They made punk music before anyone else. They made punk music better than anyone else. And they didn’t do it with guitars, they used battered old keyboards and cheap drum machines. From the mean streets of 1970s New York, Suicide broke every taboo in the book, getting themselves some nasty bruises along the way…

Suicide should have been one of the biggest bands in rock ’n’ roll history. When I interviewed Alan Vega and Martin Rev at the Columbia Hotel in London in 1998, Rev told me they’d been convinced there would be a bidding war to sign them when the duo debuted in 1970 under the banner “punk music from Suicide”.

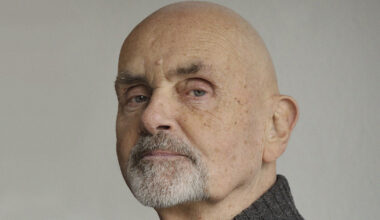

“We were still coming out of the age of the 60s, from stadium rock and beyond,” says Rev, speaking to me from his home in New York. “I said to myself, ‘Man, this shit, we could be as big as The Beatles’. I heard ourselves playing at stadiums for sure, to 60,000 or maybe 80,000 people with that sound we had. But, of course, reality is always something else!”

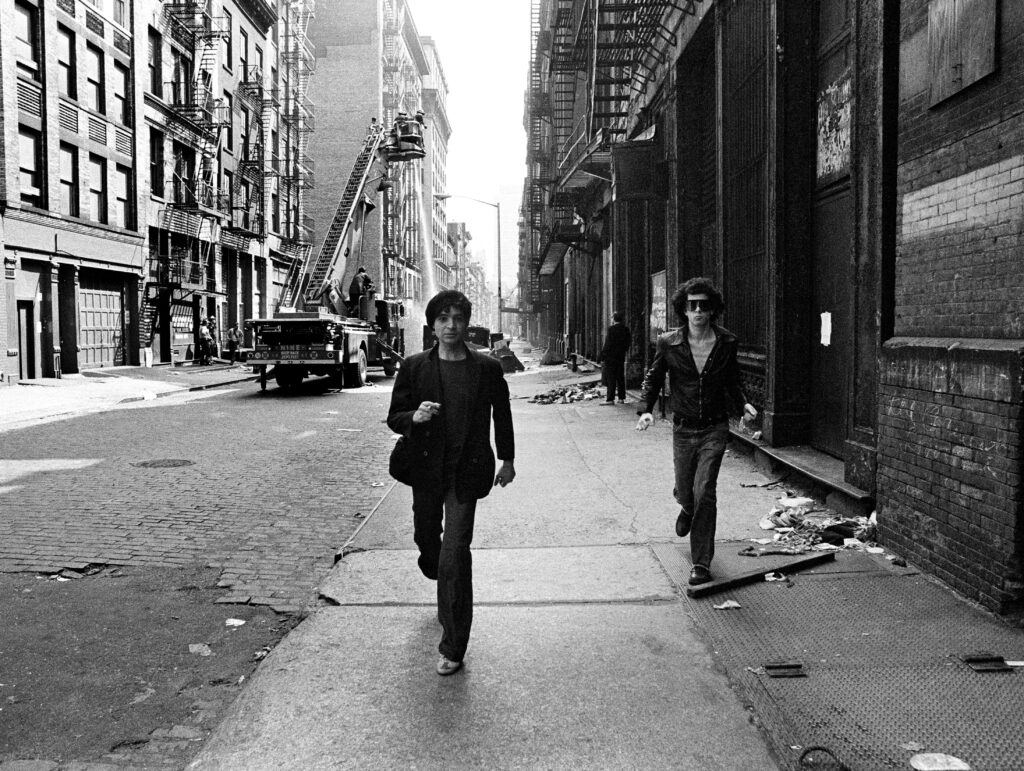

In terms of their significance, if not their sales, Suicide are indeed one of the biggest bands in rock ’n’ roll history. But theirs is a story of destitution, darkness, violence and despair, as well as improvisation with next to nothing, a fiercely futurist vision and, ultimately, recognition and vindication.

