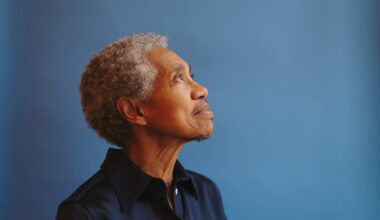

With a comprehensive boxset just released, Heaven 17’s Glenn Gregory and Martyn Ware tell us how their unmistakable electro-soul sound came into being – and why they’re finally mastering the art of playing live.

Fired up by vengeful rivalry and steely ambition, Heaven 17 were more than ready for the big time when they first formed in Sheffield almost 40 years ago. Just hours after their shock exit from The Human League, Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh recruited old friend Glenn Gregory and drew up a new musical manifesto almost overnight: big pop hits grounded in electro futurism, African-American funk and stroppy Yorkshire attitude.

“We had absolutely no fear,” says Gregory. “We were just three young lads from Sheffield who were going to take over the world.”

“Sheffield has always had a bit of a maverick attitude,” says Ware. ”It’s the natural bolshiness of the People’s Republic Of South Yorkshire. It’s a place where people do stuff rather than consume stuff. There’s still an enormous scene up there, and it mostly doesn’t sound like

anywhere else.”

Now slimmed down to the core duo of Ware and Gregory, Heaven 17 have spent the last year rummaging through their archives for a deluxe boxset, ‘Play To Win: The Virgin Years’. Spanning the band’s imperial phase from 1980 to 1988, this lavish anthology spreads a banquet of albums, singles, B-sides, remixes and rare deep cuts across a generous 10 discs, all handsomely packaged with a 36-page booklet and sleeve notes.

“We’ve always treated our work as a kind of extended art project,” laughs Ware. “It’s not just about creating a legacy and putting it to bed, it’s about fleshing out the context and condensing it into one thing.”

For fans of Heaven 17’s post-punk avant-synth roots, the most interesting material in the collection will be the bonus disc of demos dating back to 1980: glitchy, loopy, bleepy doodles that would have sounded comfortably at home on Sheffield’s pioneering techno label Warp a decade or so later.

“We’ve always done this thing of writing fragments,” says Ware, “little experiments to see if we could get an interesting groove going, then seeing what those grooves would engender in terms of concept or lyric or whatever. We have a low attrition rate for developing backing tracks that don’t get made into songs, because basically we think everything we do is brilliant. Ha! Only joking, not brilliant, we think it’s adequate. But there have always been snippets that don’t end up coalescing into something bigger, and that’s what those things are.”

One of the most curious inclusions among the demo tracks is a prototype of Heaven 17’s biggest hit, ‘Temptation’, set to a lascivious electro-glam beat that sounds uncannily like Soft Cell’s immortal version of ‘Tainted Love’ – and may even predate Soft Cell, if the disc chronology is accurate. Ware and Gregory seem unaware of the parallels.

“It’s more Marc Bolan really, or Gary Glitter, that kind of swing,” says Gregory. “We probably got it from The Glitter Band. That whole glam thing was big for us. We were just messing around, trying to find beats. It’s all down to the equipment mainly, those early drum machines. And then when Martyn decided on the Motown backbeat idea, it changed the song for the better. It had more individuality, not so electronic.”

Long before Heaven 17 were born, Ware, Marsh and Gregory spent their teens in a variety of Dadaist electro-punk bands with names such as Musical Vomit, Dead Daughters and VDK & The Studs. Most of these short-lived collectives were born from the feverish creative hothouse of Meatwhistle, an experimental theatre and art project in the heart of the city.

Founded in 1974 by actors and drama teachers Chris and Veronica Wilkinson, this council-funded venture was largely designed to give working-class children access to the arts.

“Without Meatwhistle, The Human League and Heaven 17 would not have existed, categorically,” says Gregory.

Former computer programmers who recognised the dawning pop potential of primitive analogue synthesisers before most of their peers, Ware and Marsh became the musical driving force behind The Human League. Indeed, Gregory might well have become the band’s singer if he had not left Sheffield for London at the age of 17 to work as a photographer. Instead, Ware called on his old schoolfriend Philip Oakey to front the band, more on the strength of his striking haircut than his vocal prowess.

But in October 1980, after releasing two critically revered albums, The Human League dramatically ditched Ware and Marsh on the eve of a tour. According to Ware, official claims that he and Marsh walked out over internal tensions with Oakey are a “mythical narrative that’s been propagated for years”.

In reality, he says, band manager Bob Last and Virgin Records engineered the split because they planned to transform the League from cult outsiders to profitable pop stars with their next album, which became the hit-packed synthpop masterpiece ‘Dare’. Meanwhile, the label also banked on retaining Ware and Marsh as a spin-off musical unit and studio production team. It was, Ware snorts, a “two bands for the price of one” deal.

