There was no single unifying event for the formative UK electronica scene, no point when something suddenly clicked, no precise year zero moment. But there was a bunch of like-minded souls beavering away in what they thought was their own little void, unaware there were others just like them all over the country. We talk to seven of the artists featured on the ’Close To The Noise Floor’ box set and get their big bang stories

John Foxx

Ultravox!

“The first piece of kit that I used to create an electronic noise was a theremin. It was made from an adapted transistor radio by a friend of mine in Chorley, Lancashire, when we were still at school. This was 1963 or 1964. It really howled and you didn’t even need to touch it. I was truly impressed. The future was right there.

“While Ultravox! were seen as a post-punk band, our records were always full of synths. Even when we were experimenting with feedback and extreme amp sounds, the synths were there along with the guitars. ‘My Sex’, on our debut album in 1976, was the very first synth ballad.

“For us, Neu! were certainly an early inspiration. ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’ on ‘Ha! Ha! Ha!’ was our first use of a drum machine and it created a new template for bands: synths and drum machines with heavily treated guitars. I’d decided electronics was the future just before that point. That’s when I began writing ‘Systems Of Romance’, followed by ‘Metamatic’. We worked with Conny Plank on ‘Systems Of Romance’. He was about 10 years ahead of anything else at that time. Conny was future central, all roads to anywhere interesting ran right through his studio. What a man.

“I’d met Brian Eno just after he’d left Roxy Music and he worked with Ultravox! on ‘Ha! Ha! Ha!’, supplying encouragement and ideas, as well as synths and an early drum machine. There was a lot of common ground, from ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and German electronica, to finding some sort of future language for music and throwing all the old rock clichés overboard. For most British musicians, there was only rock, pop, jazz and classical during this period. If you didn’t fit any of those rigid categories, then you were dead. But we were determined to devise some sort of music away from ‘Top Of The Pops’, something that was a real sonic adventure.

“Eno turned out to be a great galvaniser and an enthusiastic reinforcer of ideas. He was just right for us then. I don’t think anyone in Britain was doing anything remotely similar to us, this was 1976 after all, but from around 1978 onwards, there was a succession of new names being talked about – The Human League, Cabaret Voltaire, Daniel Miller and Thomas Leer. Mercifully, everyone seemed to be different enough to create their own territories without a tussle.

“After years of feeling completely isolated and not sure if we were perhaps nuts, it seemed there was something in the air. It felt like some sort of tide was building. And then in 1979, Gary Numan came out with that great record and the entire thing went overground in a rush. It was one of those moments when everyone recognises a new thing and we suddenly felt confirmed in all that blind, isolated chance-taking.

“And with that, the music world changed overnight. After Numan, we were all suddenly in and everything else was out.“

Martyn Ware

The Human League / BEF / Heaven 17

“I first met Ian [Craig-Marsh] at a council-run arts project in Sheffield called Meatwhistle. It was run by two actors, Chris and Veronica Wilkinson, in a building round the back of the City Hall. It wasn’t just drama, they had an early video camera and some musical equipment too, and they encouraged us to be creative. It’s also where I met Glenn [Gregory] and Ian Reddington, my actor friend who was in ‘Coronation Street’. I’m eternally grateful to Chris and Veronica because that place changed my life.

“This was 1975-ish and you couldn’t imagine being a musician for a living. What did I want to be? Not a bloody clue. Ian and I got jobs as computer operators for different companies. Back then, a computer had the same processing power as a digital watch from a pound shop has now. They were in giant rooms doing things like payroll. I used to be a trainee manager at the Co-op so it was preferable to boning bacon, believe me. I liked the idea of working with computers and at least it meant I was facing the future.

“Ian and I started messing around, making up groups. We had a small audience within Meatwhistle, but our imaginary world was a bit like Andy Warhol’s Factory. We’d hire rehearsal rooms, dirt cheap former engineering shops in the city centre, and we thought it was so cool because they were post-industrial buildings. We’d have big parties in these horrible, filthy places and it all seemed kind of edgy and fun.

“The first thing I bought was a dual stylus Stylophone. That was me thinking I was Eno. After that, Ian bought a Maplin kit to build a synthesiser, but all it could do was kind of motorbike sounds. It had a matrix of about 120 switches on it, of which only five worked. You couldn’t play any melodies with it, but it looked great. When Korg and Roland started producing entry level synthesisers, it coincided with us being old enough to get some financial credit, so we clubbed together and bought a Korg 700. It was £350 if I remember rightly. It was either that or get a second-hand car.

