were all about.

Pitched somewhere between the distorted rhythmic bleakness of classic Cabaret Voltaire and the edgy, avant-garde analogue slant of early Human League, there were already traces of proto-electronic pop creeping through in Vice Versa’s sound, particularly on the icy, resonant synths of ‘New Girls/Neutrons’ and the infectious, minimal wave fizz of the wonderfully raw and defiant ‘Riot Squad’. Featuring White on vocals, sounding wilfully detached and machine-like, both tracks were included on the group’s 1979 debut EP, ‘Music 4’, which was awarded ‘Single Of The Week’ by the NME. Back in the here and now, White and Singleton are getting a real buzz from revisiting Vice Versa.

“It’s just like when we first started doing it and it was like, ‘Hey, let’s be in a band’, even though we couldn’t play very well and didn’t have much equipment,” says Singleton. “We were into ideas and experimenting. We always did it for fun, to amuse ourselves.”

They were exciting times, arguably the last truly great defining era of music.

“We were very much influenced by Bolan, Bowie and Roxy Music – the holy trinity,” remembers White.

But a few years or so before that, the punk ethos still prevailed. White and Singleton had first met when they were 16, at the Top Rank Suite (now Sheffield’s O2 Academy).

“Yeah, Mark gravitated towards me,” recalls Singleton. “When I think back, the punks were so few in number, you could practically name them all. And all those people then formed bands, but in Sheffield they didn’t form punk bands, they formed different types of bands, bands influenced by punk.”

“Steve had a punk fanzine called ‘Steve’s Paper’,” says White. “So I approached him and said, ‘Can I put an ad in your magazine? I’m trying to start a punk band’. And Steve, without missing a beat, went, ‘I’ll be in your band’.”

Vice Versa started out as a group called Vital Outlet, “a mayfly thing, with a very short shelf life,” according to White. Eventually, seemingly more by accident than design, the VV sound began to emerge.

“We had absolutely no idea what we were doing,” he continues. “It was very much about fumbling around and finding something that worked. We discovered lots of little second-hand music shops in Sheffield. At that time, the working men’s club scene was huge and they’d often have organists on the bill, and the organists used rhythm boxes – du-du-tsch, du-du-tsch – and that would be like a bossa nova beat or whatever. We found that we could buy one of these things quite cheaply and I thought, ‘Let’s grunge it up and put it through a synthesiser – a patch thing – and make it go a lot harder’. It sounded quite good.”

“We got a Watkins/WEM Copicat [a tape echo unit],” adds Singleton. “It had three or four buttons on it and if you shoved two buttons in together, you could get a completely new sound.”

Heaven 17’s Martyn Ware and Cabaret Voltaire’s Richard H Kirk have often spoken about growing up against the backdrop of Sheffield’s industrial landscape, with the incessant, rhythmic thud of the drop forges, and how that affected their view of music.

“It’s a bit like Detroit,” reasons White. “I went there to meet Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson. When I landed, it felt similar to Sheffield. All the industrial infrastructure was falling apart – the Rust Belt and so on – and it’s really interesting that the music coming out of there had parallels with Sheffield.”

