As Kraftwerk visit the Uk for their most extensive tour since 1981, we trace the evolution of the Kraftwerk live experience – from dope smoke-filled hippy happenings IN the early 1970s to the sleek 3D art installations of the 21st century

“We were so much interested in different forms of everyday life, of art, of films, of literature, writing words, and like in the late 60s when the boundaries between different art forms were falling apart, so that opened for us the theme, too. We created our own words and combinations, creating a musical language and visuals, and that makes it so interesting rather than being a specialist in just one little category. That’s multimedia art.”

–Ralf Hütter

1969

The first verifiable gig that Ralf and Florian played was as part of the five-piece improv/psychedelic outfit Organisation. Throughout 1969, the group had a monthly residency at the Jazzkeller in Krefeld, a small city just outside Düsseldorf (and, coincidentally, Ralf’s birthplace), and released their one and only album, ‘Tone Float’, in August of that year.

According to drummer Alfred Mönicks, it was already’s Ralf’s show. He would hire and fire (the first victim was Peter Martini, a sax player), organise the gigs, and sort the contracts. He also held the purse strings, doling out 200DM (about £300 today) to each musician for making the Organisation album.

Organisation played a number of private shows, one for a bigwig of the Solingen knife company at his villa, by the swimming pool. “I received the highest salary I ever got from Kraftwerk – 600DM,” Mönicks recalled.

They performed at arts festivals too and even supported Frank Zappa & The Mothers Of Invention, but the group was going nowhere. After a year or so, Ralf and Florian’s first three musical assistants – bass player Butch Hauf, percussionist Basil Hammoudi and Mönicks – left them to it, at which point they became Kraftwerk.

You can see Organisation doing their thing on YouTube, captured in April 1970 at the second Essener Pop & Blues Festival. Ralf gets zero camera time and you can’t help wondering whether this was because, as far as his parents were concerned, he was supposed to be studying for his architecture qualifications rather than freaking out on TV with his pop group.

1970−1972

Before 1970 was over, the new Kraftwerk were playing around Düsseldorf and landing TV gigs, but the project remained a fluid and unfocussed affair for a few years yet. In 1971, Ralf even quit the band for a few months (to compete his degree), leaving Florian to hold the fort with a new three-piece line-up together with guitarist Michael Rother and drummer Klaus Dinger. It didn’t hold. Rother and Dinger went on to become Neu! and Ralf was reunited with Florian.