“The Korg led to us experimenting more, but it was just mucking about really. A bit later on, I read an article about Eno saying all you needed to have for your own recording studio was a two-track machine you could bounce from track to track on, sound on sound. So we bought this Sony machine and that’s how we recorded ’Being Boiled’. The next thing we know, we’re signed to Fast Records in Edinburgh and John Peel is playing it. Then we got signed by Virgin and the rest is history.

“So ’Being Boiled’ was recorded in a disused factory on a domestic tape recorder for £2.50, the cost of the tape. We didn’t have a mixing desk, we didn’t have any EQ. We had nothing. It was literally bouncing from track to track and stopping when the degradation got too bad. Everybody says, ’Oh, we love the minimalist simplicity’. We couldn’t do anything else really.“

Chris Carter

Throbbing Gristle / Chris & Cosey / Carter Tutti

“When I was quite young, about 11 or 12, my father bought me a small, portable tape recorder. I also had a transistor radio, so I used to record off the radio and cut the tape up. My parents then got me those little electronics kits you used to be able to buy kids, and I would build crystal radios and oscillators. It all started from there. I used to buy Practical Electronics magazine and I built my first synth in around 1975.

“I was a prog rocker at the time, into Tangerine Dream, Genesis, The Nice, all the usual stuff. I used to go to lots of gigs but no one seemed to be making the kind of sounds I had in my head. I liked the idea of being on stage and giving people a different experience, so I developed this sort of one-man show with my custom-made instruments. It was basically me doing this droney ambient music with some friends projecting visuals for me. We used to travel all over the country doing stuff.

“There was a really interesting DIY thing going on during the mid-70s, which was partly born from Practical Electronics. They used to publish synth circuits, quite a lot of them, and I knew at least half a dozen people who were building homemade synths and modifying these published designs. A good friend of mine was [visual artist] Bruce Lacey, who sadly passed away recently. We got into swapping circuits and he showed me how to build my first filter. There were lots of little groups of people swapping circuits and ideas and building all this stuff. I can think of at least three or four friends who built fully fledged modular synthesisers and some of us were performing with them.

“Throbbing Gristle played at the YMCA on Tottenham Court Road in London in 1980. I remember it well. It was quite a big thing, quite an unusual event. In fact, it took place over a couple of nights and there was some really oddball stuff on the bill. It was a real mix of different bands – Joy Division, Echo And The Bunnymen, This Heat – and no one had heard of most of them. You could feel something exciting was happening, though. It wasn’t rock ’n’ roll, that’s for sure.

“There was a crossover period in around 1981, where Cosey and I were doing Throbbing Gristle and just starting Chris & Cosey. Our sound changed pretty radically at that time and we adopted the house style that we’ve still got now. It’s funny because we were offered a big worldwide tour with Grace Jones in 1981, but we had to turn it down because Cosey was pregnant. They gave it to Blancmange instead. If we had taken that Grace Jones tour, our career path might have gone on a different trajectory. But we were very happy, Cosey was pregnant, we were going to move out of London and settle down in the country, and we thought, ‘No, we don’t really need all that right now, let’s do it to our own timetable, not someone else’s’. So in a parallel universe, we could be like Depeche Mode.“

Martin Bowes

Attrition

“I make music because of punk. That was the initial spark for me. The first thing I did was a fanzine called Alternative Sounds, which I started because there wasn’t one in Coventry at the time. It lasted for two years, 18 issues, during which time the 2-Tone scene exploded in the city. I got to meet lots of musicians and after a while I decided to bite the bullet and start a band of my own. So I hooked up with Julia Niblock [later of The Legendary Pink Dots] and we formed Attrition, which is still going today.

“A big turning point for me was seeing The Human League supporting Siouxsie And The Banshees. It was one of the best gigs I’ve ever been to. I’d never seen an electronic band before and it was brilliant. They totally blew my mind. I’d bought Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ single a few years earlier, but only because it was a hit in the UK. I didn’t really know much about them or that whole German electronic scene. I didn‘t really know Neu! and Tangerine Dream were just hippies as far as I was concerned. But then one night John Peel played ‘Showroom Dummies’ in the middle of a load of punk stuff and I thought, ‘Bloody hell, this is great’. Then when I saw The Human League, it all started to connect up.

