Featuring iconic record sleeves by the late Hull-born photographer, a new exhibition, ‘Trevor Key’s Top 40’, opens at the city’s art school, where he studied, later this month. We doff our cap to the great man

Trevor Key’s best-known image may well be Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’, but he was no one-hit wonder, producing a raft of instantly recognisable record sleeves for the likes of Can, Tangerine Dream, Joy Division, New Order, Sex Pistols, Ultravox, Roxy Music, China Crisis, Peter Gabriel, Section 25, OMD and even Derek And Clive.

As part of the year-long Hull City Of Culture celebrations, ‘Trevor Key’s Top 40’ is a fitting tribute to the photographer who died from a brain tumour in December 1995, aged just 48. Many of his masterful pre-Photoshop images feature in the show and they continue to baffle and amaze in equal measure. When asked how he achieved particular techniques, which he often was, he’d smile and mutter something about “magic”. Which indeed it was.

Key began his professional life as assistant to still life photographer Don McAllester, working on The Rolling Stones’ ‘Let It Bleed’ sleeve in 1969. He kept the famous Delia Smith cake that featured on the cover, carting it from studio to studio for years. He never threw anything away, claiming “you never know when it might come in handy”.

It was Sue Steward, a press officer at Virgin Records, who suggested Key as a candidate to shoot Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’ sleeve. The whole thing could have been very different as Virgin boss Richard Branson was quite taken with a manipulated shot of a boiled egg dripping with blood, which Key had in his portfolio.

Thankfully, Oldfield hated the image, but Key was hired to produce some new work, spending hours on a freezing Sussex beach shooting seascapes. The “bent bell” was a model Key had made and then shot in his studio to resemble an air-brushed painting before superimposing it over the seascape. Oldfield loved the result and Key pocketed the princely sum of £100 for his trouble.

Much of Trevor Key’s work is notable for its collaborative nature, which began in full effect when he met fellow music photographer Brian Cooke. Working as Cooke Key Associates, the pair became Virgin Records’ go-to dynamic duo, creating not only countless sleeves, but also coming up with the label’s distinctive ‘scrawl’ logo. It was around this time they were introduced to an unknown designer called Jamie Reid, who was working with a new Virgin act called Sex Pistols. Key and Cooke ended up getting their hands dirty with just every piece of printed material used by Virgin to promote the Pistols.

A further fruitful partnership began in 1979 when Key met a young, in-house designer at Virgin’s offshoot label Dindisc.

“I’d never really commissioned a photographer,” Factory Records’ designer-in-chief Peter Saville told Creative Review of his first meeting with Key. “I didn’t know anything. I was 24 and still finding my way. Trevor knew the business inside out and he, generously, took to me and where I was coming from very positively.”

The pair produced many an iconic sleeve, including New Order’s ‘Low Life’, which was the only cover to feature photos of the band themselves (“They never really believed those photos would end up on the cover,” Peter Saville told The Guardian in 2011. “The next time I saw them they said, ‘You bastard’. I don’t think they liked the sleeve.”) and their stunning ‘Technique’ cover, which featured a garden ornament that they spotted in antiques shop on Pimlico Road.

That Trevor Key isn’t better known is a travesty and it’s clearly something this exhibition hopes to address. It has lovingly been put together by graphic designer and creative director Scott King, who worked on ‘i-D’ magazine and ‘Sleazenation’, Key’s partner, the stylist Lesley Dilcock and Key’s former studio assistant, still life photographer Toby McFarlan Pond.

“I’m from Goole near Hull,” explains King. “So when I knew Hull was going to be the City of Culture I thought, ‘I hope they do something about Trevor Key’. I didn’t know Lesley and I didn’t really know Trevor – I’d only spoken to him on the phone, but I knew Toby and so I asked him if there was a possibility to do something. It ended up in this proposal where we’d pick his 40 best sleeves and put them in a kind of Woolie’s record rack.”