“This only came out later, but Bob Last and the record company had been plotting it for months,” says Ware. “You’ve got to bear in mind that Bob – who I still really like by the way, it’s not a bitter and twisted thing – was a disciple of Malcolm McLaren. He loved this kind of Machiavellian stuff. Anyway, the upshot is it worked out fine. To be honest, even if we had done the third album together, that wouldn’t have been ‘Dare’ or anything like it. So the shit would have probably hit the fan before the fourth album anyway.”

By fateful coincidence, Gregory was back in Sheffield on the very day the League split. He was home on assignment to photograph a Joe Jackson concert at the City Hall, but instead he met up with a seething Ware at the nearby Red Lion pub.

“Martyn had been thrown out of his own band,” says Gregory. “He was obviously a bit irate, so we just had lots of pints. And by the end of that night, as we left the pub, we’d arranged that I would come back to Sheffield and we’d form a new band. That was a Friday night, and I was back in Sheffield on Monday – we went straight into the studio.”

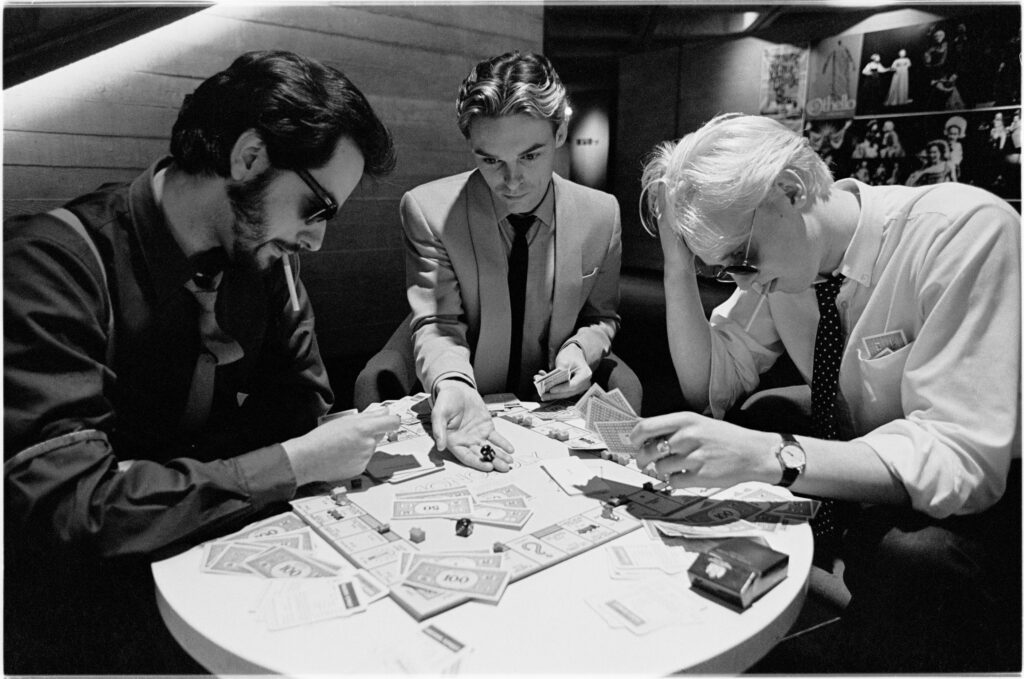

One of the strangest aspects of the split is that The Human League and the embryonic Heaven 17 still shared a studio, in West Bar on the northern edge of the city centre. The two rival bands found themselves using the same space and same basic eight-track equipment on a round-the-clock rota, like a newly divorced couple juggling child custody.

“Calling it a studio is really stretching the imagination” Gregory laughs. “It was a derelict vet’s building. The vocal booth was the kitchen, which had 10,000 rotting milk bottles in it. The Human League were working 10 in the morning until 10 at night, and we were working 10 at night until 10 in the morning. It was proper shift work. But those two albums, ‘Dare’ and ‘Penthouse And Pavement’, came out of that turmoil. It was an incredibly creative time.”

Regardless of any lingering bad blood, Heaven 17 remained inextricably linked to The Human League in these early days. They even went to see the reconstituted League, featuring newly recruited teenage vocalists Susan Ann Sulley and Joanne Catherall, when they played the Rotters club in Doncaster just a month after the split. Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.

“I’m not a bitter person,” says Ware, “I converted the sense of betrayal into creative energy. It wasn’t a revenge thing, it was a kind of, ‘We’ll show them’. There was a real arms race to see who could get the first single out, the first album, who could have the first hit, who would rise quickest out of the ashes.”