Right up until 2016, when Alan Vega sadly died at the age of 78, they were the last of the 1970s New York art rock revolutionaries to still be standing, pulsating, raging…

For those yet to be initiated into Suicide, Mute are preparing to release ‘Surrender’, a compilation featuring 16 of their best tracks. Taken from the five studio albums they issued between 1977 and 2002, the material has been remastered and the bonuses include an alternative version of their beautiful, horrific opus ‘Frankie Teardrop’. Now that the smoke of cultural history has cleared somewhat, it’s a chance to reassess their work away from the context in which it was originally released, with accusations ranging from unlistenable extremism on the one hand, to selling out on the other.

Suicide, like Kraftwerk, had a massive impact on the electronic 80s. Kraftwerk, who were benignly antithetical to rock ’n’ roll, eschewing its traditional instrumentation and its trappings in favour of synthesisers and conservative, business-like attire, were still considered robotic and phoney in the Luddite 70s. They were a fey and calculated insult to the fretboard wrangling and sweat and machismo considered the true marks of authenticity and quality in that decade. And yet they were widely revered and even entered the hall of fame.

Alan Vega and Martin Rev provided their own yin-yang, man-machine template that would be followed by a range of duos – Sparks, DAF, Soft Cell, Pet Shop Boys, Blancmange, Yazoo, Erasure and more. Despite that, they faced antipathy and hostility, most dramatically when an axe whistled just past Vega’s ear at a gig they played in Glasgow in 1978. They had always invited confrontation as a component of their act, but their crime was to break ultimate rock ’n’ roll taboos to get to their essence.

Suicide played the sort of joints Kraftwerk never did. They put themselves at the mercy of crowds who were appalled by their unabashedly stripped-down electronics, their lack of song structures, and yet had the effrontery to be fronted by a rock ’n’ roll animal channelling the spirit of Elvis Presley. Vega had idolised Elvis since playing ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ every day to motivate himself to go to school. Did the virulence of the audience response surprise Rev?

“It did the very first time, but not thereafter. It was the lack of any of the usual elements for people to relate to – guitar, bass, drums – as well as the intensity of what we were doing. Pure, instinctive… Certainly Alan, as a performer, his idea was, ‘Hey, I’m going from that, confronting the audience’. And the sound made perfect sense to me. The sound pushed him to react, to be even more antagonistic. And I would react too, to the effects of what he was doing. And then the audience coming back at us, whether it was booing or walking out, that just makes you play harder because you’re up against this resistance.”

Rev’s first ever participation in a band was as a kid, shaking marbles in a plastic container. It seems apt, given his later penchant for using minimal equipment to create full effects. In his formative years, he also sang doo-wop and developed a fondness for avant-garde jazz. He played keyboards – at one point he was mentored by the great blind pianist Lennie Tristano – and was a regular at the Village Vanguard club. I wonder if he was influenced by Sun Ra, who introduced electronics into the realms of modern jazz?

“Ironically, when I was doing a lot of jazz – this was in my own group before Suicide – I was very aware of Sun Ra, but I’d yet to hear his electronic stuff. I was playing more of a sort of ‘action music’ on an electronic keyboard, because most places you played didn’t have regular pianos when you went to do a gig. So I was in that arena. Playing free and electronically – like Cecil Taylor – which is what Sun Ra got into as well. Avant-garde music permeated the environment at that time – Coltrane, Ornette, Miles…”

What about Fluxus and the conceptual art scene? Vega’s pre-Suicide solo shows at Museum: A Project Of Living Artists, an open-all-hours space in Greenwich Village, saw him construct sculptures from fluorescent light strips which he would place down his trousers, then hurl himself out into the audience at the end of the performance. Was Suicide conceived in this arthouse spirit?

“We thought of theatre, for sure. That was something in the air that Iggy Pop brought to the fore. But it wasn’t a specific theatre. Artaud and living theatre… I’d been exposed to that, but I didn’t get onstage thinking in those terms. To me, it was about expressing what was right – what came out of the music, what happened onstage, what we felt onstage… I know I wasn’t thinking in terms of conceptual art, although I was aware of it. Stuff like photorealism was in the environment. The art world was post-pop at this point.

