They’ve patched up their differences (again) and turned in a banger of a new album (as always) for which they enlisted the help of some morris dancers and Professor Brian Cox (like you do). You need to ask who? It can only be the brothers Hartnoll and the unstoppable Orbital

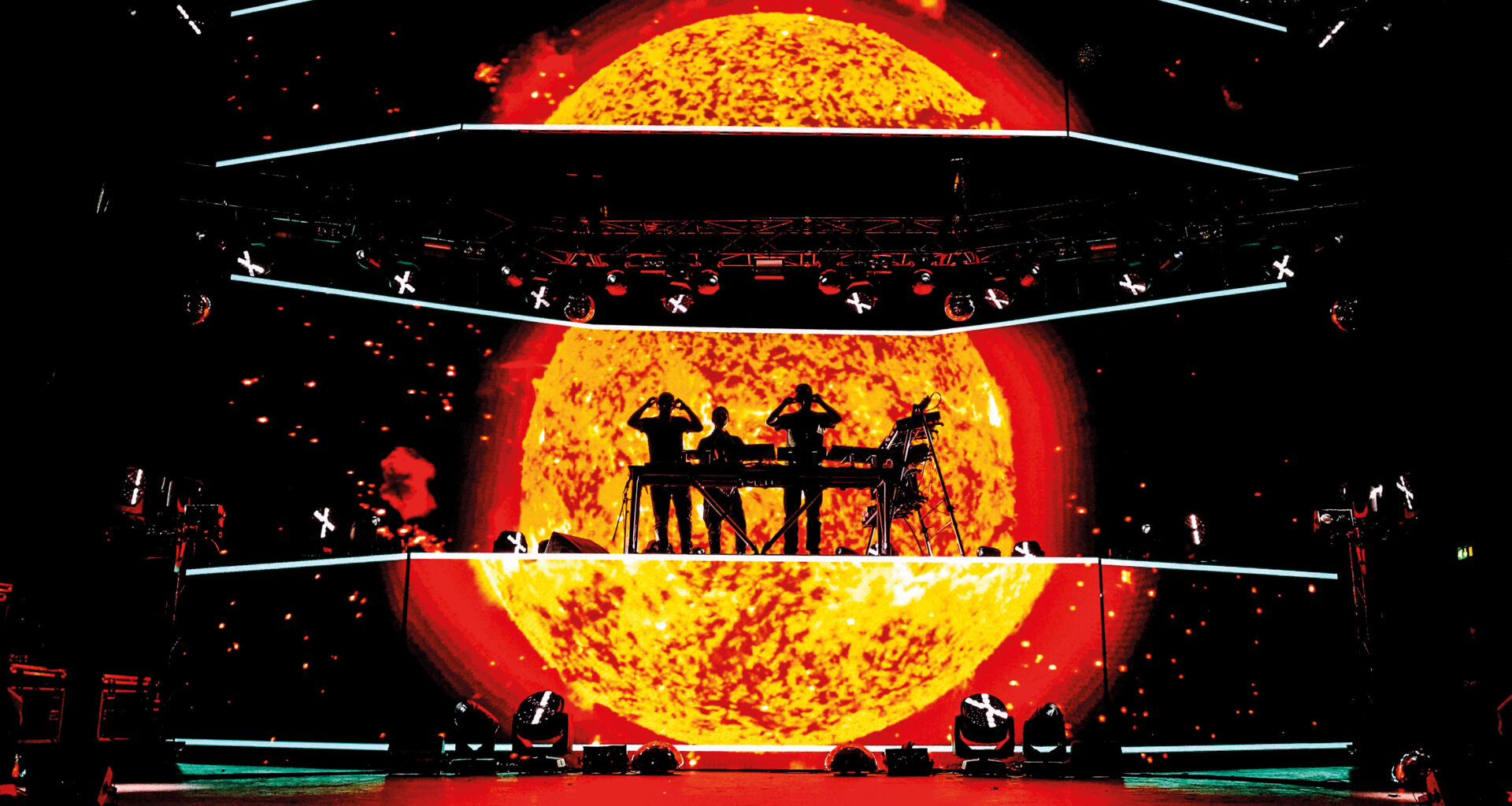

From Sevenoaks to the stars, from the M25 to the rings of Saturn, Orbital’s 30-year space odyssey has not always been a smooth ride. But between sporadic bouts of fraternal friction, Paul and Phil Hartnoll continue to make exhilarating electronic anthems with a uniquely British sensibility, and play the kind of explosively exciting live shows that few others of their vintage can match. On a good night, Orbital remain light years ahead of their peers.

Paul and Phil are currently back on good terms after patching up their most serious quarrel to date. Following a run of rapturously received shows over the last 18 months, complete with newly upgraded NASA-level visuals, the Brighton-based 50-somethings have finally learned how to cool their volatile chemistry. They were partly brought back together by the magical soothing voice of Professor Brian Cox, but also by a shared disgust for the current political climate.