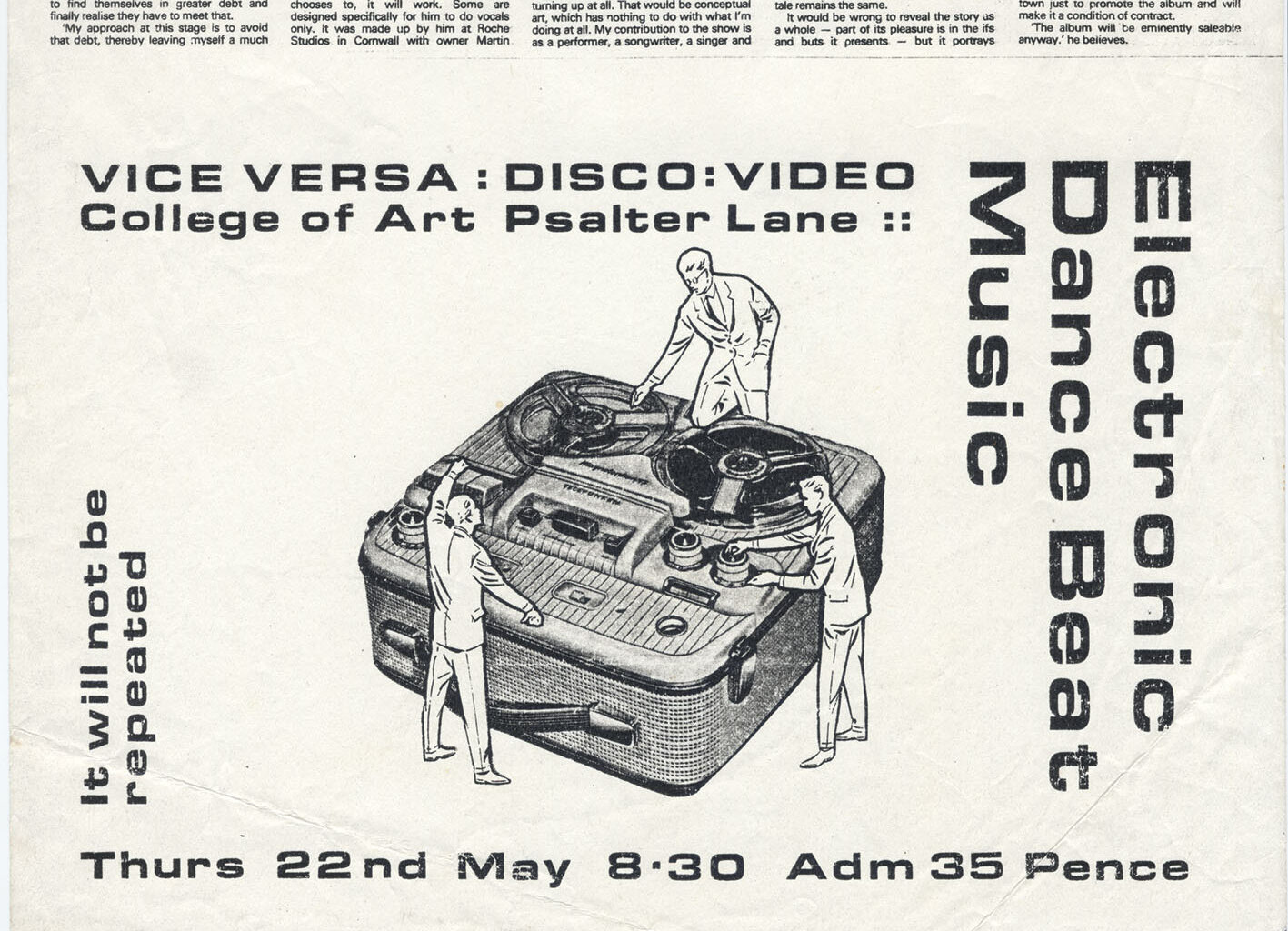

As well as taking inspiration from their surroundings, live performances quickly became another crucial building block. After Vice Versa’s inaugural show, supporting Wire in Doncaster in 1978 – “Beyond terrifying,” admits White – another key early moment was opening for The Human League at Sheffield’s Psalter Lane Arts College, the breeding ground for a whole host of acts linked to the city’s expanding electronic movement. At the time, the League were only five years or so older than White and Singleton, yet the age gap felt vastly more significant.

“We were boys, they were men,” says White. “They had proper jobs and they could afford these really expensive synths, which we were in awe of. We had just started to experiment with second-hand rhythm generators and synthesisers, but they had obviously been developing this in secret for years. It was like, ‘Oh, they’re writing hit pop music’. It sounded like it had come out of the future.”

“Zing, pomp, plink, here’s the future… brilliant!” quips Singleton. “Phil Oakey was married at the time and I’d never even had sex. He had a beard and I wasn’t shaving yet. I think they maybe looked down on us a little bit.”

