He is the godfather of disco and so much more. We talk Munich, his Musicland Studios, The Rolling Stones, Queen and Led Zeppelin. Temperamental Moogs, Kraftwerk and Donna Summer. David Bowie and Oscar-winning soundtracks. Daft Punk, Space in Ibiza and being a globe-trotting superstar DJ aged 76… It’s time to Say hello to the irrepressible Giorgio Moroder

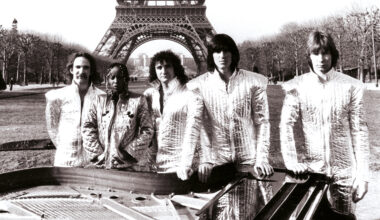

Most people couldn’t pull off launching a new career as a superstar DJ after turning 70, but then most people aren’t Giorgio Moroder. The Italian-born disco king spent most of his half-century musical journey on fast-forward to the future, pioneering the use of analogue synthesisers in pop, dabbling in experimental electronica, releasing the first extended remix and making the first all-digital album. Moroder’s immortal Eurodisco anthems secured his place in the pantheon of dance music legends, as Daft Punk confirmed by making him the star guest on their hugely successful 2013 album, ‘Random Access Memories’.

Only in the last few years has Moroder come out semi-retirement to claim his rightful throne as the daddy of the DJ booth. The ace of basslines has become the king of clubs once more. And now the 76-year-old disco godfather has compiled his first-ever DJ mix for Space, part of the legendary Ibiza club’s stellar swansong package of farewell releases. As we might expect, his track selection leans heavily on his own vintage classics and 1970s contemporaries, but with a sprinkling of more recent artists like Tensnake and Joris Voorn too. Even at 76, Moroder still has one ear on the musical future.

“We thought the real disco sound would be the best way to celebrate Space,” Moroder explains. “So I have some of my songs, some by Cerrone, all songs that represent quite well the years 1976-78 . For home listening I would probably have only picked my songs, ha!, but for a club it’s better to have a bit of variation.

“I think the songs represent what people were listening to at the time. I don’t really know Tensake that well, but he’s certainly hip right now. We thought he’d fit perfectly, give a little more variety to the whole collection.”

Nightclubs have long been Moroder’s natural habitat, but he was not always the disco king. His earliest club performances were as a singer, not a DJ. His short-lived career as a hirsute pop crooner began in the late 1960s when he was living in Berlin. After a few minor hits, he moved into songwriting and production, relocating to Munich in 1970. Looking back, he sees few parallels between modern clubs like Space and the provincial German dance palaces of his youth.

“There were no discotheques in the same sense as now,” he recalls. “DJs would just play one song, and then the next song. It is so different from what good DJs do now. It’s almost impossible to compare them. The technology, the way they segue songs without changing speed, or maybe changing it in a way the audience doesn’t even notice. I remember, around 1969, I was doing a little bit of DJing, but it was mainly singing to tapes. Sometimes I would take some 45s with me or I had mixes on tape, but I wouldn’t call that DJing.”

In Munich, Moroder set up his own Oasis record label and built the fabled Musicland recording studio in the basement of the futuristic Arabella-Hochhaus complex in the east of the city. His apartment was in the same high-rise development, so he commuted to work by elevator.

“I liked Munich because it’s only about three hours from my home in Italy,” Moroder explains. “Musicland was great, but there were times when I couldn’t use it because I had The Rolling Stones there, and Queen, and Led Zeppelin made ‘Presence’ there. It was good, you could experiment because it’s not expensive if you have you own studio, but a lot of times I had to go to a different studio because once Mick Jagger has called and asked if he could have the studio, you couldn’t say no because he would never have come back.”

It was at Musicland that Moroder first developed his fascination with electronic instruments. Hearing the Wendy Carlos album ‘Switched-On Bach’, the seminal synthesiser landmark released in 1968, was something of a eureka moment. He immediately began seeking out Moog synths, which were extremely rare and expensive in the early 1970s. By happy coincidence, a studio engineer called Robbie Wedel introduced him to Eberhard Schöner, a Munich-based classical composer who owned one of the first modular Moogs in Europe, which he used chiefly for avant-garde soundscape pieces.