Reunited and it feels so good.

The duo’s latest album, ‘Monsters Exist’, is a hearty feast of arena-sized bangers, cinematic sound paintings, barbed social commentary, and cosmic science-geek philosophy. In classic Orbital style, the album is a real grower, deepening its addictive pull with every listen. The title calls to mind a quote by the celebrated author, chemist and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi.

”Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous,” he wrote. “More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.”

Orbital were not aware of Levi’s words when they titled the album, though.

“No, but it’s bloody good!” Paul says. “My argument to that is, they are the monsters too. Just because somebody says, ‘I was only following orders’, that makes them no less a monster than the rest of them.”

Some of the real-life horrors that have inspired ‘Monsters Exist’ are Donald Trump, Brexit, Kim Jong-un and Jacob Rees-Mogg. But our enemies are not always so clearly defined, Phil points out. Sometimes we are the monsters.

“We are just saying to heed the warning,” Phil explains. “Monsters are out there, they look like us, and they are also inside us. Those little monsters that we swallowed up, they are there too, and you’ve got to acknowledge them.”

“There are broad brushstrokes, because there are monsters everywhere,”

Paul adds. “A monster can be massive, like Donald Trump or Kim Jong-un, or it can be small, like a school bully. It’s like a hazard warning sign. Monsters exist! Beware! Danger ahead! But to the Trump supporter, that monster may not be Donald Trump. We are all in our own little bubbles with our own monsters.”

As with previous Orbital albums, ‘Monsters Exist’ is well-stocked with boisterously euphoric electro beasts designed to get huge festival crowds bouncing. The timely political subtext is present, but subtle and elusive.

“I personally didn’t feel like doing a happy-clappy album,” Paul explains.

“I grew up on Crass and the Dead Kennedys, and it felt like now was the right time to do an angry record. But I also didn’t want to preach at people. I like music to be whatever you want it to be, which is probably why I like instrumental music. You can intellectualise it, but you’ve got tracks like ‘Hoo Hoo Ha Ha’, which on the surface is a very jolly track, but it’s almost on the edge of hysteria, like the carousel is going slightly too fast and might break.”

Emerging at the end of the post-punk, pre-rave 1980s, Orbital belong to a generation raised on Kraftwerk and Giorgio Moroder. It was an era when synthesiser music seemed inextricably linked to a bright sci-fi future of starship troopers and utopian disco modernism. But Paul insists the duo’s brand of steampunk retro-futurism has deeper, darker roots than that.

“I was born in 1968 and the Space Race was really big,” he says. “That was a real cultural topic – toys, games, television. It was massive in the 1960s. We grew up with ‘Lost In Space’, ‘Star Trek’ and ‘Doctor Who’. Even kids’ dramas were fucking mental, things like ‘The Changes’ and ‘Children Of The Stones’, this kind of folk horror. All those otherworldly, twisted things get into our music as well.”

The synthesiser was the perfect sci-fi geek instrument, Paul explains. It was essentially a “sonic spaceship” for generating extra-terrestrial sounds.

“All the noises, that is essentially what drew me to synthesisers and drum machines,” Phil agrees. “It just sparks my imagination when I hear an alien sound. We grew up with the first man on the Moon, so I had a space outfit and a Captain Scarlet outfit. I was there, flying around the skies.”

Orbital’s techno-futurist aesthetic has always had an emphatically English flavour, steeped in the droll humour and village green weirdness of Douglas Adams and John Wyndham, Gerry Anderson and The Clangers, JG Ballard and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

“I love Englishness,” Paul nods. “I find it funny. I’ve always lived in the south east of England and I’ve totally embraced stuff like Morris dancing and real ale. I guess I’m saying I’m a hobbit. I’m that indignant English character. I am Arthur Dent! That is what’s so brilliant about that character. It’s this crazy, trippy, science fiction story with this self-righteous Englishman in the middle of it all.”

One reason why Paul admires billionaire Tesla boss and aspiring space travel tycoon Elon Musk is because he blasted his car into orbit with a towel, a “Don’t Panic” sign, and a copy of ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy’ on board. So what if Musk offered Orbital a ride on one of his SpaceX passenger rockets?

“I’d be shit scared,” admits Paul. “I don’t even like riding a bike. But I would probably go. I don’t think I’d be able to turn it down actually. I’ve got great faith in Elon Musk, he’s the first person to make spaceships that actually look like something from Gerry Anderson. Those two booster rockets coming back to Earth and landing together in unison, how fucking smart was that!?”