We invited Ian anderson of the Designers republic to pick out his favourite key moments

Mike Oldfield

‘Tubular Bells’

(Virgin)

“‘Tubular Bells’ was my first grown-up album. By a week. I didn’t get ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ first, because a friend already had it. ‘Tubular Bells’ wasn’t like the pop albums I bought by Bowie, Roxy, T.Rex and Slade. Neither was the cover. Although I stared at it for hours, I don’t think I spotted the crashing waves below the ‘monolith’ for months such was the iconic presence of what I assumed to be a tubular bell. At his best, Trevor Key created simple, clever-but-never-smartarse images that changed the way you saw the world and how you could represent it.”

Sleeve design and photography: Trevor Key, 1973

CAN

‘Unlimited Edition’

(Harvest)

“Can’s ‘Unlimited Edition’ compilation is a re-run of 1974’s ‘Limited Edition’ (the one with the white mice in a doll’s house with some sauce on the wall). On the surface it’s quite a different proposition to ‘Tubular Bells’, being ostensibly a ‘Sesame Street’-esque cut and paste repetition of each of the four Cans, but of course, ‘Tubular Bells’ was also a montage. That big UFO thing wasn’t really hovering over the surf, was it? What I really like about the cover of ‘Unlimited Edition’ is it’s a bit shit, as in gloriously pre-tech clunky like our early TDR BC (Before Computers) sleeves. Craft before craft was a beer. Handmade technology. Like Kraftwerk.”