1973−1974

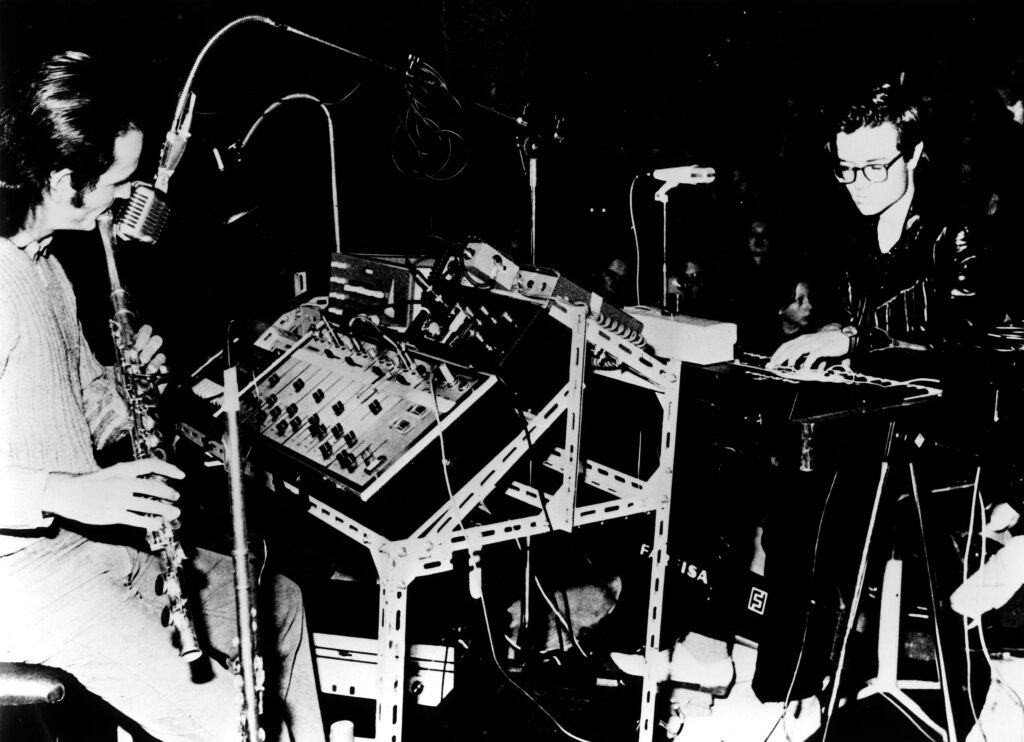

Kraftwerk’s synthesiser arsenal had been growing slowly but steadily through the protean early days. To begin with, processed organ and flute had been enough for their sonic ambitions, cleverly using tape delays to create the impression of multiple tracks of flute and to generate flowing waterfalls of melody from a simple keyboard line.

By 1973, they had added a Minimoog (played by Ralf) and an EMS AKS (mostly used as a signal processor by Florian), and had played their first shows outside Germany, with four dates in France, including one at the Bataclan in Paris. They’d also had their neon name signs made by this time, as you can see on the back cover of the ‘Ralf And Florian’ album. Their gear was housed in roughly put together bespoke stands and was all a bit Meccano, but Kraftwerk were not content to rely on off-the-shelf solutions for their stage needs.

By this point, they had enough knowledge of electronics to start making their own equipment too. When they were booked for a TV appearance in 1973, following the relative success of ‘Ralf And Florian’, they added Wolfgang Flür to the line-up to play their self-designed and self-built electronic percussion, replacing the rhythm machines they’d been relying on since Klaus Dinger’s departure.

The group played just three shows in 1974, at least one of them as a four-piece with Klaus Röder on violin. Check out ‘Kraftwerk – 1974 Frankfurt’ on YouTube for a lovely radio broadcast of one of them. Röder was considered a full member of the band for a while and was included on the artwork for the German edition of the ‘Autobahn’ album. But as 1975 got under way, he too was gone.

1975

The recording of ‘Autobahn’, released in November 1974, was the making of Kraftwerk as we know them now. Side two of the album is recognisable as an extension of what came before. ‘Autobahn’ itself, however, was a whole new proposition. This was the ultimate jaw-drop moment in electronic music history. Not a novelty record, not classics cranked out with trained virtuosity on a Moog, but a thorough, modern, artistic statement, replete with pop hooks, humour, and the kind of honed simplicity that comes from years of thought and experimentation.

The edit of the 22-minute title track was a hit in America and the UK, and so Kraftwerk made their first forays outside of mainland Europe with an extensive tour of the US in 1975. It was initially 22 dates, but more than double that number were added as word spread. This was followed by an 18-date tour of the UK in September, when OMD’s Andy McCluskey was among the small band of converts.

This curious period, which straddles the sudden and somewhat unexpected success of ‘Autobahn’, the hasty putting together of what became the “classic” line-up as Karl Bartos joined the band, and the recording and release of the ‘Radio-Activity’ album, included the appearance of the legendary “rhythm cage”. In what must have seemed like a great idea back in the controlled environs of Kling Klang, Wolfgang Flür designed a frame he could stand inside. Attached to the framework were photo-electric cells which would, theoretically, trigger drum sounds as he broke the beams with his hands. It didn’t really work, of course, leaving Wolfgang looking like a particularly suave policeman directing traffic. The rhythm cage was soon junked.

1976

Somewhat astonishingly, Kraftwerk didn’t tour either ‘Trans-Europe Express’ in 1977 or ‘The Man-Machine’ the following year. After their Roundhouse show in London on 10 October 1976 (tickets £1.90, support from National Health, Penguin Café Orchestra and DJ Andy Dunkley), they didn’t play live again until May 1981.

The Roundhouse show provided a glimpse of what Kraftwerk were up to, and where they were headed, with early versions of both ‘Trans-Europe Express’ and ‘Europe Endless’ given an outing. The break from live work gave Kraftwerk the time to record two masterpieces. Of these, ‘Trans-Europe Express’ was a hymn to the modern European ideal, steeped in pre-war nostalgia while name-checking David Bowie and Iggy Pop.