Orbital have previously confirmed their nerdy sci-fi credentials with their 2001 reboot of the ‘Doctor Who’ theme tune, a guest appearance by former Time Lord Matt Smith at Glastonbury in 2010, and even a musical duet with the late Stephen Hawking at the 2012 Paralympics. But they’ve hit a new peak of geek on ‘Monsters Exist’ by hooking up with celebrity physicist Professor Brian Cox on the album’s epic closing track, ‘There Will Come A Time’.

Across a twinkly electro-acoustic backdrop, Cox calmly describes how human beings are essentially random clusters of atoms floating forever through the vastness of space. It’s a hypnotic, poetic, strangely moving sermon from the man who Orbital nicknamed “Brian Emo” in the studio.

“It starts brilliantly,” laughs Phil. “‘The one thing we can be certain of is, we are all going to die.’ Ha! You miserable northern bastard!”

The idea for this unlikely collaboration was sparked when Orbital and Cox both appeared at the science-themed Bluedot Festival at Jodrell Bank in Cheshire in 2017. The festival takes its name from Carl Sagan’s famous quote about planet Earth being a “pale blue dot” on the vast cosmic canvas. The Hartnolls initially suggested Cox might record a “cover version” of this speech, but Sagan’s estate were not keen.

“I was a bit unsure about the idea at first because you can’t really beat Sagan’s beautiful voice,” Phil says. “So Brian Cox doing it, I couldn’t see it working really.”

Ultimately, Cox ended up piecing together a text using lines from his own work. The result is a dreamy rumination on life, the universe and everything.

“It’s what we were talking about earlier,” Paul says. “That English sci-fi, quirky, almost retro-future thing. Brian is just brilliant, he’s the rave generation’s David Attenborough. Physics is slightly trippy anyway and quantum mechanics is mental! So the track is like a seven-minute slice of ‘The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy’. I even got the Brighton Morris Men involved, they’re in the background doing the chanting. It’s everything we’ve been talking about in one song.”

Monsters Exist’ is the album that many Orbital fans never expected.

The famously fractious Hartnoll brothers first disbanded in 2004, only to reunite onstage a few years later, leading to their excellent comeback album ‘Wonky’ in 2012. But after further disagreements, in October 2014 the duo announced that they were “hanging up their iconic torch-glasses and parting ways for the final time”.

As Phil returned to his globetrotting DJ career and Paul worked on various projects, including his ‘8:58’ solo outing and the ‘2Square’ album with Vince Clarke, the brothers barely spoke for three years. Why the extreme fall out?

“I can tell you a reason from my point of view, but there are many ways you can look at an experience,” Paul sighs. “From my viewpoint, the splits we’ve had in the past happened because I couldn’t work with Phil, because he was driving me mad! But nowadays, as a wiser man, I can also see that as my inability to cope with the situation.”

Phil meanwhile blames the tension on “general passive/aggressive stuff, not saying what you think at the time, letting things stew and fester, that type of relationship”.

“Paul’s always been a diva, throwing his toys out the pram,” Phil continues. “We used to call him Little Lord Fauntleroy when he was younger, so there was always something there! Ha! Paul is a bit of a – what do you call them? – a bit of a gammon! Those white middle-aged men who go red in the face talking about Brexit! Ha-ha!”

Now back on positive terms, Paul and Phil refer to each other with a mix of affectionate mockery and mild irritation, like lots of siblings. Would they be friends if they weren’t brothers?

“Woooo… who knows?” Paul ponders. “That’s a tough one to unravel because I’ve known him for 50 years, but I’m not going to bullshit, I’d say probably not. We annoy each other. So many people who aren’t in bands say, ‘Ooh maybe that friction is what holds the band together?’. Bollocks! That’s the thing that annoys both of us!”

So after their epic three-year sulk, the brothers finally patched up their differences for a string of live shows last year. It was during these gigs that ‘Monsters Exist’ began to take shape.

“For me, I just wanted to talk again,” Phil says. “I couldn’t enjoy all my past career if my brother wasn’t talking to me. He’s really lightened up and I can see him enjoying himself again, because it had got to a point where it didn’t seem like he was at all.”

Both Hartnolls insist they have now found a safety valve to ease the pressure that tore the band apart in the past. Phil admits he has learned to be less impulsive. Paul concedes he has become more tolerant.

“We’re on a nice, clean, level playing field,” Paul says. “I can see it now. It’s not about him, because you can’t change other people. It’s about me. I can manage it. I do believe that’s the way forward.”

“It’s exciting again,” Phil grins. “It reminds me a bit of what it was like when we first started. But we haven’t got to prove anything. Seeing Paul enjoying what we’re doing and relaxing is great. As his brother, I care about him a lot and I want to see him enjoy it. I’m not interested in doing this unless it’s going to be fun and exciting, and now it’s like I’m allowed to enjoy that dressing up box again. Onwards and upwards.”

From Sevenoaks to the stars, Orbital’s space odyssey is not over yet. Onwards and upwards indeed, to infinity and beyond.

‘Monsters Exist’ is out on ATP