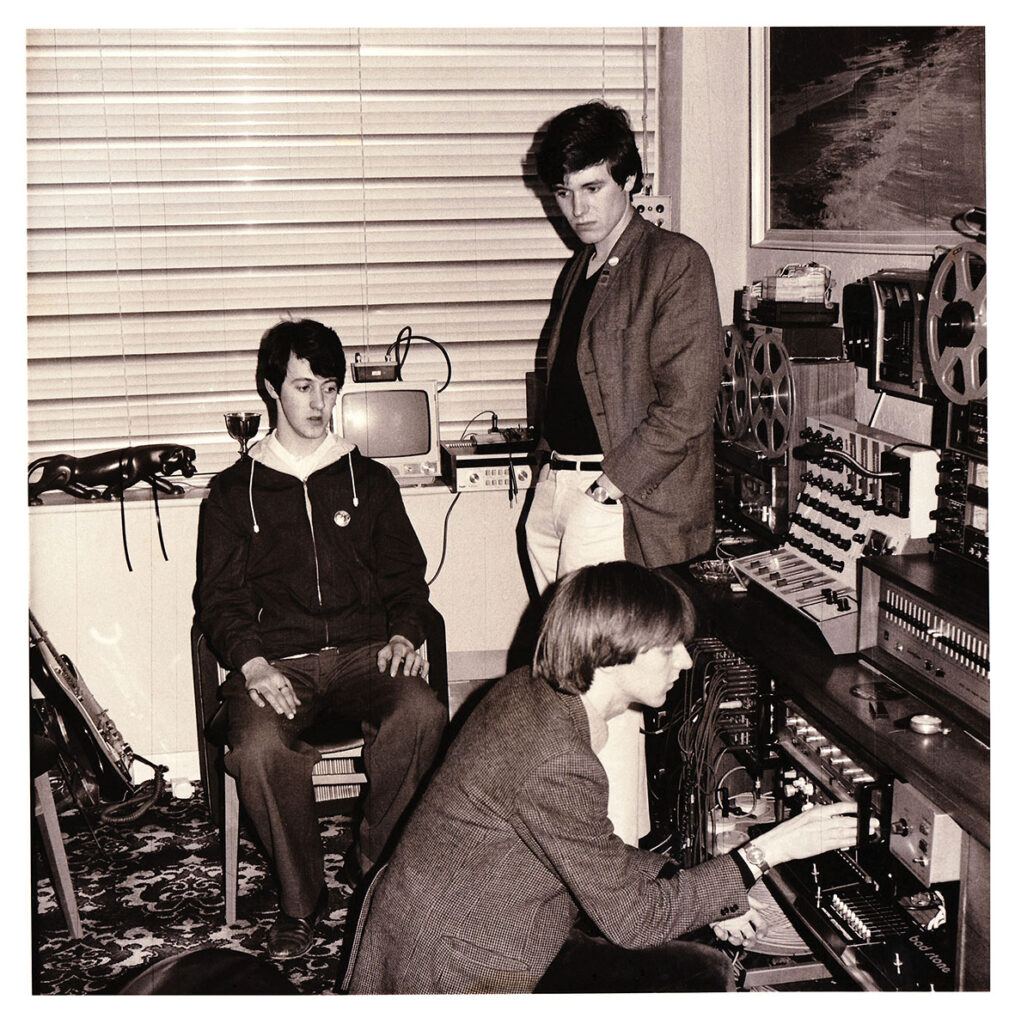

Undeterred and armed with plenty of ideas, youthful resilience and fearless chutzpah, Vice Versa were determined to make their way. An early ally was local producer Ken Patten, who helped them make their first record, the ‘Music 4’ EP, which was released in the band’s own Neutron label.

“On the grapevine, we had got to know about Ken’s Studio Electrophonique in Handsworth [an eastern suburb of Sheffield],” explains White. “He had experience of recording what he called ‘synthi groups’, one of which was The Future, an early incarnation of The Human League. His studio turned out to be a converted back room in a suburban house, where we had our first go at multitrack recording, which was enormously exciting. Ken was happy to let us do the production while he concentrated on getting everything down super clear. He coaxed great sounds out of quite basic equipment. Just about every Sheffield band ended up doing demos there – his studio became Sheffield’s Abbey Road.”

Following ‘Music 4’, Vice Versa appeared alongside fellow unsigned Sheffield acts Clock DVA, I’m So Hollow and The Stunt Kites on a four-band seven-inch EP called ‘The First Fifteen Minutes’. It was the second release on Neutron Records and suggests there was a large degree of cohesion and mutual support between some of the rising Sheffield groups. Is that a true reflection of how it was?

“We were all living in an extraordinary city, but we all had quite a different take on electronic music,” says White. “I remember having a chat with Phil Oakey and telling him I thought their music was amazing, really poppy. ‘Oh yeah,’ he said. ‘We wanna be like Abba’. I was like, ‘What? What the fuck?’. That really hadn’t occurred to me. And then there was Cabaret Voltaire, who were just a howling noise, a maelstrom.”

