We’ve had 10 years of wonderful music and fabulous visuals from those genre-defining folk at Ghost Box Records and we’re popping corks with label co-founders Jim Jupp and Julian House to mark the occasion. Stand by for stuff about synths, sci-fi, Bagpuss, electromagnetic fields, alchemists, William Burroughs and haunted dancefloors

One of the most satisfyingly realised, visually interesting and admirably self-contained British independent labels since Factory, Ghost Box Records is celebrating its 10th anniversary this autumn. And they’re marking the occasion in typically restrained manner, with the low-key release of a ‘Best Of’ compilation, ‘In A Moment… Ghost Box’, and the latest in their ‘Other Voices’ series of collaborative seven-inch singles.

This idiosyncratically British imprint, co-founded by old school friends Jim Jupp and Julian House, is not so much a record label as an utterly immersive world-within-an-imaginary-world. Escape down their rabbit hole and enter a surreal, mystic, electro-psychedelic retro-future populated by wonderfully inventive acts that may or may not be singing songs that may or may not have been sung before. It’s fascinating, thrilling and bamboozling all at the same time.

We find the loquacious and easy-going Jim Jupp in deepest Sussex, sitting a room piled with cardboard boxes full of records at one end and a recording studio at the other.

“My desk in the middle of it all,” he laughs. “I’m literally balanced between the two worlds… and that’s how I like it.”

Reaching the 10-year milestone is not an insignificant achievement. So much has changed so quickly from a technological perspective in that time – and not all for the better if you’re a musician trying to make an honest living away from the corporate mainstream.

“Given the long run-up we had to getting the label started, it’s actually been longer than 10 years,” notes Jupp. “Both myself and Julian have been involved in music for a long time. I’d been in loads of bands, but it was always at the back of my mind that I should get my own thing going. But yes, 10 years ago was before easy access to internet distribution and too much file sharing, so it was a good time to start.”

The Ghost Box story isn’t solely about the music, though. There must have been a moment when they realised that their very specific aesthetic vision could only be realised by striking out by themselves?

“Julian and I go back a long way, although we weren’t in touch on a continuous basis,” says Jupp. “We were both living in London but we hadn’t seen each other for a few years, so when we did meet up it kind of reactivated a lot of the stuff we’d been interested in for a long time.”

What they were particularly interested in, and believed they had an instinctive feel for, were the cultural curiosities that switched on the generation born in the 1960s and 1970s – the public information films, supernatural children’s television programmes, and weird Penguin and Pelican paperback books that brought the esoteric fancies of fringe academics to wider audiences. It’s the sort of stuff that is deliciously lampooned by Richard Littler via his Scarfolk Council blog.

“We started digging around, finding weird fragments on the internet, and we were fascinated by how they resonated with people,” explains Jupp. “But we didn’t want to sound like the Radiophonic Workshop or produce images that looked like public information films or whatever, it was more about creating a world that could have existed, only slightly off or misremembered in some way. Almost a parallel world that existed elsewhere.”

And so the idea for Ghost Box began to take shape. Jim Jupp started building up his home studio, conducting early experiments for what would eventually become his musical offshoot, Belbury Poly. He found himself mainly drawn back to his old synths.

“I had a Yamaha CS-20M that I’d bought second-hand when I was about 15,” he says. “I’d gigged heavily with it with one of my bands, but miraculously it still worked… more or less. I’ve since had it repaired and spruced up. Despite its simplicity, it still gets regular use.”

Julian House was meanwhile thinking about how their new label might look. House is very much a latter-day Peter Saville, his distinctive work for the Intro design agency, where he still plies his trade, gracing many a discerning record collection. As well as being the visual provider for the whole Ghost Box roster, he’s designed sleeves for the likes of Stereolab, Broadcast, Primal Scream, The Prodigy, Oasis, Doves and many more besides.

For Ghost Box, House set out to create a visual palette that matched the peculiar musical otherworld that the label’s sound conjures. The idea of using a semi-subconscious pull of generationally shared cultural reference points that felt more than just an empty pastiche had been brewing since his undergraduate days at Central St Martins Art School in London.

We’re talking those jumbled up, half-remembered signifiers of four or five decades ago again – the 60s jazz and 70s folk sounds, the snippets of incidental TV music, the hazy scenes from entertainment shows and current affairs documentaries about nuclear war and domestic industrial strife. And perhaps above all else, the post-war sci-fi novels and TV programmes that juxtaposed a very British and very mundane kind of provincial life with the fantastical. All of this goes into the Ghost Box mixing pot and the result is quite a potion.