“But we didn’t work to preconceived ideas. A lot of what we did, certainly what I did, we only understood it after the shows. We saw what we were doing in retrospect. A lot of the energy came from living the life of a poor artist. And the electronics, which was still so fresh, that was a whole new frontier. That was what was driving me. The rock ’n’ roll came out of that, because it made sense to me. I put it in a rock ’n’ roll context early. We were doing really raw, free stuff. Alan was all screams and I was all post-Trane sound, conveyed electronically.”

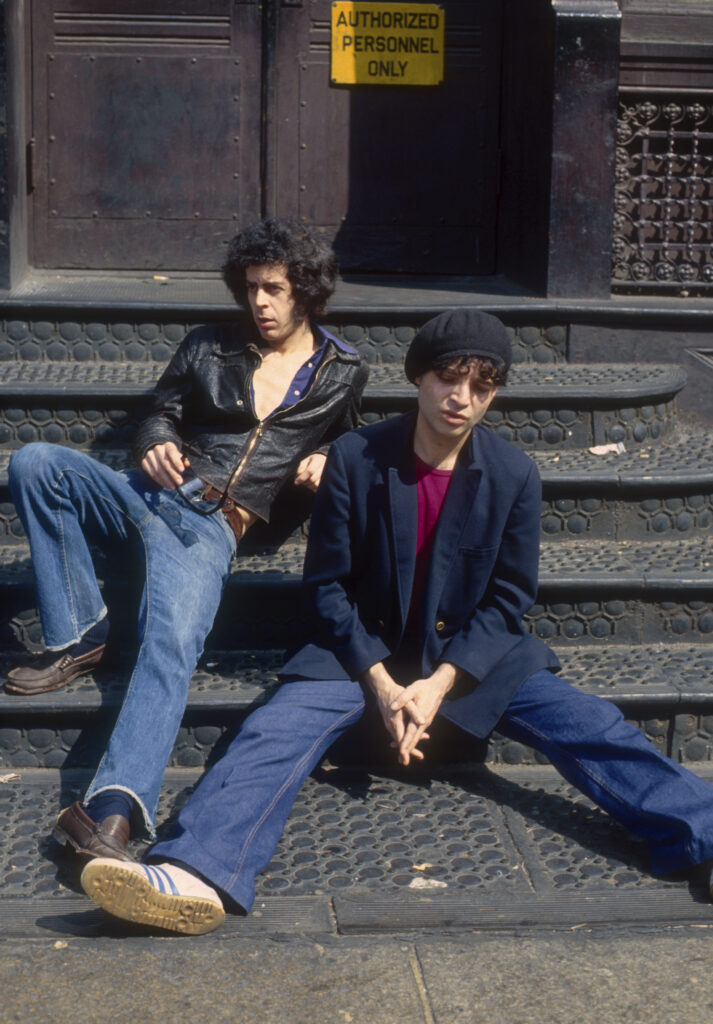

During the early 1970s, Rev started adopting his own crucial theatrical prop – huge shades, which gave him a studiously impersonal, almost Judge Dredd air as he worked his machines.

“I was finding these incredible 25-cent or 50-cent pairs of glasses out of bargain bins. I also liked particular styles of jackets. The visual component of being in a band was close to Alan and to me, so we wanted to take advantage of that. We made our own clothing. We saw everything as a costume. The way that people dress for classical music, for jazz music… I mean, a tuxedo is a costume too. From Elvis on, we’d grown up with great-looking bands onstage – the leather jackets, the motorcycle gear… That was part of my heritage.”

Heritage is the key word. In contrast to their futurism, Suicide were at heart subtly nostalgic. Theirs was a distillation of their 1950s halcyon days – doo-wop and rock ’n’ roll pouring out of every window and the iconography of Elvis and James Dean, all of it reworked and pared back to its most basic, essential, electric pulse, with the smothering flesh of commercial convention hacked bloodily away.

Despite the apparent yin-yang vibe of Vega and Rev, I suspect they were actually very like-minded people. Kindred spirits.