Cover: Trevor Key, photo: Mick Rock, 1976

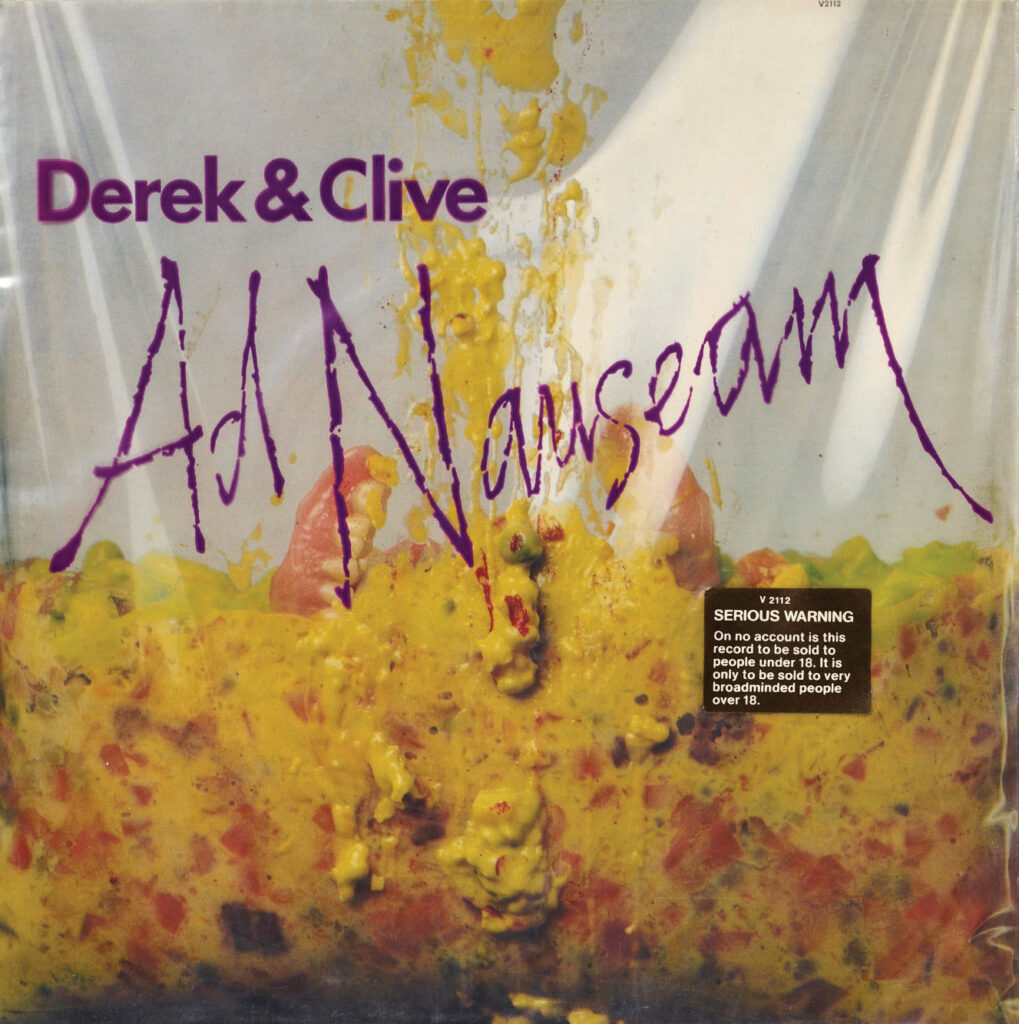

Derek And Clive

‘Ad Nauseum’

(Virgin)

“What sleeve designers sought was impact. Something that jumped out from the racks and, in the context of an LP, held your attention for the duration of both sides. Essentially all packaging needs a hook to get noticed and a gag to be remembered by. ‘Ad Nauseum’ gloriously scraped the cultural bowels of 70s British nonsense conservatism, out-puking punk rock by going straight for (and up from) the throat. I only recently found out Trevor Key shot it, which is interesting as it also out-punks his comparatively insipid work for Malcolm MacLaren’s ‘Swindle’-era Sex Pistols Flying Circus.”

Cover by Trevor Key and Cooke Key, 1978

Section 25

‘From The Hip’

(Factory)

“I always used to think this was one of my favourite covers, although I was less than a fan and never bought the album originally. Before the internet, if you didn’t have the album then you didn’t have access to the artwork, which is the reason why I could allow my read-only memory to shapeshift half-remembered imagery into the album cover I’d always wanted it to be in the first place. Such was ‘From The Hip’. Ostensibly based on land and topographical surveying poles, to me it evolved into a hyper-detailed analogy for marking our space in time, reflecting a sense of determining where we are and perhaps why. Looking at it now, I think it’s a great narrative, but really it’s just a nice image spelling out ‘From The Hip’ across the colour-coded poles (see New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’). Compromised, let’s say, by the type.”