From the start, Heaven 17 injected American soul elements and politically charged lyrics into their very British sci-fi synthpop sound. Having grown up listening to northern soul, funk and disco, with two older sisters who loved Motown, Ware ambitiously modelled his new band’s quasi-corporate image on Parliament-Funkadelic and The Chic Organization. “Cameo without the codpieces”, as they once jokingly described themselves.

“That must have been Martyn, because I would have quite liked the codpieces,” says Gregory.

Heaven 17’s electro-soul sound came into focus very quickly during their first week of recording together. Midway through making the synth-heavy ‘(We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang’, which would become their debut single and signature song, they decided the track needed a funky bass guitar solo. “But who the fuck plays funky bass in Sheffield?” laughs Gregory.

As luck would have it, Gregory had taken a job at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre, where one of his fellow stage hands, John Wilson, turned out to be a self-taught bass virtuoso.

“This little quiet black guy,” the singer says. “He didn’t even take his coat off, I remember it completely. It must have been strange to him because he played music in church, but his chops were fantastic. We didn’t know, but he had just bought himself that bass in a secondhand shop. And it was a right-hand bass and he was left-handed, so he was playing it upside down!”

When Wilson informed Heaven 17 that his first instrument was actually a guitar, Gregory took him home in a taxi to collect it. Their debut album, ‘Penthouse And Pavement’, suddenly became an electro-funk pop-soul hybrid.

“Fate threw John Wilson in our direction, who just transformed what we were doing completely,” says Ware.

With its painted sleeve depicting the band members as pony-tailed corporate executives, ‘Penthouse And Pavement’ effectively predicted the dawning Thatcherite era of yuppie pop.

“It was to open everyone’s eyes to the idea that the record company was a business, not a hippie love-in,” says Gregory. “We were taking the Mickey. Unfortunately, some people took us seriously.”

“The ironic thing is, I don’t think any of our families in Sheffield even knew anybody who had a business,” laughs Ware. “We all came from working class families, and we were kind of fantasising about what it might be like. We invented this world where we were this multinational company, just as a kind of ironic art project.”

But there was little irony in lyrics like ‘Soul Warfare’ and ‘Let’s All Make A Bomb’, deceptively upbeat commentaries on economic inequality and Cold War militarism in the Thatcher/Reagan era. All sons of steel workers and shop stewards, Heaven 17 were sharp-suited socialists at heart.

“It wasn’t a fashion thing, it was absolutely ingrained within us,” says Gregory. “I’ve probably become a middle class London media ponce now, but I still have aspirations to be a working class Sheffield socialist. And I must say where we are today in the world is pretty much exactly where we were when writing ‘Fascist Groove Thang’.”

Released in September 1981, ‘Penthouse And Pavement’ became a Top 20 hit, establishing Heaven 17 as left-field pop stars. Around the same time, the trio relocated from Sheffield to London. Gregory returned to his tiny flat in Ladbroke Grove, west London, which had long been the “unofficial South Yorkshire Embassy” for touring bands in the early Human League days. Ware and Marsh soon followed, finding their own places nearby, conveniently within walking distance of Virgin Records’ HQ.

For their next project, Ware and Marsh worked under the British Electric Foundation banner to produce their first full album, ‘Music Of Quality And Distinction Volume 1’, a cover version collection featuring vocals from Sandie Shaw, Paul Jones, Paula Yates, Billy MacKenzie

and others.

“‘Music Of Quality And Distinction Volume 1’ was like a manifesto for electro-soul production,” says Ware.

David Bowie and Frank Sinatra turned BEF down, but funk legend James Brown initially agreed to record a version of the Temptations classic ‘Ball Of Confusion’. Alas, the Godfather Of Soul then demanded an impossibly high royalty deal, so the BEF team approached Tina Turner instead, opening the door to a fruitful studio partnership that would kick-start the R&B queen’s blockbuster comeback. Gregory has some colourful memories of this starry period, including MacKenzie dancing around a studio “stark bollock naked” in front of bemused Virgin bosses.

As they geared up for their second album, Heaven 17 were becoming proper pop stars with grandiose ambitions to match, working with a full orchestra in a prestige multi-track studio. Released in April 1983, ‘The Luxury Gap’ became a platinum-selling smash, peaking at Number Four in the UK. It also spawned a run of hit singles, notably the roaringly orgasmic soul-pop anthem ‘Temptation’ and the gospel-fired romantic ballad ‘Come Live With Me’.

But even in their unassailable prime, Gregory insists Heaven 17 never became flashy playboy pop stars. Well, maybe just a little.

“We obviously had a decade on drugs, but who didn’t?,” the singer grins. “That was just what was going on. But not to excess, really. No Ferraris. Having said that, my first car after passing my driving test did happen to be a Jensen Interceptor, which had that big V8 engine and was always breaking down. I’d be driving down the King’s Road, and it was like being in a sauna. I had to drive in my underpants, it was so hot. Ridiculous.”