“The parochial stuff from the post-war period and how it’s overlaid with something either ancient and mysterious or extra-terrestrial and cosmic is a common thread for us,” agrees Jupp. “The weird impinging on the ordinary. It’s what Nigel Kneale and John Wyndham wrote about in ‘Quatermass’ and ‘The Day Of The Triffids’. It’s what a lot of ‘Doctor Who’ was about too.”

Much of this material is readily accessible now, even the preposterously obscure stuff. But a decade ago, in the days before YouTube, a lot of it only survived as vague memories.

“There was this perfect window to start our label, when the internet only really functioned as a means to open up possibilities,” notes House. “If you photograph something from a distance using a long lens, everything condenses into a flat plane, but the reality of that scene is far more complex and detailed. I think memory can work in the same way.”

The concept of sound collages working together with visual cut-ups was rooted in the inspiration House took from William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s ‘The Third Mind’, a book he discovered while still at college. It was the first publication to showcase the technique that Burroughs and Gysin popularised in the 1960s by taking text, cutting up the pages, and then reconfiguring the segments to form new narratives. Burroughs then adapted this approach for film-making with director Antony Balch, whose 1966 short ‘The Cut-Ups’ has been hugely influential on House.

And while the familiar graphic design discipline of applying brand consistency is present and strong with House’s Ghost Box work, there is also a characteristic wonkiness that separates it from anything else out there.

“Julian has always had very clear ideas about how it could all look,” explains Jupp. “When we started, we just had a simple website as a way to knock out a few hand-printed CDRs to a small number of like-minded people. Over those first few years, it seemed to grow organically into a legitimate record label. Which we never really intended to happen.”