“Attrition were originally a guitar-bass-drums band – I used to shout a lot and scrape the guitar with a brick and stick it through delays – but we got a synth after a few gigs, a little Wasp, and that was it. We sacked the drummer and got a drum machine too. We’d mess around with other bits of kit as well. I remember taking a tape machine and extending the tape round a chair to get a really long loop and recording some American preacher onto it with little clicks every time it went round. Nobody told us what to do, there weren’t any YouTube tutorials to watch, so we just tried whatever daft ideas came into our heads.

“The Attrition track on the ‘Close To The Noise Floor’ compilation is an extract from our first album, ‘Death House’. I shared a house with a guy who ran a cassette label, Adventures In Reality, so he put the album out. There were only two tracks on it. The first was an improvisation inspired by ‘The Night Of The Living Dead’, which we did one afternoon. We did another improvisation the next afternoon so we could put something on the other side of the tape. This was in 1982. I think we sold around 500 copies.

“Later on, I started working any job I could find so I could save up money to buy more gear and better gear. In the end, I was able to put together my own studio, The Cage, which I’ve run since 1993. I’ve worked on everything from Nine Inch Nails to Coil to Merzbow here, but it’s all very different to how it used to be. I just wish I could still do an album in two afternoons. It takes bloody ages these days.“

Andy Mccluskey

OMD

“The reason Paul [Humphreys] and I started listening to records together was I had a mono Dansette record player and he’d built himself a stereo. So we’d been on this musical journey before we’d even started making music. I was buying records on a Saturday morning and going round to Paul’s house to listen to them on a Saturday afternoon.

“As soon as I heard Kraftwerk, that was the key, but we were two kids who a) couldn’t afford expensive synthesisers and b) could barely play anyway. But when Eno started doing his solo albums, the fact that he was getting weird noises out of conventional instruments made us think, ’We can do that’. To start with, we just had a bass guitar and a load of stuff we made ourselves. We did very weird ambient music, because that was all we could do. We didn’t even have a keyboard we could play a tune on.

“Our first step up from completely ambient music was ‘Almost’ [‘Electricity’ B-side], which is a really simple song. Paul made the drum unit himself. He took the circuit diagrams from a drum machine and made a bass drum, a snare drum, white noise and a hi-hat, and connected them with metal rods onto copper pads. You know the long red and black connectors you get on electronic voltage test meters? That’s what we were using as our drum sticks.

“The synth melody on ‘Almost’ is a Korg Micro Preset we bought from my mother’s mail order catalogue. It was incredible, £7.36 a week, so it was like, ’Hang on a minute, we can actually afford one of these’. Admittedly, it wasn‘t much better than a Stylophone because every preset – Trumpet1, Trumpet2, Violin1, whatever – just went ’eer’. It was an entry-level electronic keyboard with a really primitive sound module, but at least we had a synthesiser, and we pushed it to its extremes to get something interesting out of it.

“At the time, artists like ourselves, The Human League, Daniel Miller and a few others, were all working in our little vacuums. We were taking influences from similar things, but none of us knew the others were there. I remember Paul and I were standing in Eric’s Club in Liverpool in the summer of 1978 when the DJ played this piece of music and I went, ‘What the hell is that?‘. So I asked the DJ what it was and he said, ‘It’s “Warm Leatherette“ by somebody called The Normal‘. I went back to Paul and said, ‘OK, we need to stop writing songs in your mother’s back room and actually get on stage‘.

“The first gig we did was at Eric’s that October, supporting a band we had never heard of. They were called Joy Division. The second one we did, we went to The Factory Club in Manchester and supported Cabaret Voltaire. So, you know, an interesting couple of first gigs.“

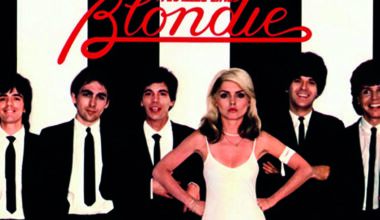

Neil Arthur

Blancmange

“I was at art college in Harrow when I met Stephen [Luscombe]. He had a mate in the graphics department. I was in this kind of post-punk art rock band called The Viewfinders at the time. None of us could play, but we made a lot of noise. We did covers of Shirley Bassey, Roxy Music and Frank Zappa, plus a few of our own songs, although none of them sounded like songs to be honest.

“Stephen was in band called Niru and the first time I saw them he was playing a saxophone connected to a Hoover on reverse thrust. Or it might have been a washing machine. Punk inspired lots of people, not just musicians, to express themselves in different and often unconventional ways, so Stephen and I got talking about making noises and we said, ‘Why don’t we get together and see what happens?‘.

