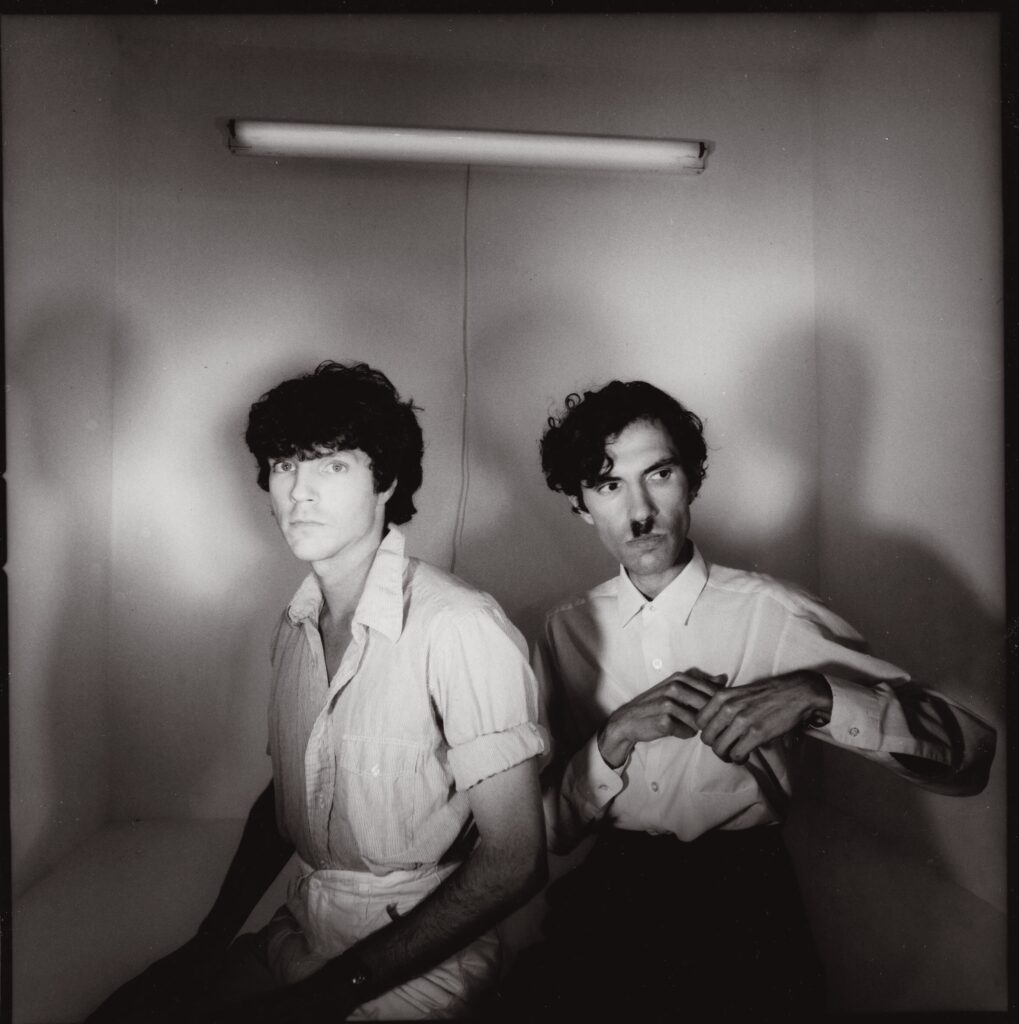

As Sparks mark the 40th anniversary of their disco opus ‘No 1 In Heaven’, Ron and Russell Mael wonder if it’s a disco record at all, explain how they bluffed their way to getting Giorgio Moroder on board, and reveal their Donna Summer epiphany.

When Sparks released ‘No 1 In Heaven’ four decades ago, it’s safe to say the world wasn’t quite ready for it. Record companies certainly weren’t. Tapes of the album, recorded with Giorgio Moroder, had been collecting dust on desks in A&R departments for the best part of a year before someone at the German offices of Virgin Records stumbled upon the recordings and flipped out. Where so many other labels had already passed, Virgin HQ in London soon recognised the album’s potential and the campaign to repackage a quirky American rock band in a disco world began in earnest.

“Everybody now tends to think it was an obvious album,” says singer Russell Mael. “But the sound was challenging, and oftentimes record labels aren’t the visionaries you would think they should be, and that’s even having the name of Giorgio Moroder – who was, you know, really successful with Donna Summer – attached to it.”

During the mid to late 70s, disco makeovers had been tried by everyone from the Bee Gees to Blondie; Rod Stewart to The Rolling Stones. But to take an act like Sparks and transplant them into the whole European electronic milieu was something new.

“People really weren’t ready for the record the first time around,” says songwriter and keyboard player, Ron Mael. “It puzzled people that we were moving away from a band format, doing an album that was song-orientated, but exclusively electronic.”