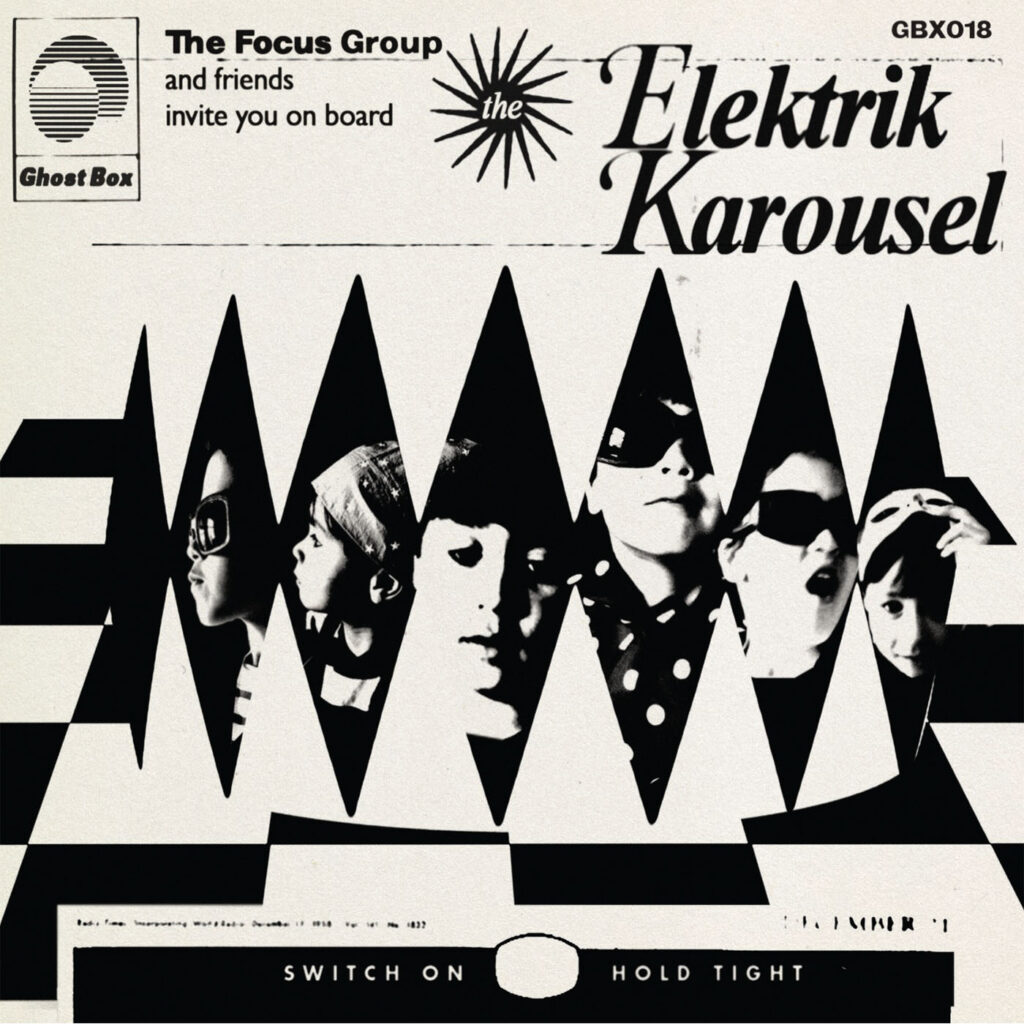

Alongside his design work, there’s also Julian House’s music. He began his sonic adventures as a teenager playing around with the music programme on his ZX Spectrum. He’d spool the sounds he created to make C90 tapes, though more in the manner of a surrealist than a turntablist. These days, he’s the man behind the dislocated mosaic sound of The Focus Group.

“Tape and film cut-ups always grabbed me,” says House. “Playing around with things in a way that you really shouldn’t, it’s like a form of magic. That’s the principle I’ve taken right through into The Focus Group. It all happens in a studio space, but it’s not something I could ever take out and play live.”

As well as the strong current of surrealism that runs through The Focus Group’s output, it’s easy to forget that much of the label’s brand of electronic music is at its core psychedelic.

“British psychedelia is a very big influence on us – and specifically its opposing forces,” admits House. “On one hand, it was debauched and transgressive, with all the reverb, effects pedals, synths and hallucinatory visuals, but then there were those naive, child-like pastoral elements too.”

There are elements of folklore weaved into Ghost Box’s complex audio tapestry as well. ‘The Geography’ by Jupp’s Belbury Poly project, which appears on 2012’s ‘The Belbury Tales’ album, is a real beauty in that respect.

“It’s about putting a fictional gloss on things that are well outside of any kind of academic sphere,” explains Jupp. “Julian and I grew up in South Wales and the landscapes – the Neolithic and Roman stuff – were all around us, but in terms of our experience and understanding of that, it came through oddball TV shows like ‘Children Of The Stones’. The same goes for the way that folk music was introduced into our lives. It wasn’t through listening earnestly to the Alan Lomax archive, it was through the folk music on programmes like ‘Play Away’ and ‘Bagpuss’. And whether or not there was a phoney aspect to it, that was all we knew because that was our culture in the 70s.”

So what do you get when you put electronica and psychedelia and folk together? In an article written not long after Ghost Box started, respected music writer Simon Reynolds dubbed it “hauntology”. Everyone needs a lucky break along the way, of course, and having the early support of someone like Reynolds was a huge help to the label.

“Oh, we’ve had lots of lucky breaks,” laughs Jupp. “But Simon Reynolds was certainly very positive about us in this big feature, which was in The Wire in around 2006. The article was about the idea of ‘hauntology’ as a music sub-genre based around a scene of sorts that included us and people like Moon Wiring Club, Jonny Trunk, The Caretaker and Mordant Music, all of whom were making this very distinctive British electronic music.”

Reynolds had indeed nailed the unique Ghost Box approach and he brought home the point in his ‘Retromania’ book when discussing the significance of ‘Caermaen’, another Belbury Poly track. By sampling a 1908 barrel-recorded folk song and changing its pitch, tone and structure to create an entirely new melody, Reynolds declared that the Ghost Box boss had effectively “made a dead man sing a brand new song”.

This notion of making dead men sing new songs neatly sums up what Jupp and House had seized upon when they started the label. And they knew that referencing specific residual aspects of their generation’s shared cultural history, however deeply buried they may be, would chime with similarly minded people.

“We certainly thought people of our own generation would get it quicker,” agrees Jupp. “We weren’t trying to create something from a specific era and we didn’t just want to attract white British blokes in their 40s, though. If you’re undertaking any creative endeavour and you’ve got a set of references and a respect for the source material, I think anyone can get it.”

These days, Ghost Box have a broad audience who clearly understand this strange, half-imagined creation that rings somehow true even if they didn’t experience it or remember it themselves. For those people, according to Jupp, Ghost Box “becomes an exotic otherworld they feel must have happened at some point”.