“Stephen had this old four-track recorder that he’d borrowed and we got some Tupperware and an empty tin of Smash, that powdered mashed potato. We put foil on the top of the tin and hit it with little paint brushes. We slowed the machine down when we were recording, but then played it back at normal speed and it sounded really nice. So we just started making these soundscapes. Stephen would sometimes talk over the top of the recordings, passages we found in books or lyrics written by friends, and it all started to develop from there.

“All the synths on ‘Happy Families’, our first album, were borrowed. We didn’t own a synth until we did ‘Mange Tout’, the second album. In the early days, we borrowed an ARP Odyssey from Cliff Fox, a mate of ours who was in a band called The Models [who spawned Rema-Rema and The Wolfgang Press]. He was on the foundation course when I was doing my degree. We just used the ARP to make sounds for textural backgrounds. We didn’t think there was much point in us doing anything else with it because it wasn’t ours.

“Another mate of mine, Mark Cox, who was in Rema-Rema, was always really encouraging. He lent us his rhythm unit, and it was one of those with rock, slow rock, rock1, rock2. That’s when we started doing things like the early versions of ‘Sad Day’. And then Stephen got this organ. He didn’t buy a synth, he bought an organ with preset sounds and a rhythm unit. This was when we did ‘Holiday Camp’, which is on the ‘Close To The Noise Floor‘ album. It‘s from our first release, the ‘Irene & Mavis’ EP.

“For me, punk was like a perfect storm. One reason it came along was as a reaction to prog rock and I was never a fan of prog. The synths those groups used were never on my radar, but the synths used by Eno, Bowie, Kraftwerk and Sparks most definitely were. We thought, ‘If we can make our instruments sound a bit like anything from “Another Green World“ or “The Man-Machine“ or the first two Roxy albums, then we’re moving in the right direction‘.“

Andrew Lagowski

Nagamatzu

“For me, it was always the machinery first. I was a drummer in a band when I was at school, which was brilliant, but things changed when my father bought a reel-to-reel tape machine from the local hi-fi shop. It was a professional job, a Ferrograph Logic 7, and I got the bug for recording anything and everything I could with it. The first thing I recorded was a regression, a guy being hypnotised and regressing back through his past lives, which I did for Radio Orwell, our local radio station in Ipswich.

“I’d read about John Cage and his table full of electronics and I loved what Chris Watson was doing in Cabaret Voltaire, so I started chopping up bits of tape and experimenting with microphones and a kid’s keyboard. But then I remember thinking, ‘I want to be Richard Kirk, I need to get a guitar’, so I bought a second-hand guitar and this horrible old fuzz box. The guitar cost £30. I never managed to play it properly. I had to re-tune it so it was easier for me.

“A lot of what Nagamatzu did was just experimenting and seeing what noises we could come up with. I was really into Whitehouse and Throbbing Gristle and Nurse With Wound. I used to write to William Bennett from Whitehouse. We had a long correspondence. Stephen Jarvis [the other half of Nagamatzu] was more into stuff like Joy Division and Bauhaus, but he’d never been in a band before, so it was very new for both of us. I think we latched onto the misery of the early goth thing and we had the raincoats and the floppy fringes. Everyone in Ipswich seemed to be into heavy metal, so going out was often quite tense. We’d get called all sorts when we walked down the street.

“Most of the equipment we used was borrowed from other people – synths, pedals, whatever we could get. We were straight out of school, so we couldn’t afford to buy gear of our own. When we did our first album, ’Shatter Days’, which came out as a cassette in 1983, a lot of the equipment belonged to John Bowers, who’s now in Tonesucker. We did it on John’s four-track, which he brought round to my house. I did try to build a few effects pedals along the way, but nothing like Chris Carter. I’m not that clever. I had a Meccano set as a kid and I was very good at building things that looked interesting but didn’t work.

“I’ve done a lot of solo records since Nagamatzu stopped in the early 90s [working mainly as Lagowski, Legion and SETI] and they don’t really sit into a particular genre, but there’s often a slight quirkiness about them. I’m working on an eight-hour album called ‘Sleep Environments For Interplanetary Travel’ at the moment, which I want to release on a micro SD card so you can listen to it all the way through in one go. Just as well we don’t have to release stuff on C-60s now.“

‘Close To The Noise Floor – Formative UK Electronica 1975-1984’ is out on Cherry Red