Sleep-deprived – thanks to a flight that required getting out of bed at three in the morning – is probably the best way to discover a new city. It heightens the sense of dislocation. We’re on our way to Düsseldorf, on a mission to find its pulsing electronic heart, as described by the multitude of voices in Rudi Esch’s book, ‘Electri_City: The Düsseldorf School Of Electronic Music’.

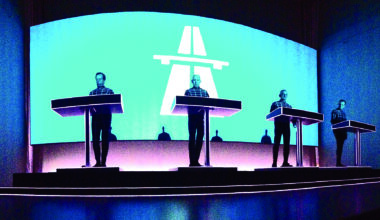

For many years, the myth of Düsseldorf has swelled in the imagination of the electronic music aficionado: the home of Kraftwerk, where they laboured with their machines under neon lights in Kling Klang, stopping only to visit a nearby coffee shop to discuss modernism and the European project while eating cake. Where, as Wolfgang Flür once jokingly told me, Kraftwerk’s music is piped from speakers on every street corner.

Conny Plank’s studio was in nearby Wolperath. Actually, it’s about 40 miles from Düsseldorf, but in 1974 he packed his VW van with recording gear and drove to Kraftwerk’s rehearsal studio to record ‘Autobahn’. If that doesn’t count as a significant Düsseldorf moment, nothing does. Eno and Bowie found inspiration for ‘Low’ from the likes of Neu! and Conny, and in time Eno made a Harmonia album with Moebius and Roedelius – neither from Düsseldorf, but a part of its orbit nonetheless, thanks to Roedelius’ relationship with Florian Schneider’s sister, Claudia (more from her later) – and Michael Rother, a Düsseldorf chap at heart. Rother was, after all, in D-dorf’s Number One rock ’n’ rolling groovers Spirits Of Sound with Wolfgang Flür in the 60s. And he was in the three-piece Kraftwerk line-up when Ralf went back to architect college in 1971. And he was in Neu!, of course. And then there was the band that blueprinted the future of a good chunk of half-decent late 1970s outfits, La Düsseldorf. Later there would be Liaisons Dangereuses, Der Plan, DAF, Die Krupps, Propaganda, Mouse On Mars… the place must be built on an oscillator, it vibrates with such electronic energy.

To their credit, the City Council has realised that all this musical heritage has cultural value, and Düsseldorf is certainly focussed on its cultural status. Liverpool has The Beatles, Düsseldorf has Kraftwerk and a new branding for electronic music fans: Electri_City. The city’s bricks and mortar include Kling Klang, and the legendary clubs Ratinger Hof and Creamcheese. In fact, what with the reputation of D-dorf visual artists like Creamcheese regular Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Richter (whose work has broken the record for the most expensive piece by a living artist no less than three times, and whose painting ‘Kerze’ was used on the cover of Sonic Youth’s ‘Daydream Nation’), the architecture, the fashion industry and the associated photographers, all of which have intersected with each other and the music scene in one way or another, the city might just trump Liverpool.

The modernist Köln Bonn airport welcomes us to Germany. This is the airport where Devo would have landed in 1978 to make their debut album with Eno at Conny Plank’s studio. It’s where Ultravox would’ve touched down to make ‘Systems Of Romance’ around the same time. Gazing from the window of the Eurowings flight, we see the airport’s concrete structures, poured as per instructions from architect Paul Schneider-Esleben. Its main building is a pentagon, topped by a car park, surrounded on three sides by what look like vast ocean liners, attached to them are two enormous stars, where the arrival and departure gates are. On the internet, there is a website where people are discussing the design of Köln Bonn airport. Someone says the distance from the original location of the Ishtar Gate in Babylon to the end of the Köln Bonn airport’s runway 32R is 3,600km, and that the sum of the numbers one through 36 is 666. Someone else claims the airport is one of NASA’s Space Shuttle abort landing sites. The whole thread was started because someone asked if the airport was an Illuminati site. Was Florian Schneider’s father an Illuminati architect? Might this explain his son’s band’s abiding influence and power? (Hint: no he wasn’t, no it doesn’t).

Florian’s father set up his architectural practice in 1949, when his son was two. There was a lot of architecture required in post-war Düsseldorf, most of it had been bombed into ruins. Paul Schneider-Esleben would become a millionaire before too long. His first major commission was the Grußgarage car park. When he presented the finished structure with its glass facade to the client, they asked when the cladding was going on. The drawing he made of the internal structure is an object of restrained beauty, and the building itself – still in use as a car park – is listed. He was close to Joseph Beuys and many well-known artists, and he helped them land commissions from the wealthy captains of industry he was making buildings for. He also made jewellery, and gifted pieces to the women in his life. “Buildings are like children: eventually they go their own way,” he said when asked about the preservation of his work in 1987.