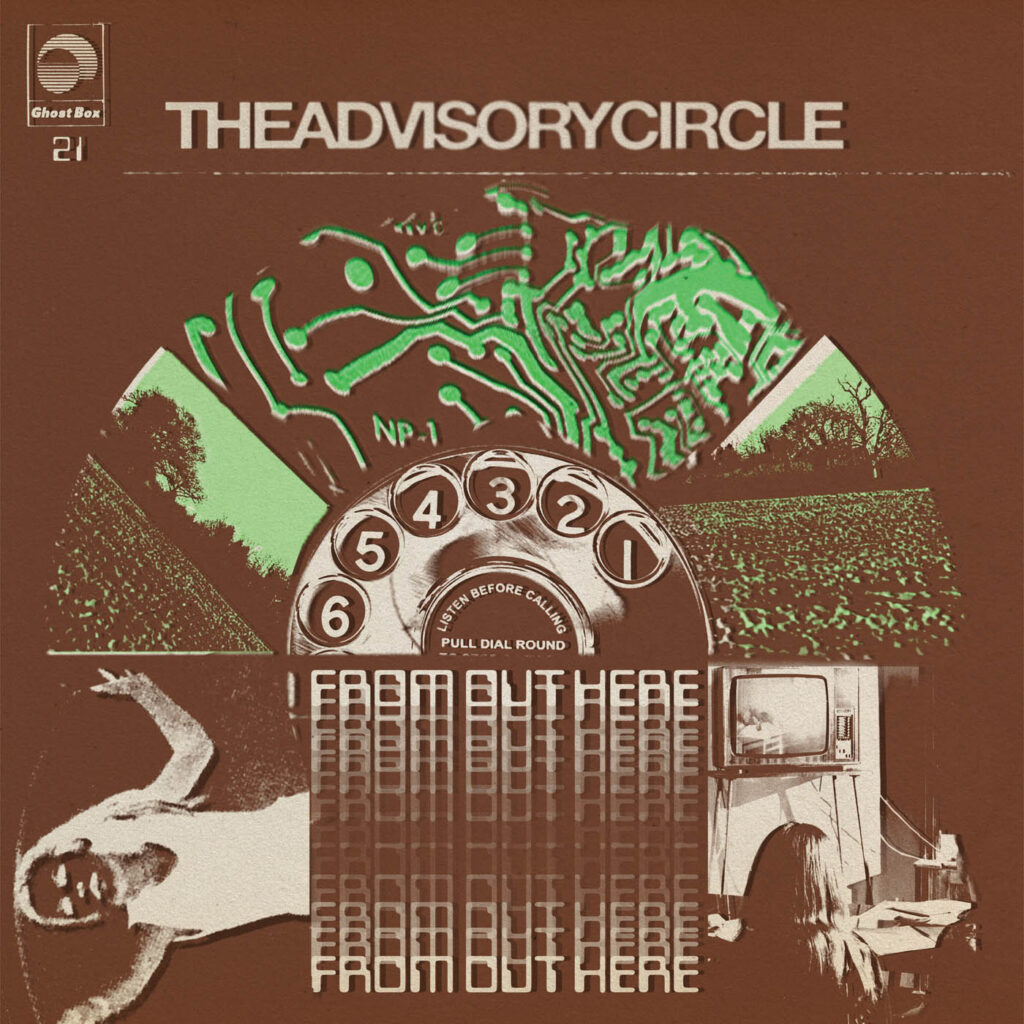

Ghost Box have a number of regular contributors and one of the most important of these is Jon Brooks, who records as The Advisory Circle and seems to have assumed the role of the label’s third wheel.

“Jon came to us really early on, when he was doing stuff for Lo Recordings as King Of Woolworths,” explains Jupp. “Someone at Lo mentioned Ghost Box to him and he immediately said to himself, ‘This is it! This is what I want to do’.”

Brooks has a background in music engineering and mastering, as well as being a composer and music producer, and he’s been integral to the development of the technical side of the label.

“Jon has done an enormous amount in helping me get my head around music production,” continues Jupp. “He does all our mastering work and if we do something new we always run it past him first. He’ll give us a critique on the technicals, on the way a track sounds, and if it needs improving he’ll know how to do it. So he’s become part of the collective.”

The word “collective” reinforces the feeling of something going on at Ghost Box that’s almost wilfully non-conformist. Some people talk about the label with a similar level of reverence to the way they used to talk about Factory – as a complete, idiosyncratically democratic identity.

“The label itself is more important than the individual artists,” explains Jupp. “The label is what means the most to people. We all work fairly anonymously and we only work with people who understand that. So if someone comes along who has a load of photos of themselves on their record sleeve or on their press releases, they’re not really going to fit in with us.”

Of course, Factory was never afraid to push the envelope in terms of releasing challenging and experimental material. The same is true of Ghost Box. Take Drew Mulholland’s recordings as Mount Vernon Arts Lab, for example.