Schöner guarded his Moog jealously, but when he was busy elsewhere, Moroder and Wedel began hijacking it for their own groundbreaking early synthpop experiments. One of the first compostions was Moroder’s 1971 novelty single ‘Son of My Father’, released under the name Giorgio, which British band Chicory Tip covered and had a chart-topping hit with a year later. Moroder found the early Moog an exasperating, unwieldy beast.

“Without this guy, Robbie Wedel, I would never have been able to use it,” he admits. “First of all, at the time it cost about $100,000, and it would have taken me at least six months on a daily basis to find the sounds. And then the tuning. I was able to play it for maybe 10 or 15 seconds, then re-tune, then do another 15 seconds… it was absolutely, incredibly difficult.”

While Moroder persisted with trying to bring analogue synthesiser sounds into commercial pop, he also dabbled in leftfield electronica, most notably on his 1975 solo album ‘Einzelgänger’. With its pulsating rhythms, mechanised beats and robotic vocoder chants, this underrated milestone almost feels like a road map for Kraftwerk’s embryonic career. But Moroder felt no musical kinship with the deadpan Düsseldorf boffins.

“I liked the fact that a German group was successful, especially in America,” he nods. “There was nothing similar coming from Germany. I loved the sounds, but not really the music in itself. We didn’t really have that much contact. They were in Düsseldorf, I was in Munich, and then I left for America. I think I met them once or twice.”

Moroder’s electric dreams finally became reality thanks to the perfect storm unleashed by the disco boom, a fateful meeting with a legendary diva, and a cocaine-fuelled orgy. Forging a new partnership with British lyricist and co-producer Pete Bellotte, who had co-written ‘Son Of My Father’, Moroder began writing songs for Donna Summer, an American gospel singer who had settled in Munich after appearing in a touring German production of the hippie musical ‘Hair’.

The trio’s breakthrough came with ‘Love To Love You Baby’ in 1975, a seductive disco-funk workout featuring a primitive drum machine and some seriously orgasmic vocals. Moroder later extended the original European edit into a 17-minute remix at the request of Casablanca Records boss Neil Bogart, who called from the middle of a druggy sex party suggesting the song should be long enough to fill one whole side of a vinyl album.

Initially reluctant, Summer re-recorded her ecstatic vocal moans lying on the floor of a darkened studio. The song became a worldwide smash, hitting Number Four in the UK and Number Two on the Billboard charts.

Moroder’s fruitful chemistry with Summer and Bellotte hit new heights on their landmark 1977 electro-disco anthem ‘I Feel Love’, a space-age whoosh of propulsive synthetic basslines and vaulting vocal acrobatics. Brian Eno famously told David Bowie that this groundbreaking all-electronic production was the sound of the future, and he was not wrong. Innumerable hi-NRG disco, house and techno producers have since tried to replicate its libidinous cyborg groove.

Moroder and Summer later worked together on a run of huge singles including ‘Bad Girls’, ‘Hot Stuff’, ‘On The Radio’ and many more. But as the hits dried up, the disco king lost touch with his most famous collaborator.

“I was never mad at her,” Moroder insists. “The thing is, I think she made a big mistake, she sued Casablanca and then she went with Geffen, and that was not a great wedding. I did a double album with her that was never released. But we never had a fall-out at all.”

Although Moroder found fame during the ultra-hedonistic Studio 54 years, Bellotte has claimed he and his studio partner never indulged in drink and drugs. With hindsight, Moroder shrugs off his cartoon reputation as a porn-stached disco playboy presiding over Munich’s bacchanalian party scene.

“There’s an image,” he laughs. “There was hedonistic stuff later when Freddie Mercury came in, and he was there for months. He was the king, or the queen, of the nightlife in Munich. Freddie did a lot for that image. What Eno and Bowie did for Berlin, Freddie did for Munich.”

