It’s synonymous with the sleek sound of the 1980s, and while you might know its name, what actually is a Fairlight CMI?

When Thomas Dolby got his advance from EMI in 1981, he immediately made two large purchases. One was a flat in Fulham, the other was a Fairlight CMI, the sampling wonder machine that was taking over the sound of popular music. Of the two, the Fairlight was the more expensive purchase – by a country mile. Today, you can install a Fairlight app on your phone for £9.99, while a property at the “affordable” end of the housing market in Fulham will set you back around half a million quid.

But that’s not the point. The Fairlight was a tool that shifted pop music into a new era and enabled the manipulation of sound to a degree unimaginable before. It was worth every penny to the various musical grandees and high-end studios that invested in one in the 1980s.

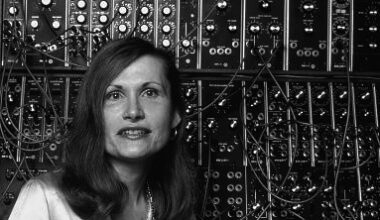

With its chunky computer block, featuring large format eight-inch floppy drives for disks loaded with orchestral samples and the like, the clickerty-clackity QWERTY keyboard, the iconic green-on-black computer screen on which you could draw your own waveforms with a light pen, and the six-octave keyboard, the Fairlight was the true herald of the computer music age.

This was a musical instrument that could replicate any sound and allow you to play it on a tempered keyboard, but the idea itself wasn’t new. The Mellotron had given a glimpse of what was possible with recorded sound playback technology, but it relied on fragile magnetic tape strips, and clunky and unreliable mechanisms. And if you wanted a new set of sounds, you’d have to have them made for you by a specialist studio.

New violin tapes would involve hiring a string section, a studio and an engineer who knew how to create the tape looms. Not cheap. The Fairlight used emerging computer chip technology to make the process as easy as plugging a microphone in, hitting the record button and recording any sound you fancied. Cue many belch-driven studio “experiments”, symphonies created by engineers saying “Bollocks” and dog bark ditties, swiftly followed by the extraordinary new sounds to be found on albums by Peter Gabriel, Kate Bush, and a veritable flood of mainstream stars.

The Fairlight was developed by Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie, two electronics engineers from Sydney, Australia. Ryrie was a synth head who published a magazine called Electronics Today International, for which he’d come up with DIY synth kits that electronics magazines were keen on in the 1970s. The pair soon teamed up with Tony Furse, who was working on a digital synth using Motorola chips. Together, they would make a truly groundbreaking digital synthesiser.

When the trio finally brought the Fairlight out of the lab after four years in development and started to introduce it to the world in 1979, the machine was actually a compromise, the result of a failure to make the digital synthesiser quite the way they’d wanted to. The use of samples to give the Fairlight users digital waveforms to manipulate was, they felt, “cheating”. Did they have any inkling that what they had come up with would revolutionise modern music making?

“No,” says Peter Vogel. “I had no idea what was to come. I thought it would be a fairly niche thing, like a Moog at the time.”

Robert Moog himself, the father of synthesis, was deeply impressed by the Fairlight, describing it as “by far the most intuitively efficient and satisfying tools for manipulating sound that I’ve ever used, and that includes modular synthesisers”.

Like any new technology, taking it to market was the key to success, and to recouping the investment they’d put into it. Vogel took the prototype Fairlight on the road in 1980, booking appointments in studios and attending trade shows and putting it through its paces in front of open-mouthed industry insiders.

