San Francisco, 1977. The punk explosion is peaking and Units are at the forefront of the vibrant and dramatic American West Coast scene. But these guys use synths not guitars. Throw in some weird and wonderful performance art concepts and you’ve got one of the most unique electronic bands ever. Units mainman Scott Ryser tells the tale

“I didn’t want a doctorate in electronic doodling. I wanted a synth band that kicked ass!”

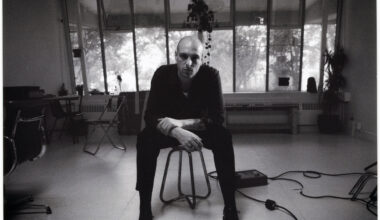

So says Scott Ryser, founder and mainstay of American synthpunk trailblazers Units. The band, who formed in San Francisco in 1977 and whose other core members included Rachel Webber, Tim Ennis and Brad Saunders, are perhaps best known for their ‘Digital Simulation’ album, originally released in 1980 and now given a long-overdue reissue on the Futurismo label.

Contemporaries of Devo, Suicide, Chrome and The Screamers, and with a career running concurrent with the synthpop explosion in the UK, even today Units’ music is as immediate and shocking as a two-bar heater falling in a bathtub. They were way ahead of their time, so it’s perhaps not surprising that their application of punk principles using electronics rather than guitars defies easy comparisons. There’s certainly little across the field of contemporary electronica that quite matches their serrated, confrontational style.

Arising from the world of performance art, they were a punk band in the true sense of the word, determined to break down the barriers between performer and performed-to, sitting comfortably alongside the likes of the Dead Kennedys as well as Gary Numan. Artistically purposeful rather than commercially opportunistic, they looked on as the anger of punk slowly dissipated, co-opted and codified by the record industry, and synth music gradually became ubiquitous. Units were done by 1984, but in the 30-odd years since then they have become legends and touchstones, revered and remixed by the likes of Health, Erol Alkan and Todd Terje.

To mark the reissue of ‘Digital Stimulation’, we asked Scott Ryser to tell us the Units story – and he does so with remarkable eloquence, great enthusiasm and very little prompting…

Units started in the punk era. Can you talk about what attracted you to synths rather than guitars?

“I was sick of the endless repetition of the guitar boy band formula. Guitar boy bands had been the norm for over 25 years when we started Units. And that was in 1977! So guitars had become a negative symbol to me. They represented ‘socially acceptable’ dissent for young people.

“McCulture condoned rebelliousness with a great marketing track record. As long as you held a guitar and jumped around like an ape, you could spout anti-Establishment poems while selling tons of hamburgers, beer and T-shirts to the Establishment. Somehow big business had taken Woody Guthrie’s guitar from 1943, the one on which he had written, ‘This machine kills fascists’, and turned it into a symbol of sex, fashion and entertainment.

“I wanted a synthesiser band, but I didn’t want a Kraftwerk-type elevator music band. I wanted a punk synthesiser band. And one of the crucial elements of setting out to create a ‘synthpunk’ band wasn’t just the synths and the time and place… It was also to create something that in some way challenged preconceived notions of the audience and performer relationship, and preconceived ideas of what pop music and performance should sound and look like.

“I wanted Units to be artsy, yet against the formal institution of the museum and art world acceptability at the time. Remember, we were in a DIY scene, but not DIY after you have been trained in an institution how to DIY. That’s why the synthpunk bands fitted in so well with the performance art scene in SF at the time. Because in the mid and late 70s, performance art was challenging preconceived notions of institutional art.”

A lot of your work involved performance art, including your “windows” show and a mock boxing match. Can you tell us a bit more about the kind of things you did? You say that you wanted Units to be “artsy”, so did you have a background in the arts?

“Units started life in San Francisco in 1977 and at that point we were a performance art group organised by my pal Tim Ennis. We incorporated music, dance, sound effects, film, poetry, and signs with slogans on them that moved across the room on motorised wires. Our pieces included props like hot air balloons made from garbage bags that we kept aloft with hair dryers. At that time, we called ourselves the Normalcy Roulette School of Performance.