Revisionist pop historians tend to concentrate on Moroder’s imperial Eurodisco phase, politely glossing over his 1980s move into power ballads and anodyne movie soundtracks. But the disco king seems proud of all his work, even the uncool chapters.

In 1978, his career entered a new phase with his synth-heavy score for Alan Parker’s prison-break thriller ‘Midnight Express’. It won him the first of three Oscars and a flood of Hollywood offers. Relocating to LA, he began a prolific run of soundtracks including ‘American Gigolo’, ‘Scarface’ and ‘Cat People’. Two further Oscars followed for co-writing the smash hit theme songs, Irene Cara’s ‘Flashdance… What A Feeling’ and Berlin’s ‘Take My Breath Away’ from ‘Top Gun’.

“To produce a pop act, that is great, but doing a movie is a little bit higher in terms of creativity,” Moroder says. “I think the creativity of directors and screenwriters is quite high, so to work with those people gives you more satisfaction. Plus you don’t just do a song, the song has to fit the movie, so the challenge is more but the reward is greater too. You go to see the movie and you see people applauding when your name comes up on the credits.”

And then you win three Oscars.

“Absolutely! That’s on the side, ha!”

Moroder’s film work brought fresh collaborations with A-list stars including Blondie, Freddie Mercury and David Bowie. In 1981, he and Bowie co-wrote ‘Cat People (Putting Out Fire)’, the title song for Paul Schrader’s 1982 erotic thriller ‘Cat People’, which Bowie later re-reworked for his ‘Let’s Dance’ album.

“The professionalism with Bowie was incredible,” Moroder recalls. “I sent him the tapes, he liked the demo, so we met in Montreaux for dinner and talked about the song. He said, ‘OK, let’s start tomorrow’. I thought we would probably start at 1.30 or 2pm, but he said, ‘I come for breakfast at nine and then we go to record’. And that’s it. I think we started at 10 or 10.30 in the morning and did about two or three takes. He was fantastic.”

But Moroder was not so lucky with his most ambitious movie project. In 1984, he released his GM-modified remix of Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent sci-fi classic ‘Metropolis’, which he colourised and slathered in a mullet-haired electro-rock soundtrack featuring Freddie Mercury, Pat Benatar, Adam Ant, Bonnie Tyler and others. The film was a modest hit, but critics declared it an act of cultural vandalism, singling out the music for special derision.

“That was a difficult thing,” Moroder sighs. “At the beginning I didn’t really know, should it be pop, should it be rock? So I did a test with an audience and it turned out they wanted more rock stuff, which wasn’t my best side. Also I was so involved with the movie itself, cutting and trying to find new pieces and all that stuff. So the music was recorded, but then the film took two years to come out. By the time it came out the songs were already dated. But you can’t go back to Freddie Mercury and say, ‘OK, let’s do another song’.”

Moroder’s 1980s productions included albums with Sparks, Nina Hagen and The Human League’s Phil Oakey.

In 1985, he also worked on ‘Flaunt It’, the debut album by cyberpunk peacocks Sigue Sigue Sputnik. The garish electro-glam pranksters were widely regarded as a trashy novelty, but they scored a major hit in early 1986 with their first single, ‘Love Missile F1-11’. Three decades later, he is still refreshingly upbeat about the Sputniks.

“I loved them!” Moroder beams. “Those guys were characters. They were not the greatest musicians or the greatest singers, but they were good fun. I really liked the idea to insert sounds from movies in songs, which I thought was brilliant. I loved them, especially the first single, ‘Missile Number 1’ or whatever. The album was little more difficult because of their limited composing skills. But all in all, really great guys.”

By the late 1980s, Moroder was already “half-retired” from the pop world. He began to diversify his interests, writing Olympic theme tunes, dabbling in film and visual art. At the dawn of the 1990s, he married his American wife Francisca and began working on the Cizeta-Moroder, a bespoke Italian sports car with an eye-watering price tag. The project ended in acrimony and fewer than 20 cars were built. After one last solo album, ‘Forever Dancing’ in 1992, he dropped off the musical map for two decades. Why the long hiatus?