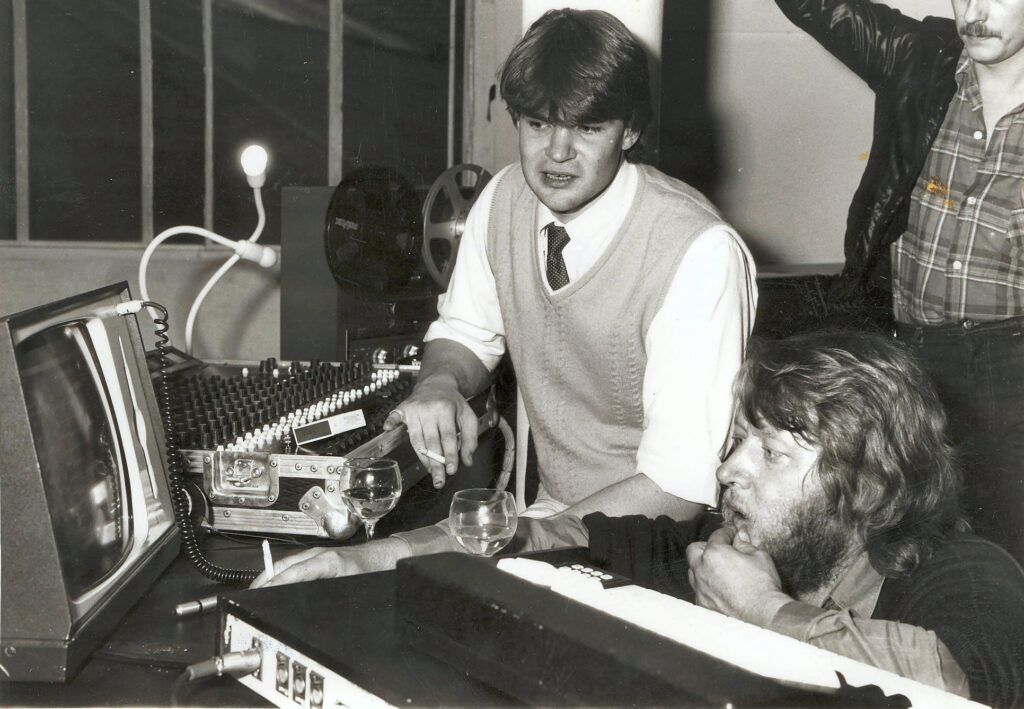

“I was showing some people the prototype at a studio in New York in 1980,” remembers Vogel. “Larry Fast was doing some work there. Someone suggested Larry would be interested in this sampling thing, so I invited him in to have a play. He called Peter Gabriel and said, ‘You won’t believe what I’m looking at…’ and held the telephone near the speaker and played some sampled sounds.”

Gabriel was thrilled by what he heard, and by the creative possibilities it suggested. He was working on his third solo album at the time, and asked Vogel to bring the Fairlight to the UK.

“The next thing I know I’m at his house in Bath,” says Vogel. There are photographs from that encounter. A microphone is set up in the grounds of Gabriel’s house, pointing at a crate full of glass which he is clearly relishing smashing with a sledgehammer.

“He was like a kid with a new toy,” remembers Vogel. “He was very excited and wanted to explore every possibility of the Fairlight. He got the idea immediately. It was like he’d been dreaming of such an instrument forever.”

Gabriel was so taken with the Fairlight that not only did he use it all over the album he was working on (and even more on its follow up), but he also asked Vogel if he could distribute the Fairlight in the UK. Gabriel formed a company called Syco Systems and started hawking them to his affluent musician pals.

“He was certainly a fantastic ambassador and he had brilliant ideas how to use the technology musically, which others then adopted,” says Vogel.

One of Syco System’s first customers was Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones, a long-time electronic music enthusiast, and Vogel personally delivered the Fairlight to his studio. He also dropped one off at Stevie Wonder’s place.

In 1982, the Fairlight Series II was introduced and with it came the software update which gave users the legendary Page R, an integrated sequencer that was relatively easy to use. This was the first time sampling and computer sequencing were available in the same machine, and it ignited a revolution in music making.

It was now possible to put together entire albums with the Fairlight; it could generate beats, rhythm loops, weird atmospheres, and be played like a piano or synth, and everything could be locked into strict time. The age of digital computer music, which continues to dominate studio practice to this day, had arrived.

The first important record to use a Fairlight was Kate Bush’s ‘Never For Ever’ in 1980, and it started turning up on stages, played live by Stevie Wonder, yes, and other well-heeled show-offs. The Fairlight dominated Peter Gabriel’s fourth solo album, released in September 1982, and Kate Bush used it to create a set of impressive and dense soundscapes around her compositions on ‘The Dreaming’ in the same year. The album was received with bafflement at the time, but is a classic of the sampler age.

Trevor Horn put it through its paces for the Yes hit ‘Owner Of A Lonely Heart’ in 1983 and Art Of Noise’s debut album, ‘Who’s Afraid Of The Art Of Noise’ positively rinsed the Fairlight for all it was worth, as did the Frankie Goes To Hollywood records. The Fairlight was Horn’s not-so-secret weapon. Fairlight library samples that came with the machine were soon all over the pop music of the age, from Michael Jacskon’s ‘Thriller’ to Yello’s ‘Oh Yeah’.

Even Joni Mitchell got on board, going as far as to say that, with the Fairlight, she could improve on the performances of professional string players.

“They can drag time,” she claimed, “but with the Fairlight you can get your whole string section really swinging. It’s an awesome machine. Can you imagine if you turned loose Mozart and some of those guys on this machinery? It would be boggling what they could do.”