“One of the members of our group, Ron Lance, was stage manager at the Mabuhay Gardens, a Filipino bar and restaurant on Broadway that had started putting on punk rock shows. When we went down there, we were blown away. Some of these artists, great new bands like Devo and The Screamers, were doing shows that were similar to what our performance group was doing. Only they were calling themselves ‘bands’ and they had a place to perform! It was really a no-brainer after that. We changed our name to Units and started calling ourselves a band instead of a performance group… and all of a sudden we had shows up the ass.

“The ‘windows’ performance was in January 1979, when Rachel Webber included Units in a show in the display windows of the JC Penneys store in San Francisco. Rachel was going to the SF Art Institute at the time and she and some of her friends there collaborated on the installation. She had painted the windows black, and then proceeded to scrape the paint away from the inside, slowly exposing Units playing our synthesisers while a bunch of punks in bathing suits danced in a mock beach party. Because of all the television, radio and newspaper attention it generated, I consider that event to be the beginning of the relative success that followed.”

Who were your principal influences in the early days of Units?

“The San Francisco art scene definitely had more of an effect on the idea of Units than any other contemporary music act. My musical influences were from synthesiser players like Walter Carlos, who later became Wendy Carlos. In fact, there was a large group of pioneering synthesiser players in the Bay Area at the time who influenced me.

“It’s interesting that at the same time the synthpunk thing was happening in SF, you had The League Of Automatic Music Composers working on experimental electronic music across the Bay at Mills College in Oakland. There was also an American experimental music tradition, as represented by fellow Californians John Cage, Henry Cowell and Terry Riley, among others. Terry Riley studied at San Francisco State University, which was the university I went to.”

Was it easy to lay your hands on the kind of equipment you needed? Did you have to do a lot of modifying?

“It was actually really hard to buy our synthesisers and our other equipment. They were very expensive and we were a bunch of poor kids. I bought the first Minimoog that came into Don Wehr’s Music City in San Francisco in early 1972. The people at Moog wrote the Minimoog serial numbers on them with a Sharpie pen back then. Mine is 1342. I had to sell my pick-up truck and use my paltry savings in order to buy it.

“Tim Ennis got his Arp Odyssey when about 10 friends chipped in and bought it for him as a present. Rachel Webber went through a few synthesisers before getting a Moog Source. By then, Moog were selling them to us wholesale. I did a lot of modifying on my Minimoog, which I still have. I put in an extra output jack, added an infinite sustain switch, and added a couple of other switches that I honestly don’t even remember what they do anymore. I also ran it through a Sequential Circuits Model 800 Sequencer that was an incredible pain in the ass to programme live before each show – once unplugged, it lost everything – and an Echoplex tape machine.”

A lot of punks were openly hostile towards synths. Suicide were bottled off when they toured the uk with The Clash, for instance. did you ever get an adverse reaction for using what some people might have considered to be “anti-rock” machines?

“It wasn’t a confrontational situation between the guitar fans and the synth fans in the West Coast punk scene when it started, because we were actually all anti-rock. We jammed with a lot with people from other bands… Dare I say it, we even jammed with guitar players. So while it’s true that Units were the first punk band to perform in SF using just synths, nobody in the scene at that time seemed to raise an eyebrow over it.

“Had we started playing shows in any other city, I do think that people probably would have been pissed at us and thrown bottles at us. But because this was San Francisco – pre-AIDS, openly gay, lots of sex, lots of drugs, a place where there were plenty of people doing much weirder things than we were – the audiences didn’t seem to react to us any differently than they reacted to anyone else.