In his day job at Glasgow University, Mulholland holds the grand sounding position of Composer in Residence and Research Fellow in both the Schools of Geographical & Earth Studies and Physics & Astronomy. He’s just completed two new works, one for the University’s First World War commemorations, which took place in September, and another for the School of Physics & Astronomy to celebrate the International Year of Light 2015. The latter was composed on a harp played by laser beams, with a score based on the alchemical writings of philosopher and occultist Cornelius Agrippa.

Mulholland is also putting the final touches to his next Mount Vernon Arts Lab album, ‘A Spectre Over Albion’, which follows last year’s ‘Norwood Variations’. Featuring string quartets, choirs, musique concrete and spoken word, the record is slated for an early 2016 release and sounds as intriguing as its predecessor.

“I’ve manipulated the sound of the Earth’s electromagnetic field, recorded with a VLF Receiver,” offers Mulholland. “I’ve also mixed in field recordings along with samples from some hypnotic regression therapy tapes I found in a charity shop.”

All of which sounds definitively hauntological and points to the mutual attraction between Mullholland and Ghost Box. Jupp and House have cited Mount Vernon Arts Lab’s ‘The Séance At Hobs Lane’ album from 2001 as an influence on them wanting to start a label in the first place. And during his Glasgow University lectures and seminars, Mulholland frequently references Julian House’s work and occasionally screens his films and project artwork.

“I love the Ghost Box aesthetic,” declares Mulholland. “I think the world that Jim and Julian have created is quite brilliant, but from my considered academic perspective I also believe Mr House to be the most talented and visionary graphic designer and film-maker we have in Britain today.”

For any record company to progress, it needs to evolve. And that’s what seems to be happening at Ghost Box right now, with acts like The Soundcarriers and Pye Corner Audio bringing something new to the “house” sound. The Soundcarriers in particular are not the sort of outfit you would instinctively associate with the label. Jim Jupp had been a fan for some time, but they contacted the label so no courting was required. They had their ‘Entropicalia’ album pretty much in the bag and simply asked Ghost Box if they wanted to release it.

“They’re a band in the traditional sense, but Julian and I talked about it and agreed they would be a great addition if we were able to package them up properly, so it didn’t feel like there was too much of a ‘gap’ as it were,” says Jupp. “They might’ve wanted an album that sold them as a live act, as a glamorous four-piece, but they weren’t interested in any of that. We were able to make this work on the visual side and we wanted to push the label on a bit musically, so it was the ideal scenario.”

We’re envisaging a similar scenario with Pye Corner Audio, who sound very much at home on Ghost Box now.

“We were aware of what Martin Jenkins was doing as Pye Corner Audio and really liked it,” says Jupp. “He approached us with his first demo, which we turned down, but then I got friendly with Martin and slowly built a dialogue. He’d also got to know Jon Brooks, which helped. When he presented the demo for the album that eventually became ‘Sleep Games’ we thought, ‘Yeah, this haunted dancefloor sound is something different and could definitely work’. We started thinking around this idea of a boarded-up nightclub in Belbury, resonating with the echoes of the old raves that had taken place there, and then it made sense to us.”

Ten years down the line, the Ghost Box visionaries are clearly as sharp and in control as ever. So what’s up their sleeve next?

“Looking to the longer term future I’d like to see us getting involved more in the world of soundtracks,” answers Jupp. “In many ways, that’s how we started, with this love of library music that had a certain utilitarian aspect. But I’d also like to work with more acoustic artists too, especially singer-songwriters.”

For now, though, the expansion tool for the label comes in the form of a series of seven-inch singles called ‘Other Voices’. It really is a brilliantly realised departure.

“The ‘Other Voices’ releases are opportunities for us to work with people who might have approached us or people we’re fans of, but whose work wouldn’t necessarily makes sense as a Ghost Box album,” explains Jupp. “The next one in the pipeline will be with Tim Gane from Stereolab, who Julian has known for years because he worked on most of Stereolab’s record covers and promo videos. Tim’s just finished a couple of tracks, which we’re just putting in the sausage machine for a release very soon.”

The single will appear under Gane’s Cavern Of Anti-Matter guise and Jupp lets slip that Gane is also just putting the finishing touches to a new album. During the recording sessions, he had it in mind that a couple of the tracks would come out through Ghost Box.

“They’ll essentially be spin-offs from his album but they’ll be on the album too, which is a really nice touch,” says Jupp.

“It makes me think how lucky we are to have got where we have… I never would’ve expected all this 10 years ago. I heard someone the other day saying it’s such a terrible time to be in the music industry, but to me it’s also a golden age. The opportunities are fantastic, even though the rewards are tiny. And if you can find your own path, you can just about make it work.”