“Ooh, I don’t know,” Moroder sighs. “The neighbour’s green grass is always more green. I did a movie made of photos that won an award at Palm Springs film festival. I started to play golf, ha! The music became less and less interesting… and then time passed. And then, they rescued me! Daft Punk.”

Thanks to his guest slot on ‘Random Access Memories’, Moroder credits the French disco duo with his current career resurgence. He was in Paris when the call came through from Thomas Bangalter and Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo to join them in their studio. Initially expecting to compose music together, he was surprised when they sat him down and asked him to reminisce for three hours.

But the finished track, ‘Giorgio By Moroder’, is an inspired, retro-favoured, nine-minute tribute to the electro godfather. Moroder has since half-jokingly suggested to Daft Punk that they release the full three-hour recording. He’s also keen to work with the duo again.

“I hope so,” Moroder nods. “If they call me like they called me last time, I’m ready.”

The Daft Punk connection certainly boosted Moroder’s profile, attracting a flood of new recording offers. Last year he released his first new album in over 20 years, the all-star electro-disco collection ‘Deja Vu’, which featured Kylie Monogue, Britney Spears, Charli XCX and more.

But in truth, Moroder’s current comeback began gathering momentum before ‘Random Access Memories’. In 2012, a friend at Louis Vuitton invited him to do a short DJ set for one of their Paris fashion shows. Soon afterwards, Elton John booked him to man the decks at a charity gala in Cannes. Both were short sets from an uncertain amateur.

“It was OK, I didn’t really like it that much,” Moroder shrugs. “But then the big offer came through, from Red Bull Music Academy in New York and that one, I loved it!”

Moroder virtually purrs with delight as he recalls his first proper club DJ set, an eye-opening epiphany in front of a rapturous crowd at Output in Brooklyn in 2013. The children of disco, house and techno came in their hundreds to pay homage to their founding father.

“It was absolutely fantastic,” he gushes. “A good DJ gets called back again, and I was really surprised that they got me back a few years later, and the audience had the same enthusiasm. The first time was a novelty, but the second time was as good as the first.”

Initially daunted by modern DJ technology, Moroder has now mastered the multi-channel Ableton Live software, allowing him more spontaneity on the night. “It has a little more life, a little more creative,” he says, “because each set is a little different.” From hesitant beginnings, he now has two DJ agencies booking him around the world. Last year he notched up around 40 dates, playing to crowds of up to 30,000 at festivals in Mexico City, Mumbai and Buenos Aires. All these late nights, loud venues and long journeys may seem an odd way to spend your autumn years, but Moroder disagrees.

“There are two motives,” he explains. “One: I always wanted to be a performer, but I never made it because my voice was not good enough, and I couldn’t remember lyrics. I was always in the back as a producer/ composer so when I got the chance, especially after New York, I thought, ‘Wow! This is great! Now I’m the artist!’.

“And the second thing, the money’s great! I make more money now than I did in my good days. And apart from that I travel the world, to cities where I would never go. With DJing, I went to 40 different cities last year. They pay the hotel, and they pay business class, which today in the great airlines is like first class. And it’s basically little more than an hour of work!”

Half a century after he first began making music, Giorgio Moroder has come full circle. From king of clubs to ace of basslines, from disco playboy to electro emperor. And now, he is back in clubland as the oldest superstar DJ on the circuit.

In a poignant piece of symmetry, Moroder’s glorious career resurgence coincided with Donna Summer’s untimely death from lung cancer in 2012. In her final years, the duo rekindled their friendship, not as musical collaborators but as neighbours in LA.

“We had a great time,” Moroder says warmly. “In her last few years I saw her almost more than when were working together. We moved into a beautiful apartment on Wilshire Boulevard and invited her for lunch, and she loved it, so she rented an apartment there too. We were on the fifth floor and she was just below me. Sometimes, she could hear me playing piano.”

‘Space Ibiza 1989-2016’, mixed by Giorgio Moroder, Erick Morillo and Mark Brown, is out on Cr2