The Fairlight’s success prompted American synth company New England Digital to add sampling to their high-end digital synthesiser, the Synclavier, which gradually morphed into something of a “tapeless studio system”.

“The Synclavier pioneered FM synthesis and a whole new sound was possible using that technique,” says Vogel. “Once Fairlight entered the scene, New England Digital added on the sampling capability. It had much better audio quality than Fairlight, at least until we completed the Series III, but the colouration that the Fairlight’s poor sampling quality introduced was actually the thing that gave it a unique and very musical quality.”

Krafterk plumped for a Synclavier system, using it on the painfully long recording process of ‘Electric Café’, which was finally released in 1986, while E-Mu Systems launched their Emulator in 1981. New Order used an Emulator to sample ‘Uranium’ from Kraftwerk’s ‘Radio-Activity’ album on ‘Blue Monday’ in 1983, one of the first instances of lifting a sound from one record on another.

As the 1980s progressed, more people got their hands on a Fairlight. Al Jourgensen of Ministry managed to buy one with his advance when Ministry signed to Sire. That Fairlight was hammered, probably literally, by the roster of Wax Trax!, who used its sequencing and sampling capabilities to create a slew of records which defined the aggressive and fun sound of industrial music in the second half of the 1980s.

In 1985, Fairlight were proud to announce that London’s Battery Studios (formerly Morgan Studios, where Led Zeppelin, Paul McCartney and Pink Floyd had all made records), had bought no fewer than four Fairlights, but the writing was already on the wall. The Japanese company Akai hired English electronics genius Dave Cockerell, who had been one of the three founders of the British synthesiser company EMS back in the late 1960s in Putney.

Their first sampler, designed by Cockerell, was the rack mounted S612 in 1985. It was an extremely limited machine compared to the Fairlight, but a year later Akai launched the S900, another rack mounted sampler with a price tag that was a fraction what you’d pay for a Fairlight. By the time the S1000 came along in 1988, it was obvious that the future of sampling wasn’t with Fairlight.

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

In a textbook playing out of the maxim “pioneers get the arrows, settlers get the gold”, Fairlight went bust in 1989, having never turned a profit. In the 1990s, Akai’s samplers could be found in every studio in the world, hooked up to Atari computers (later Apple Macs and PCs), sequenced with (more often than not cracked) copies of Cubase and Cakewalk software.

The Fairlight defined a generation of music making, the sound of the charts was dominated by those orchestral hits, samples of things being broken, slowed, reversed and processed, all locked into the excitingly rigid Page R sequences, all produced in some very high-end studios.

The Fairlight wasn’t a transparent instrument, it coloured the sounds it reproduced. It was one of its major limitations, but, as is often the way, that limitation became an essential part of its unique character. But the sound fell into disrepute towards the end of the decade, and the machines became, like the huge modular synths of the late 60s and 70s, white elephants, relegated to storage and worse.

As time passed, in the same way that a combination of nostalgia and rueful reflection has lead to a renaissance in analogue synthesiser technology, the Fairlight has become the subject of affectionate retro-gazing.

As the 21st century got into its stride, Peter Vogel started receiving an increasing amount of emails from distraught people around the world whose Fairlights were starting to malfunction. Where could they get their light pen fixed? Are there any replacement eight-inch floppy disc drives to be had? The answers, unfortunately, were “You can’t” and “No”.

But the interest in the Fairlight did make Vogel think that perhaps there was scope for a new Fairlight. And so he developed the CMI-30A, a replica of the original Fairlight, complete with the big computer box and the green on black screen with the light pen, but with 21st century technology driving it.

“I started developing the CMI-30A in 2009,” says Vogel, “the 13th anniversary of when I delivered the first exported CMI to Stevie Wonder. It was intended to be a limited edition of 100 units, each signed by me and Kim Ryrie.”

They started taking and shipping orders in 2011, paying a licence to the larger company which then owned the Fairlight trademark. Just as they were getting into their stride a complicated trademark dispute forced Vogel to stop production.

“Only 14 were ever sold,” he says, “so it was a bit more of a limited edition than I had hoped, and I have sued for the massive loss I made. Five years later, that case is still before the courts. It’s a tragedy, for me financially, and for the enthusiasts who wanted to own this bit of history.”

The Fairlight story isn’t over yet, and Vogel says he’s in talks with more than one filmmaker about turning it into a documentary. The tale of how a trio of unlikely nerds from Sydney changed the sound of pop music and the course of music technology itself could make for a compelling and potentially hilarious celluloid experience. But who would play Peter Gabriel? Answers on a postcard, please…