When ‘No 1 In Heaven’ was finally released in March 1979, it didn’t perplex everybody. Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols was a clandestine fan, according to Ron, and Paul McCartney on hearing the older Mael’s pronouncements that “guitars are dead”, repeated the line to the British music press and went on to make the sublime ‘Temporary Secretary’ the following year. There’s an argument too that with ‘No 1 In Heaven’ they created the classic synthpop duo archetype: an onstage dichotomy of outlandish frontman in the foreground, and silent, grumpy bloke at the back. Inventive or not, many critics remained unimpressed, with NME’s Ian Penman going as far as to proclaim: “Moroder’s production is essentially irrelevant”.

More surprising, perhaps, is the singer’s distancing of the band from disco itself, a genre that he says the brothers had no intention of emulating when they set out on their sonic adventure. I wonder aloud if Sparks had been concerned that the disco zeitgeist might pass before the record’s release, given the purgatorial previous year where a recording contract had been far from forthcoming. After all, ‘No 1 In Heaven’ was released just months before DJ Steve Dahl unleashed the Disco Sucks movement by staging Disco Demolition Night, where crates of vinyl by Labelle, Kool & The Gang and Earth, Wind & Fire were cremated or blown up at Comiskey Park, the former home of the Chicago White Sox baseball team.

“Hearing it again with fresh ears, I was kind of surprised by the complete lack of disco,” says Russell, having overseen the reissue of the record on the band’s Lil’ Beethoven label. “At the time, people threw around the loose term ‘disco’, and listening to it now, I really don’t see the parallels. I see electronics being used, but most of the rhythms are way too fast for it to be disco. If you listen to ‘Academy Award Performance’, it’s a really hyper song, and I’m completely baffled at anyone making that comparison.”

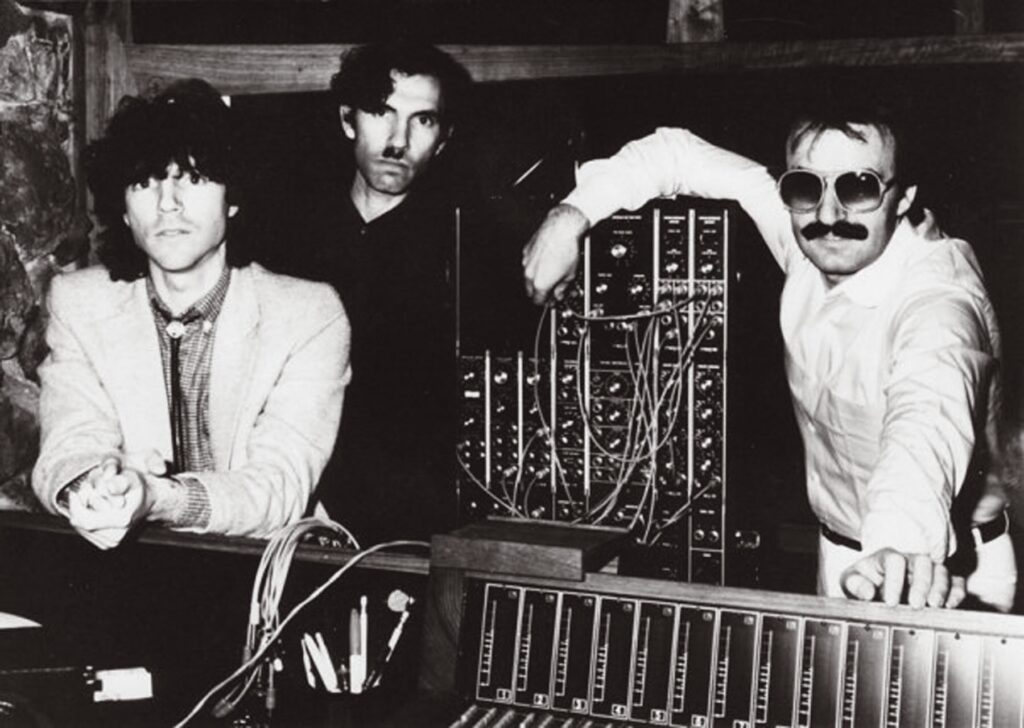

“We never really approached it as disco,” says Ron. “Our mentality was all about the sound. So we thought of it as an electronic album made by a rock band working in a song format. It was different from some of the electronic things being done. With Kraftwerk, the electronics shape the whole thing, and we’re huge fans of Kraftwerk, but we were approaching electronics with the intention of working our songs into an electronic format.”

But far from confusing the British public, the album yielded two Top 20 singles, their first hits since 1975, including the near title track ‘The No 1 Song In Heaven’. The other, ‘Beat The Clock’, started out as a Velvet Underground pastiche, and under the transformative hand of Giorgio Moroder, features an automated breakdown that might have inadvertently inspired the theme to Channel 4’s ‘Countdown’. It should be noted that composer Alan Hawkshaw says any resemblance is coincidental.

“The ‘Countdown’ theme didn’t need inspiration to write,” Hawkshaw tells me in an email. “It was done between other projects and rather hurriedly as I recall.”