“We were,” says Rev. “That’s how we ended up doing this together. And when it came to our dedication towards art and being artists, we were both totally committed. Alan didn’t even have a place to live when I first met him. I was also on the street a lot of times. So it was difficult. We had no money because we lived for the art, for want of a better term. The agony and the ecstasy. We knew lots of other artists, but no one was as committed as Alan and me. Alan was totally on this dynamic. He saw himself as a visual artist, but he felt he wasn’t able to take it any further unless he performed. And I was the perfect link-up for him.”

There was a seven-year gap between Suicide’s first live appearance and their eponymous debut album. That said, 1977 was propitious. Suicide impacted not just in the slipstream of punk and a burgeoning Kraftwerk, but also Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’. And a few journalists were by now more receptive to their work.

“A few is the word! But, yes, people were talking about ‘punk’ by 1975 or 1976 and the record companies were coming around to it. But nobody was ready to sign us until Marty Thau, who had managed the New York Dolls, came in and started to manage us at the end of ’76 – and he had known us since the end of ’72! Of course, groups like the Dolls were making records much earlier than us, but we were not the darlings of that scene. Even Marty later said that he thought we were an incredible group, but he could never make a record with us. Then he caught us again in 1976 and he was struck again, so he asked if he could manage us.”

And yet, despite touring with the supposed vanguard of the new, Suicide found themselves a lightning rod for a conservative rockist antipathy. The gigs they played when they came to Europe and the UK were rowdy and chaotic affairs, the mania captured on ‘23 Minutes Over Brussels’, a cassette recording of a performance supporting Elvis Costello at the Ancienne Belgique concert hall that was subsequently issued as a flexi disc. The duo were roundly booed by Costello fans throughout and their set ended prematurely, when the crowd stole Vega’s microphone. Suicide were too much – even for the punks. Three chords good, one chord bad.

“Alan had been to Europe before, but this was my first time. I thought to myself, ‘Wow! Finally we’re going to get some recognition’. I’d read about American jazz musicians who had come to Europe and had at last been treated like human beings. And the first thing we did there – it was a real intellectual thing, a science fiction festival – the audience rioted. And from there on, it was more intense every night.

“The gigs supporting Elvis Costello were incredible. They had to be closed down. A couple of places were teargassed. And then, from the frying pan into the fire, we toured the UK with The Clash. They had difficulty playing because their fans had torn down theatres when they’d toured last time, so they had to play airport hangars and bare auditoriums, all these alternative places. But those audiences, you know, if they loved you, they got pretty violent. They’d be throwing things at you and rioting. The punk ethic, you know. I remember standing by the stage once to watch The Clash and seeing all the spit flying. We got that too – and more. And with a little more animosity! It was the electronics and the lack of guitars that set them off.”

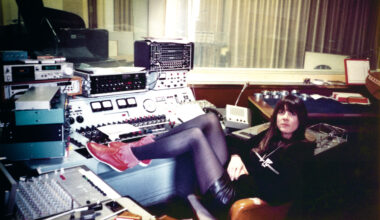

Suicide’s approach to electronics was singular. It was partly out of necessity – they had very little money, to the extent that they were virtually destitute – but it was also the aesthetic preference of wreaking maximum, distorted effect through simple modification. One of Rev’s earliest keyboards was a second-hand Japanese organ which he acquired for $10.

“I was using very basic equipment,” he says. “It was whatever we could afford second-hand – a single keyboard, an amp… I would set up a ride cymbal and a snare, so I could play drums over the top of what I was doing on the keyboard. What was essential were these little distortion boxes. I think Alan hit me onto those and I started plugging them in. They didn’t cost that much and they allowed me to get the sound I wanted. I’d found myself gravitating towards a deep bass sound on the organ when I was playing jazz. I’d be immersed in those simple notes, those bass sounds… I’ve always been a bass cat. Those electric pianos, they didn’t really have that bass sound, so I modified them and added a couple of things.

“It was all we could afford. Kraftwerk had better equipment than us. A lot of the groups did. Genesis and ELP had an incredible array of instruments. But we could never have had anything like that – carrying it around, storing it somewhere… So our instrumentation was the result of need, the same as with hip hop. Necessity created scratch, MCs, rap… Who could afford instruments? But if you had a turntable and a record, you could find a way to make new music. That’s what art is about.”