Commercial success brought its own pressures for Heaven 17. The trio’s dogmatic principle of not playing live began to backfire on them when the hits, and the potential rewards for touring, got bigger and bigger.

“At that time MTV had just started,” says Gregory, “and it looked like a much more modern way of getting in touch with people and selling your music that way. It just seemed very rock ’n’ roll and retro to play live, very 70s. We viewed ourselves as modernists and forward-looking artists, so we said, ‘Let’s not play live’.”

“We thought it was futuristic, more enigmatic, “ says Ware. “We thought, ‘If they can’t have us, that makes us more attractive somehow’. But it was a double-edged sword when it came to ‘The Luxury Gap’ and we started having big international hits. For instance, we were offered a million pounds to do five dates in California, sponsored by Coors beer. And we turned it down, because we didn’t want to become a touring band… which is phenomenally stupid in retrospect.”

Perhaps because of their reluctance to play live, Heaven 17’s commercial golden age was brief. After ‘The Luxury Gap’, their sound became smoother, and their chart success began to slide. In 1988, Virgin dropped them following their fifth album, ‘Teddy Bear, Duke & Psycho’. The band went into hibernation for much of the following decade, as all three members worked on other projects. But Heaven 17 enjoyed something of a comeback in the 90s, playing their first-ever live dates in 1997 when Erasure invited them out on tour. Since then they have toured with increasing regularity, to ever larger crowds.

As the 21st century dawned, Heaven 17 patched up any lingering ill feeling with The Human League after appearing on screen together in Eve Wood’s 2001 BBC documentary, ‘Made In Sheffield’. The bands are now on friendly terms, even playing live together on the Steel City tour in 2008.

“It took about 20 years,” says Ware. “We got back together and realised how much we loved each other during this very formative part of our lives. I’m not one for holding grudges anyway, we’ve all been through a lot of stuff since then.”

In 2007, Heaven 17 suffered a rupture of their own when Marsh quit without warning, cutting off all ties with his former bandmates. He reportedly went to university and then became a teacher in Sheffield, but Ware and Gregory remain confused by his abrupt departure more than a decade later.

“He literally just stopped talking to us one day, it was really weird,” Ware shrugs. “We’ve heard via various third parties how he’s doing, but he’s never actually talked to us since then.”

Gregory seems equally baffled.

“Honestly there was no bad feeling, no darkness, no arguments,” he says. “He just pulled away and did something else.”

Far from being semi-retired pop stars in 2019, Ware and Gregory both have multiple ventures keeping them busy. Working with Heaven 17’s long-time keyboard player Berenice Scott in their Afterhere band and soundtrack project, Gregory writes film and TV scores. The duo released their debut album, ‘Addict’, last year. Gregory is also frontman with Holy Holy, the glam-era David Bowie tribute supergroup led by Woody Woodmansey and Tony Visconti, which plays sell-out tours in Britain and abroad.

Meanwhile, Ware is a visiting professor at Queen Mary University of London and principal tutor of several post-grad courses at the educational wing of Tileyard studios in north London. He also travels all around the world working on 3D soundscapes and sonic installations with Illustrious, the company he co-founded with Vince Clarke in 2001.

Consequently, Heaven 17 have become so booked up with other commitments they have yet to finish their latest work-in-progress album. But the seven tracks recorded so far, released as a taster EP in 2016, indicate a promising return to the raw monophonic sound of their early avant-synth days. They have even dusted off the antique Roland System 100 machine that Ware and Marsh used to compose the debut Human League single ‘Being Boiled’.

“That big fat analogue sound, with such depth and width,” says Gregory. “That’s what we’re doing in the studio now, with an idea to be more electronic.”

“It’s not a nostalgia thing,” says Ware. “I just think there’s a lot of value in that kind of sound palette. We could make contemporary sounding EDM records, no problem. We could do it under an alias for other people if we wanted. But I don’t particularly like it, I think it’s a bit dull. We could also do edgy experimental electronic music, but would that make me happy?”

In the meantime, Heaven 17 are now a regular touring band. In just the last decade, they played both ‘Penthouse And Pavement’ and ‘The Luxury Gap’ in full for the first time ever.

“We did over 50 gigs last year and we’re doing a similar amount this year,” says Ware. “We have a young female band, and we try to make it as relevant and contemporary as we can.”

“Heaven 17 has become a totally enjoyable sideline,” Gregory laughs. “We absolutely love playing live now, and I think we’re getting quite good at it. We’ve just about mastered it.”

‘Play to Win: The Virgin Years’ is out on Edsel/Demon

While we have you, why not take a minute to browse our online shop?

We’ve got print magazines, limited edition vinyl, must-have books, CD boxsets, and we ship worldwide. Click below to open a new tab and keep your current reading place.