The commercial success of Sparks led Virgin to use the Maels to write and produce for other artists, which begat the rather curious Noël’s ‘Is There More To Life Than Dancing?’, a mini-album that exhibited many of the attributes of disco: four-on-the-floor rhythm, a warmer ambience, and the lead single ‘Dancing Is Dangerous’, segueing into the title track like a Tom Moulton mix.

“These days, those kinds of projects are very hard to get past a major label, but at the time Virgin were really enlightened and willing to take chances,” says Ron. “We weren’t particularly known as producers at that point, but we’d learnt a lot from working with Giorgio.”

The project sank without trace, but the records have become collectors’ items among Sparks fans, and the collaboration has taken on its own mythology, particularly given the similarity in the vocal timbre of Noël and Russell.

“Oh I can categorically say it’s definitely not Russell,” says Ron, perhaps ending years of speculation, or perhaps not. “I was there. I’m a witness.”

The Maels, like many others, had an epiphany upon hearing Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ in 1977. Their collaboration with Moroder came about by mistake. More accurately, they were caught in a lie, which turned out to be fortuitous. A German journalist interviewing the band asked what they’d be doing next. “Oh, we’re going to be working with Giorgio Moroder on our new album,” they said, more in hope than anticipation, having never met or made contact with Moroder before. The journalist turned out to be a good friend of the Italian pioneer, and put them in touch once their red faces had returned to normal.

Another tall tale Sparks perpetuated was that they’d recorded ‘No 1 In Heaven’ at Moroder’s famous Musicland Studios in Munich. It made sense given the album’s overriding glacial electronic sound, but it had, in fact, been recorded at Sound Arts in sunny Hollywood. While Sparks, ever the contrarians, would go on to produce two of their most band-oriented albums, 1981’s ‘Whomp That Sucker’ and 1982’s ‘Angst In My Pants’ at Musicland, one of the finer moments on ‘No 1 In Heaven’, the phantasmagorical ‘My Other Voice’, actually arrived almost fully formed from Musicland in the shape of a backing track originally intended for the Queen Of Disco.

“It’s a strange one, because it was originally a Donna Summer track that Giorgio had recorded called ‘Journey To The Center Of Your Heart’,” says Ron, picking up the story. “He had a complete performance of Donna Summer singing that track, and for whatever reason it was never used for the eventual track that came out. I don’t know why. It was a really beautiful melody, and the chord changes are really interesting. So we actually used most of the music of that recording, and then tried to make it lyrically more related to the Sparks sensibility.”

“It’s also atypical of the songs on that album,” says Russell. “It has a special atmosphere. And I like the structure too, where it takes forever for the vocals to come in. Beyond the atmosphere, it’s a really odd structure and I like that.”

Another anomaly came in the shape of Peter Cook, who recorded a couple of comedy skits for promotional purposes that were originally available on the picture disc pressings of ‘Tryouts For The Human Race’ and ‘Beat The Clock’. These improvisational moments have been preserved for posterity on the double disc re-release of the album.

“That was just Virgin’s foresight,” says Russell, explaining how Cook came to be involved. “They were after something unique surrounding the album. They approached him and asked him to wing it, and I think they just stuck up a microphone and maybe some booze in the studio and said, ‘Go for it’.”

Sparks’ previous album, 1977’s impishly-titled ‘Introducing Sparks’ (it was their seventh LP), had not performed as well as they’d hoped. It holds up much better today than one might expect from a record made entirely with session musicians at a time where they were perceived to have painted themselves into a corner. Their eighth studio album would confound and delight, and in some cases horrify, such was the change in dynamic. Did it feel as though they were risking their careers at the time, even if the last couple of albums had underperformed?

“It’s probably a risk in a good way,” says Ron. “We’ve been on the edge of a precipice for almost all of our career. When we moved to the UK, we didn’t know how much pressure we were under at that point to deliver something. We felt we’d gone as far as we could with the band format at that time, so the ‘No 1 In Heaven’ album felt like a risk, but an exciting risk. Had we done it on our own it would have been ridiculous, but we were working with Giorgio Moroder. He suggested that we would actually be learning something as well as creating an album, which turned out to be the case.”

“Everything we do is kind of a gamble,” says Russell. “The whole of life is a gamble. But I think that things tend to work when one doesn’t know what the outcome will be.”

The changes also signalled a more meta approach to working for Sparks, who could extricate themselves from the constraints of convention at will, shapeshifting and emerging in other incarnations: as part of Franz Ferdinand, or the Swedish National Radio Department, or in the score of a Leos Carax musical…

“I suppose that’s right, yeah,” says Ron, “because the one real advantage that we had over other bands is that we were able to do that. That if we do put ourselves in other contexts, like working with electronics, or working with an orchestra, or doing work writing film musicals, people who are at least aware of us think that’s perfectly natural. It’s what Sparks do.

“But when we recorded ‘No 1 In Heaven’, we didn’t know where it was going or what the reaction would be. It’s kind of mind-boggling that it’s being re-released after 40 years and it doesn’t sound particularly of a time. That kind of electronic pop music has become such a part of the vocabulary of bands, and even performing without a traditional band is no longer not acceptable, it’s actually preferable.”

‘No 1 In Heaven’ is out on Lil’ Beethoven