Kraftwerk ventured out of the studio for a photoshoot at Düsseldorf train station, which cast them as smartly dressed gentlemen travellers of leisure, but there were no gigs. They had developed a taste for the life of the reclusive genius.

1978

A change in image saw all four Kraftwerkers dressing the same: red shirts, black ties, black trousers. Their only public appearances in 1978 were carefully controlled television spots, plus two album “presentations” in April, one in Paris and the other in New York.

The stars of these promotional events were their new creations, their doppelgänger showroom dummies, who stood posing tirelessly for photographers in their high-waisted trousers, Dummy Florian holding a flute, Dummy Ralf with his hand resting camply on his hip, Dummy Karl behind a synth, and Dummy Wolfgang clutching his knitting needle drumsticks and electronic drum pad, like giant pre-gripping hands Action Men.

The press were lavishly boozed up and the idea that Kraftwerk actually were robots started to take hold. There was a single live date scheduled for late in the year, at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall in October 1978. Tickets were printed and sold, but the show was cancelled. One can only imagine the impact that gig would have had on the Manchester music scene of 1978.

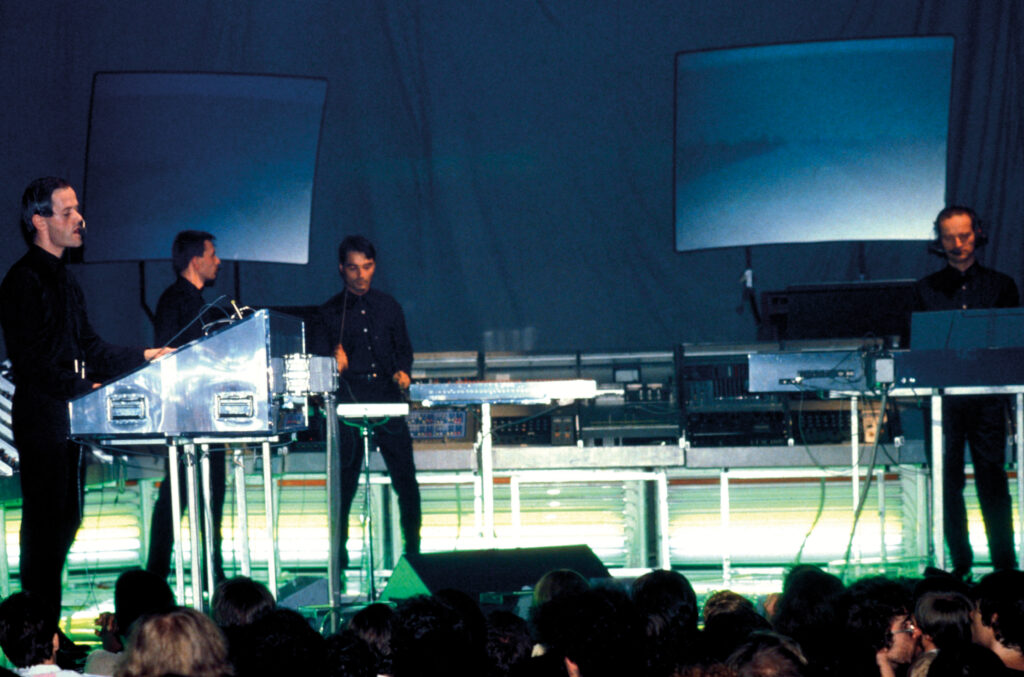

1981

After ‘The Man-Machine’, Kraftwerk slogged away in Kling Klang (if you call turning up to work in the evening and then going out for something to eat a “slog”), working on their prescient ‘Computer World’ album and making their studio portable. All that early fretting over building their own gear paid dividends when the curtain opened at the Apollo Theatre in Florence, Italy, on 5 May 1981, and the audience was treated to the spectacle of Kling Klang coming to life before their eyes. Neon tubes bathed the stage in a sci-fi glow as the four technicians strode purposefully to work and the powerful, speaker-filling beats of ‘Numbers’ thrilled the crowd. The studio was arranged in a V formation behind them in a series of consoles, one of which included the Kling Klang telephone. Whether it was used to order pizza during the 1981 shows remains unconfirmed.