“On top of that, when we performed we often distracted people from focusing on the synths. For example, the first time we played with the Dead Kennedys, we put this big movie screen we’d made from the metal hood of a Cadillac car on the stage. We set our synths to play a factory drone sound all by themselves, then we projected images of hated politicians, irritating authority figures, products from obnoxious adverts and the like onto the car hood, and then beat the hell out of the hood with lifesize guitars we’d cut out of plywood. We made the guitars so they would shatter on impact. Pieces went flying into the audience and people then threw them back up at the projections… We were lucky nobody got hurt or sued us.

“That night, Jello Biafra from the DKs was diving into the crowd and they stripped him… He ended up finishing the show naked. I honestly don’t think anybody in the audience that night woke up the next day thinking, ‘The DKs play guitars and Units play synths’.”

You supported a lot of uk artists when they toured the us, including Gary Numan, Ultravox and Soft Cell. What did you make of those guys? How did you get along with them?

“I liked the music of all the UK synthesiser bands we played with, although I didn’t consider any of them synthpunk. I especially liked The Psychedelic Furs’ music and they didn’t even play synths. I probably got to know Andy and Paul from Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark the best. They’re really nice guys and they even let me play on some of their gear. They were one of only a few bands that had a Mellotron back then. Although we never shared a stage with Bill Nelson, he did produce two albums of ours and we lived with him for at least a month. Great guy. Although he’s known for playing guitar, he’s an excellent synthesiser player as well. He’s also a great drummer.”

Did you ever feel unfairly overshadowed by the British synthpop “invasion”?

“I definitely felt overshadowed, but I never thought it was unfair. I loved Soft Cell’s ‘Tainted Love’, The Human League’s ‘Don’t You Want Me’, Eurythmics’ ‘Sweet Dreams’… All of a sudden, there was lots of really great synthesiser music on the Top 40 radio shows. To this day, I still love listening to those songs. But making a Top 40 pop song was never what Units had set out to do. We had set out to make performance art. So luckily, it never bothered me.”

By the mid-80s, synthpop was pretty much ubiquitous, so much so that Kraftwerk effectively gave up recording. Their work laying the railroads, so to speak, was done. Was the dominance of synthpop a major factor in units discontinuing after 1984?

“By around 1981, we were getting pretty popular, but we felt like our culture had absorbed the rebellion and dissent of punk music and was selling it back to the masses as fashion and entertainment. Punk was dead at that point, as far as I was concerned. People just wanted entertainment. So I thought, ‘What the fuck… I have this popular synthesiser band and I’m already touring with really popular synthesiser bands from the UK… We’ve just been signed to Epic Records… So why not try and write some synthpoppy hit like the rest of them and make some fast cash?’

“But in the end, I just couldn’t do it. It was like pretending to be Elvis Presley and singing karaoke! It didn’t inspire me and it wasn’t fun. It didn’t help when the head of A&R from the record label flew out to the UK, where we were recording, and had us sit down and listen to Michael Jackson’s new album, and said, ‘Can’t you sound more like this?’.”

In terms of its themes and its style, do you feel your music anticipated the cultural, social and even political trends of the 1980s? That it was genuinely “futuristic” in that respect?

“I feel like it was genuinely futuristic in the sense that we set out to make music that hadn’t been made before. I also think our lyrics anticipated social media relationships and technical addiction. As far as I’m concerned, it anticipated more of what was happening in the 2000s rather than the 1980s.”

What do you think about the current american EDM scene? Do you feel in any way vindicated? Or do you feel that too much of the original synthpunk spirit is missing in EDM?

“Back in 1977, I would have never thought in my wildest dreams that the current electronica scene would exist like it does now. As for the ‘original synthpunk spirit’ and whether that is missing in EDM, sure it is. EDM is often performed by some lone dude with a computer in front of a large anonymous crowd.

“But I still really like EDM for other reasons. First off, I love how many of the new electronic musicians are constantly trying to push the envelope of creating new sounds and beats. I love the idea of remixes, of taking the status quo and mixing it up in your own way… It’s kind of like sound graffiti. And what could be better than a huge room full of people dancing to synthesiser music? It’s a dream come true.”

‘Digital Stimulation’ is out on Futurismo