Vice Versa’s own take on the electronic genre has seen them cite touchstones such as early sci-fi movie soundtracks and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, as well as more mainstream sources.

“There was hardly anything else around,” notes White. “Then suddenly things started to creep out, like The Normal’s ‘TVOD’ and ‘Warm Leatherette’ – wow! – and Thomas Leer’s ‘Private Plane’, which we loved. Then there was Robert Rental and there was Simple Minds’ ‘I Travel’… there were so few of these records that you really cherished them. For me, it boiled down to Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’, Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ and Giorgio Moroder’s ‘From Here To Eternity’.”

“After ‘I Feel Love’, we thought, ‘Everything that’s gone before is over’,” says Singleton. “And then Kraftwerk were on ‘Tomorrow’s World’. It was like, ‘The future’s arrived – and we want to be part of it!’.”

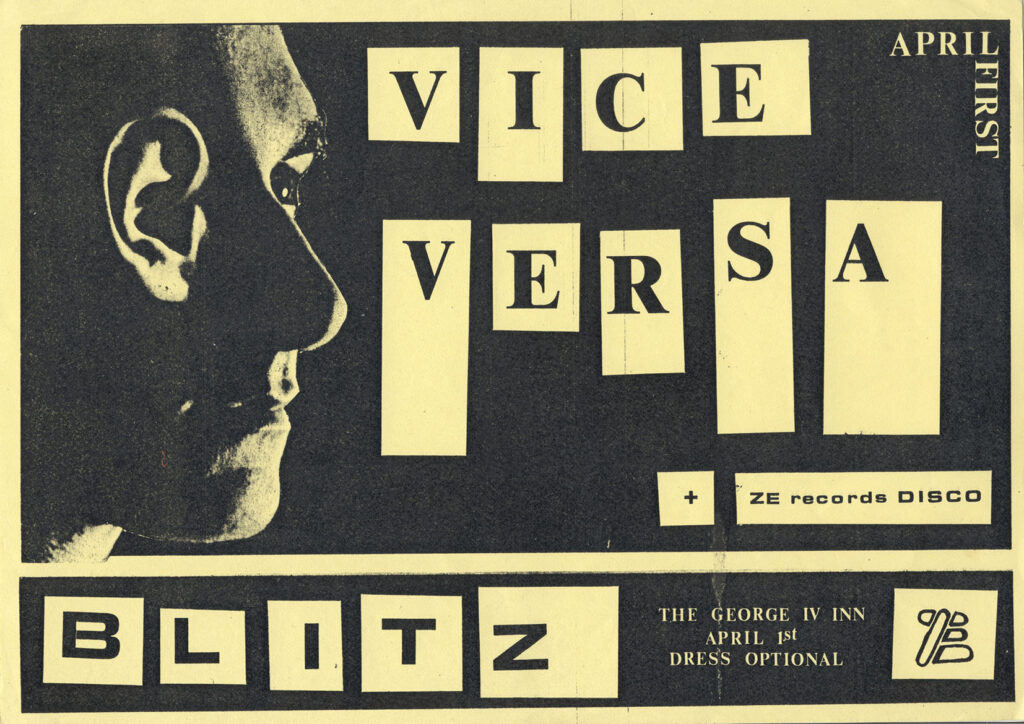

Everything changed with the arrival of a certain Martin Fry. Legend has it that he turned up to interview Mark White and Steve Singleton for his fanzine, Modern Drugs, and got on so famously with them that they asked him to stay. This was shortly after David Sydenham had left the band.

“The Sheffield scene was quite small, so you’d see the same people at the different gigs,” White explains. “We’d got to sort of recognising Martin, partly because he’s about six-foot-four and he used to wear a gigantic, floor-length leather coat. You couldn’t miss him. He came round to Steve’s, where we rehearsed, and we got on with him really well. In a moment of blinding inspiration, we said, ‘Martin, we’ve got a gig in two weeks’ time, David Sydenham’s left, he’s not part of the band anymore, and we need another member’.

“Steve’s uncle had made a little silver box with oscillators in it – it didn’t matter what the fuck you did, great noises came out of it – so we said to Martin, ‘When the spirit moves you, all you’ve got to do is press a few buttons and put the volume control up and down’. To his credit, because it must’ve been pretty scary, he went, ‘Yeah, I can do that’. The gig was a dream, and with Martin being so tall, it was the first one we ever got paid for on time. We just used to laugh constantly with him, he was always so funny.”