1990–1998

The enormous 1981 world tour (nearly 100 shows) was clearly quite enough to be getting on with as far as Ralf and Florian were concerned. A UK tour was booked for 1983, but cancelled as it became clear that the album they were working towards (variously referred to as ‘Technicolor’ and ‘Techno Pop’) wasn’t going to happen, not least because Ralf was badly hurt in a serious bicycle accident.

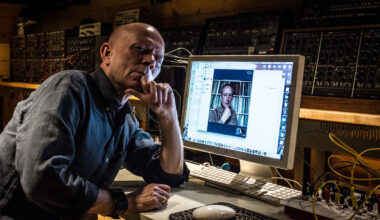

The rest of the 1980s were spent updating Kling Klang to a digital workflow and fussing over what became 1986’s ‘Electric Café’ album. Once that was on the tracks, they started on a back catalogue rejig collection, ‘The Mix’, which was released in 1991.

In 1987, exasperated by the lack of activity, Wolfgang Flür quit the band. Kraftwerk were not seen again until 1990, and even then it was just a secret four-date tour of Italy. Not even the record label were informed.

Wolfgang had been replaced by Fritz Hilpert and the Italian shows were the last that Karl Bartos played with the band.

In 1991, Kraftwerk took to the road again for 35 shows to promote ‘The Mix’ album, with Bartos substituted by the enthusiastic Portuguese musician Fernando Abrantes, who was soon ejected in favour of Henning Schmitz (the theory is that Abrantes pissed on his chips with a unacceptable display of sonic extravagance at the end of a concert at Sheffield’s City Hall).

There were a handful of gigs (23, to be precise) throughout the rest of the 1990s. These included three in 1992, one in Norwich and another in Leicester, both warm-ups for their Stop Sellafield bonanza with U2, while in 1997 they took their rightful place as the grandaddies of the dance music explosion by playing Tribal Gathering at Luton Hoo.

Ralf and Florian had visited the festival the previous year to check it out before agreeing to perform. The group had noticeably perked up the beats for the post-techno dance music scene and were now four in a row behind their workstations, but Kling Klang was still behind them. Tribal Gathering was to be their last UK show for seven years, but in 1998 the rest of the world got to see their now-familiar Tron suits for the first time, edged with the same UV reflective material as the band’s groovy sunglasses.

2006–2017

In November 2006, Florian lost the will to continue and played his last show in Spain. The 21st century had turned into a proper slog of world touring, and Florian had never been that keen. Wolfgang Flür remembers one night in Sydney in 1981 when Florian went AWOL before a gig. With minutes to go before stage time, he was spotted sitting in the audience. He wanted to see what the show looked like. “You don’t need me,” he said. When Kraftwerk took to the road again in 2008 for 15 dates around the world, Florian was absent, replaced by video technician Stefan Pfaffe. Florian’s departure from the band was finally announced in January 2009.

“Yes, he never likes touring, so in the last years he is working on other projects, technical things,” Ralf told the New Zealand Herald in 2008. The tour saw the band dressed in black and controlling the show from laptops. In a moment of high drama not normally associated with Kraftwerk, Fritz Hipert had a heart attack in Melbourne in November, just before the first of a series of Tribal Gathering dates, and the gig was cancelled just 20 minutes before show time. He recovered quickly enough to play the rest of the Australian tour and it was the Hütter/Schmitz/Hilpert/Pfaffe line-up which brought the 3D shows into being at the end of 2011, although Pfaffe was discreetly swapped out for Falk Grieffenhagen in 2012.

In 2016, an American newspaper asked Ralf how long he intended to keep going. “The master plan is until I fall off the stage,” he replied and laughed.

Kraftwerk’s three albums from this period included some fairly extreme experimental music. But their output gradually tempered, from sound collages created in real time evoking war and destruction (‘Von Himmel Hoch’), through to more melodic yet still challenging soundscapes (‘Kling Klang’), and finally settling on the kind of pretty and atmospheric tunefulness which would go on to make up side two of ‘Autobahn’ (‘Tanzmusic’ from ‘Ralf And Florian’).