Once on the ground, we ask at an info desk where the train is that can whisk us to Düsseldorf with the German efficiency we expect. It’s on platform two. It’s not the Trans-Europe Express, but it will do. The train leaves on time, but soon slows to a halt and waits on the tracks for 15 minutes. Someone starts listening to horrible music on their smart phone. When we pull into Düsseldorf Hauptbahnhof, the sound of the train on the tracks does not resemble the opening white noise rhythm of Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’.

The station’s interior has been remodelled since the days when Ralf and Florian stood on the bridge over the tracks near to Kling Klang, listening to the rhythms the trains made, disappointed that they lacked the musical energy they were hoping for. The old ticket offices have gone, but platform 17, where Ralf, Florian, Wolfgang and Karl posed for the famous ‘Trans-Europe Express’ promo shot, is still there. The clock is round now. It used to be square.

“I realised that we needed a book, once you have a book then people start to take notice…” Rudiger Esch, author of ‘Electri_City: The Düsseldorf School Of Electronic Music’, is talking to me in Brauerei Schumacher, an eatery that’s about as German as it’s possible to get. Waiters refill our little 20cl beer glasses as soon as we drain them as we tuck into an almost surreal platter of pork joints, sausages and associated meat. It looks like an art installation, dominating the table with a serving knife and fork plunged into it. Portraits of stern-looking German patricians, presumably the lineage of the owners of this long-established, impossibly Germanic institution, look down on us.

The book, says Rudi, has provided the foundation upon which Electri_City can be built. The fact of the book’s existence legitimises all those hippies and freaks and punks and marginalised underground types who made the Ratinger Hof and Creamcheese such exciting places. Rudi, smilingly thick as thieves with the cultural attaché of the Düsseldorf council, is now as respectable as the city he wants us to love. And that’s why he has been able to pull together the two-day Electri_City conference of film, music and talks that brings us here, and it’s also why we’re off on a two-hour Kraftwerk-heavy tour of the city.

Our tour takes in the locations of both Ratinger Hof and Creamcheese, both now long defunct. Joseph Beuys energised the late 1960s scene, putting on “actions” at Creamcheese. “This is not a pub, it’s a total work of art,” said the renowned architect and curator Arnold Bode of the place in 1968. Now, as we stand admiring the building that used to house it, we are prodded out of the way by a large black BMW that wants to park right outside its door, it looks well-to-do, another residence or office for one of this city’s wealth creators.

It’s hard to imagine the scene that would have confronted us here when Kraftwerk played their debut gig at Düsseldorf’s own art freak-out space. It would no doubt have been every bit as wild as Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, or La Monte Young’s Dream House events.

“I am very proud of this building,” says Claudia Schneider-Esleben who has materialised out of nowhere as we stand in the shadow of the Mannesmann Hochhaus, the plain tower commissioned by the giant German steel (and later telecommunications) company. “It was the one of the first skyscrapers in Germany. My father made a lot of the furniture inside, but one day the management changed and they threw the furniture out of the windows. The people who worked there took it. Today, you can find one of his chairs in a gallery for €6,000.”

She laughs, something she does a lot. Is it the tallest office building in Düsseldorf?

“There is another one now, but there is always the architect’s competition, which is the highest penis in Düsseldorf?” She laughs again, suddenly and loudly. She points out the steel sculpture, by Norbert Kricke, in front of the building. “My father was always working with artists, and he asked for this to be made of steel. This was very typical in Düsseldorf, commerce and culture working together. This is a very rich town. They work a lot and earn a lot, and they like to show it. They like to collect art.”

“We grew up in a very cultural family,” says Claudia, who runs an art gallery. God, this family are smart. “Beuys was in the house. My father was friendly with Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.”

That explains Kraftwerk’s cultural depth, then…

“Yes, yes…” she says. “The big difference between my brother and other artists was that most of them were working class heroes, he was not. They were very jealous, because he had money to finance Kraftwerk. My brother started his education when he was nine, they saw his talent. He started with the flute, he had it made especially for him.”

Claudia played piano and was envious of her brother who could take his flute into the city and play with other people. “And I was a girl, so I had to stay home,” she says. This was the 1950s, of course. “There was a jazz scene, but electronic music? Nothing. Later, when it was flower power, we saw Frank Zappa and Jimi Hendrix. I had a good musical education!”