“Then we did a whole tour with him,” continues Singleton. “We played gigs right across the UK, supporting [new wave outfit] Cowboys International. When we got back to Sheffield, he was an integral part of the whole thing.”

The crucial moment, however, came when the trio were mucking about in the studio.

“At the time, we had this parallel ABC idea,” White divulges. “In our heads, we didn’t think it conflicted with Vice Versa and we thought we could do both. We were going to record some VV stuff for a Dutch label [Backstreet Records] in Rotterdam, and we’d heard a Bowie interview where he’d said that they’d all swapped instruments at the end of the ‘Lodger’ sessions, just to mix it up a bit and have a laugh, so we did the same. I ended up on bongos or something, Steve was on rhythm generator, and Martin took over the mic and started singing… and everyone in the room got the chills. He was so much more melodic and it felt right for our vision of what we wanted ABC to be. It was so the right thing to do, it was blindingly obvious.”

With Martin Fry ensconced in the group and the concept of ABC’s grandiose orchestral pop already a glint in their eyes, the days of Vice Versa’s nihilistic electronica most definitely felt numbered.

“We would be making Vice Versa music in the daytime, but then we’d go to certain nightclubs in Sheffield where they’d got into the 12-inch culture and the DJs had already started to learn how to mix,” reveals White. “We loved that. And then we had a Road to Damascus moment: we got into Chic.”

“We went to see them live and we had tickets at the side of the stage,” says Singleton. “They had a string section and they sounded very slick. We thought, ‘Imagine being able to do something as good as that’. They wrote songs about love, about going out to clubs and dancing. Just very uplifting music. So me and Mark started dancing. And Nile Rodgers saw us and said to the audience, ‘These two guys know what Chic is all about’. He came up and shook my hand, and then other people stood up and began to dance as well. It was great.”

“Nothing was quite the same after that,” adds White.

In essence, and in hindsight, Vice Versa were attempting to expunge what had gone before. There’s a great line in Eve Wood’s excellent 2001 ‘Made In Sheffield’ music documentary (to which Steve Singleton contributes) that perfectly sums up the late 1970s state of flux, where The Human League’s Ian Craig Marsh says, “We thought we were killing off rock ‘n’ roll.” Back then, did it really feel like they were breaking new ground?

“It seemed so old hat to be mucking about with guitars,” notes White. “Electronic music felt so revolutionary – more so than punk.”

But as well as this, Vice Versa were also absorbed by linked artistic, creative and visual ideas and experiments outside of sound.

“We made music, but we were interested in maybe making collages, or having fun with the idea of a ‘futurist’ manifesto,” explains Singleton. “We liked Andy Warhol, we liked making screen prints, and we made video as well, before anyone else really got into it. I loved ‘The Man From Uncle’ and I loved that you watched the programme, then you could have the attaché case with the badge, the gun, the membership card, all the different bits in it. Those kind of things stayed with us.”

That aesthetic ethos is evident with the ‘Electrogenesis’ box set, which is an item of great beauty. Inside the box are four albums, a glossy LP-sized booklet, and a cut-out paper synth.

“It’s the story of what we did, which was pretty much untold because ABC came along and took over,” Singleton continues. “‘Electrogenesis’ is very much in keeping with the spirit of the time in which its songs were composed. The box set we’ve done is physical, not a download. It’s an artefact.”

Both White and Singleton insist there is no bad blood between them and Martin Fry, but they are no longer in touch with him and were concerned that Fry would disapprove of the box set.

“I didn’t think ‘Electrogenesis’ would happen because we never thought we’d be able to get the necessary permissions from Martin to do it,” says Singleton. “But Vinyl On Demand, who are putting out the box set, spoke to Martin – or Martin’s management – and he said, ‘Yeah, you can do it’.”

“Vice Versa: the band that morphed backwards,” chuckles White. “Vice Versa became ABC, so imagine if it changed back again, back to VV…”

Steve Singleton left ABC in 1984, while Mark White continued with the group until the early 90s. Since then, Singleton has worked in production and made an album of electronic music as Bleep & Booster, but White’s post-stardom movements have been pretty much shrouded in mystery – until now.

“I realised I had contributed all I could to ABC and I needed a rest after 15 years of constant work,” he admits. “I’d achieved all my musical ambitions. I felt like I’d eaten a full box of chocolates and I never wanted to see another chocolate again. So I took three years off, relaxing in silence at ashrams in India and having long brunches on Westbourne Grove in London.