Another key acquisition in Suicide’s sound was the drum machine. While Kraftwerk used their wealth to develop innovative electronic rhythms, Rev’s sonic weapon of choice was basic, banal even, as described in Kris Needs’ biography of the band, ‘Dream Baby Dream: Suicide – A New York Story’:

“Every once in a while, you would get invited to someone’s wedding or confirmation,” Rev told Kris Needs. “Guys would be playing a keyboard piano or an accordion and using a rhythm machine. And they’d entertain the whole house. They couldn’t afford a band, so they got one or two people and used rhythm machines.”

This was a masterstroke. Of course, subject to various effects, distortions and extreme modifications, the mallet-like put-put of a dirt-cheap drum machine could discharge avalanches of sound, a tiny heartbeat amplified to nightmarish proportions, as on ‘Frankie Teardrop’, or provide a small but insistent jackhammer counterpoint, to the sentimentality of ‘Dream Baby Dream’ for example.

By 1980 and their second album, ’Suicide: Alan Vega And Martin Rev’, the band were still hanging in there, but now with a solid critical appreciation on both sides of the Atlantic. Vega had always talked up the pair’s “bubblegum” potential and the fact that their new record was produced by Ric Ocasek of The Cars proved the point. Opulent, playful, colourised, physically minimal yet maximally intense, it prefigured a new mode of pop being. Now signed to the world’s hippest label, ZE Records, Suicide seemed perfectly positioned to take advantage of the looming electronic boom.

It was to be other groups who capitalised on their hard work, though. So how did Rev feel about the likes of Soft Cell and the Pet Shop Boys attaining commercial success on the back of their example?

“It never upset me, but I felt it was a bit out of place,” he replies. “I felt we deserved the same or more. But if an audience or the industry is not ready for something… You can be the greatest thing in the world, but if they’re not ready for you, that’s how it is.”

Not that Vega and Rev were ever deflected from their mission.

“It’s the musical adventure that keeps you going,” adds Rev.

Alan Vega spent the 1980s enjoying a fruitful solo career with hits like ‘Jukebox Babe’, while Rev embarked on numerous projects of his own. They would come back together for three further albums, of which Rev finds himself feeling reasonably proud, having listened to them again for the purpose of putting together the ’Surrender’ compilation.

He should feel proud too. ‘A Way Of Life’ (1988), ‘Why Be Blue’ (1992) and ‘American Supreme’ (2002) received slightly mixed reviews in their day because they were assessed in relation to the ubiquitous electronic music of the era. Some Suicide fans might have preferred them to hammer away like it was 1977, but much as Rev’s ears had been open to the street sounds of doo-wop and rock ’n’ roll in his childhood, so they were to hip hop and house in the late 80s and beyond. Today, these later albums can be heard without being judged against the times they were made in – and ‘Surrender’ is an ideal invitation to do just that.

The absence of Alan Vega leaves an unspoken sadness in the air. So long denied, it’s strangely poignant that Vega was born just three years after Elvis Presley and could have been his kid brother, yet he only made his recording debut the year that Elvis died.

I can recall the bond between Vega and Rev when meeting them in London in 1998. Age was starting to catch up with them, but their futurism had not withered. Vega was excoriating about the landfill indie bands populating the lobby of that particular rock ’n’ roll vortex, despairing that new groups seemed more fixated than ever on the electric guitar. He spoke about his own achievements in the 1980s, merely lamenting, “I wanted that success for Suicide”.

For Martin Rev, however, to have engineered a living making the music he wanted to with the person he wanted to, suffices.

“You found a way,” he says. “You think of Wagner in exile, climbing the Alps to get to Switzerland with his piano strapped to his back. All the money we borrowed, the broken bridges of relationships… But that’s what an artist has to do, because he’s so tangential to the mainstream of life. We had both been doing this for years, as kids, before we were teenagers even, and that’s what made us happy, man. It’s love. And when you love someone, it drives you that way. You want to join with that force.”

‘Surrender’ is released by Mute/BMG