Does she remember Kraftwerk having their first hit with ‘Autobahn’ in America and the UK?

“Yes, of course,” she exclaims. “My father had hoped Florian would be a professor or something, but he didn’t finish his studies, neither did Ralf, and my father wasn’t happy. But when they did well with ‘Autobahn’, my father started to give presents of the album to friends!”

We walk as we talk, and soon find ourselves outside a pleasant residential building. “This is a biggie,” says Claudia. We’re on Berger Allee, just around the corner from the Mannesmann-Hochhaus, a street of grand looking houses. “This used to be where Emil Schult lived with Ralf Hütter,” she explains, from 1975 to 1985.

“Big parties with cakes, with some hash in perhaps,” she laughs. She’s gloriously indiscreet. We’ve wandered to the market. “Maybe we’ll meet Florian. He’s often there,” she laughs, again. What would her brother think of us walking around his old haunts, picking over the details?

“I can tell you what he said to me last year, ‘Why are you doing this to me?’ I didn’t give him any answer. He doesn’t like it.”

Well, Kraftwerk are such a mystery, of course people want to know more.

“They are very shy,” she offers. “They went to America and came back a success and their own country doesn’t give a shit, so it’s a kind of a protest. And when you are pioneers, you have to keep that position. It was the kind of Marlene Dietrich approach. They liked her attitude. Or The Residents. You keep it secret and people get even hotter, you know?”

In 1926, 7.5 million people visited Düsseldorf for the Great German Exhibition on the east bank of the Rhine, in the Golzheim district. It’s where the enormous CCD Congress Centre is now, where our little band of electronic music enthusiasts has gathered for the Electri_City conference.

We watch films. Mark Reeder’s ‘B-Movie’, documenting his life in Berlin as Factory Records’ representative there, is mesmerising. ‘Keine Atempause – Düsseldorf, Der Ratinger Hof Und Die Neue Musik’, features imagery of the legendary Ratinger Hof venue and clips of performance and interviews with DAF and Der Plan.

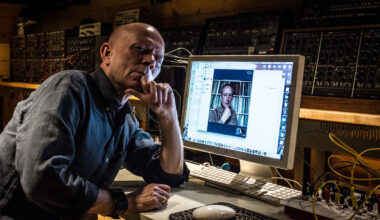

We listen to talks. John Foxx in conversation with veteran German music journalist Ecki Stieg, who is clearly emotional about finally speaking to one of his heroes. At one point, Foxx addresses the audience and directly expresses how upset he is Conny Plank has been sidelined by history. “He’s the most important music producer since George Martin,” he says, to warm applause.

Daniel Miller shares a panel with German DJ Chris Liebing, who describes his own connection to electronic music being forged by his discovery of Mute Records. Miller talks about his love of Kraftwerk and about the time he nearly got Klaus Dinger and Michael Rother to agree to re-release the Neu! albums on Mute Records. “Not only would they not be in the same room, they wouldn’t touch the same piece of paper,” he tells us.

We watch gigs. Over two evenings, we see Eric Random, one-time partner of Pete Shelley in the electronic duo The Tiller Boys, who turns in an invigorating solo turn, Marsheaux from Greece, John Foxx and Steve D’Agostino and their hypnotic and unsettling ‘Evidence Of Time Travel’ music and film show, London’s ornate Cult With No Name. Rusty Egan showcases his new album, and Jimi Tenor and Juri Hulkkonen perform a live film soundtrack.

It’s a strange, awkward love affair this. British music fans who were often out of kilter with the prevailing trends in their country found something beautiful and difficult in the music coming out of Düsseldorf. And the love affair continues, whether it’s Colin Newman and his memories of the art/music intersection of Ratinger Hof of 1978, Daniel Miller falling for Kraftwerk as Mute gestated in his subconscious, or Rusty Egan’s wholesale enthusiasm for the city and its music, something his irrepressible personality just can’t contain. Or our bewildered, impressed, exhausted demeanour as we eat the most delicious soup we’ve ever tasted in a Turkish fast food place at midnight, preparing to catch a bus to the airport at three in the morning, where the flight home is delayed by eight hours.

Düsseldorf seems to have an elastic hold on us. Do we have tickets for Kraftwerk at the Royal Albert Hall? Do you?

‘Electri_City: The Düsseldorf School Of Electronic Music’ is published by Omnibus