“I didn’t listen to any music at all for three years,” he continues, his voice almost a whisper. “I didn’t even have a radio in the car, I had it taken out. The only thing I’d listen to then was Indian devotional music. I just wanted ‘Shhh’. I read every self-help book there was and then discovered I had a talent for Reiki. Over a period of years, I trained to be a Reiki master and started a Reiki centre in Notting Hill.”

Despite this peace and quiet, White has thought long and hard about taking Vice Versa out on the road and playing live again.

“Oh, yeah,” he answers instantly. “I think it’ll happen. And I’m trying to persuade Steve that we should do an ABC song and give it the VV treatment.”

Reviving Vice Versa has also got them thinking about how things used to be.

“Back then, we’d just bang ideas out,” explains Singleton. “When you’re younger, you do things without really thinking. We were doing things for fun.”

“When you’re young, you’ve got less fear of failure,” concurs White, although it’s worth pointing out that both he and Singleton still seem to have some of that youthful fearlessness about them.

“We’re still punks in a way… electro-punks,” quips Singleton.

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

So are we likely to see new Vice Versa material anytime soon?

“We’ve been working on new stuff for about a year,” reveals White. “We’d probably describe it as what [revered German/American architect] Mies van der Rohe would do if he could handle a Moog modular system, or if Detroit techno had a sense of humour.”

Looking back, does it seem almost incomprehensible that so much successful mainstream music evolved out of that early, often difficult Sheffield-centric sound?

“No,” replies White. “I think everybody had ‘Top Of The Pops’ or some form of world domination at the back of their minds.”

“By the time ABC got to ‘The Lexicon Of Love’, we felt we wanted to make something of note,” says Singleton. “We wanted to show everybody else what we were about. That was the good thing about Sheffield – it was competitive. We were up against The Human League, Heaven 17, Cabaret Voltaire, Clock DVA…”

“I remember when [Heaven 17’s] ‘(We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang’ came out in 1981,” adds White. “We were just going through our VV to ABC transformation and I thought, ‘Fucking bastards, they’re on the same groove lines here’. But I’ll go on record now and say that I am prouder of this box set than of anything else I’ve done in my career – including ‘The Lexicon Of Love’.”

The future, once again, suddenly seems rife with possibility.

“I think Vice Versa should be on ‘Later… With Jools Holland’,” beams Singleton. “Maybe one week when they couldn’t get Tom Jones on or something.”

“Yeah, but I wouldn’t want Jools jamming along with his fucking boogie-woogie,” White interjects, vehemently. “Unless he did it on a Korg MS-20, of course.”

‘Electrogenesis: 1978-1980’ is released on Vinyl On Demand

RIP David Sydenham

We were sorry to hear that David Sydenham, the original third member of Vice Versa, recently passed away.

“I’d got back in touch with him early last year,” explains Steve Singleton. “He was a hard man to track down. As well as being a founder member of Vice Versa, we had gone to the same school together and we shared a love of music and fashion. He was a first generation punk rocker. He was the Pitsmoor Punk.

“It was fabulous to meet up with him again after around 30 years, to reconnect and talk about the ‘Electrogenesis’ project. He wasn’t in great shape, but he was really proud of the box set. David ended 2014 on a positive note, he was in a good place, he had hope for the future, and he was happy to have been one of the original ‘electronic soul brothers’.”

“I was very shocked and saddened to hear about David’s passing when Steve told me – it came out of the blue,” says Mark White. “I will always remember how he welcomed me into VV in the early days, sharing the excitement of the post-punk boom of that time.”

In the late 1970s, with music beginning to change beyond recognition, there was increased fascination and curiosity about all the new kit coming onto the market.

“The Korg MS-20 was the first proper grown-up synth that we saved up to buy,” recalls Steve Singleton. “And there was the Korg M500 Micro-Preset too, which had white and pink noise.”

It could also do very early sequencer-type lines if you got it to arpeggiate,” says Mark White. “If you held a couple of keys down, it did a self-generating loop, and you’d have to play with that in time. That was a huge step forward. But nothing synced together – there was no programming as such, so it was kind of ‘live’.

“We were still very influenced by that punky energy then. As much as we loved Kraftwerk – and still do – a lot of the early Vice Versa songs were quite punk. Even when I listen to them now, I still hear The Ramones playing and singing in the background.”