Designed by Key/PSA, 1984

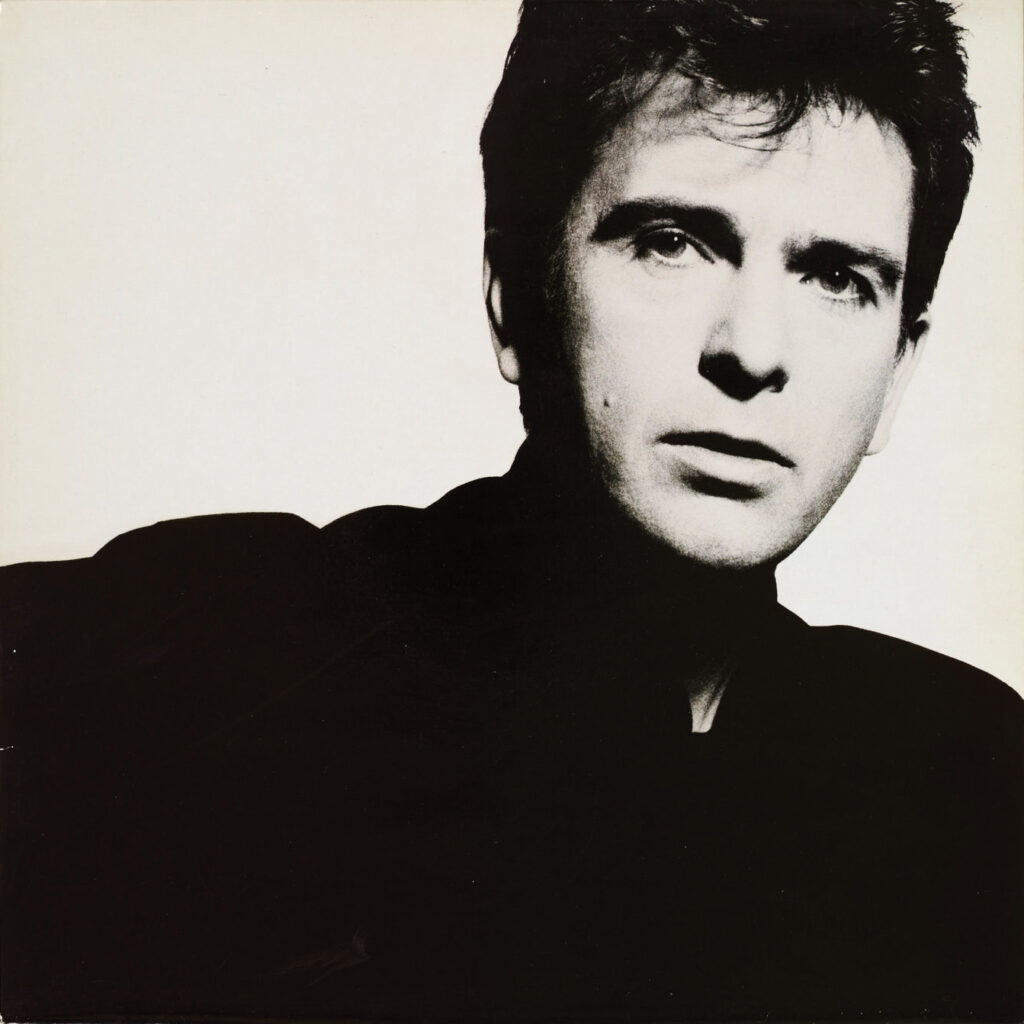

Peter Gabriel

‘so’

(virgin)

“When I think about Trevor Key, I think primarily of his still life work. Ironically, two of his most memorable pieces are works of portraiture – the four beautifully skewed individual studies of New Order (especially Barney) on ‘Low-Life’ and the spirit-capturing shot of Peter Gabriel from his landmark ‘So’ album. There’s a great deal of design in the crop of Gabriel (I don’t need to know whether that was Trevor or Peter Saville’s doing), but the eyes and the gaze and the taught awkwardness of the artist’s pose is something only really seen through a lens. The best designs, those that echo down across the years, aren’t those with built-in longevity, but those which resonate perfectly with their own time and place. In design terms these images, which melded with the music they accompanied, had impact. They were iconic.”

‘So’: Photography by Trevor Key, design by peter saville and brett wickens, Peter saville associates, london, 1986

New Order

‘True Faith’

(Factory)

“The iconic simplicity of the surreal super-real gold leaf with all its connotations of photo/graphically modified/improved nature, prompts the questions, ‘Is it real?’ and ‘Does it matter?’. At first contact we ask if the leaf is modified, a Midas touch in reality, or is it enhanced in a darkroom or by the ones and zeros of technology. I look at this as the simultaneous evolution of New Order’s music and Trevor’s image making moving away from the constricts of the physical into the possibilities of the then less-charted worlds of digital. The essential beauty of photographic images such as this is their flexibility and adaptability across media. It allows us to own the questions… if not the answers.”

Sleeve design by Peter Saville Associates and Trevor Key, 1987

New Order

‘Fine Time’

(Factory)

“Continuing Trevor’s own super-creative fine time in the second half of the 80s is another bang on the bingo image succinctly capturing the pill-powered zeitgeist. On the surface it’s a celebration of a culture coming up, acknowledging no past and believing the future had already arrived. In hindsight, the permutations of the various versions into something more blurred and less focussed accidentally act as a warning to where it could all go Pete Tong. What interests me is that what remains iconic, and maybe visionary, for a generation blossoming in the digital revolution now appears almost perfunctory to a younger generation who are weary of the digital lingua franca and looking beyond technology for inspiration while at the same time unavoidably locked into and unaware of the visual languages Trevor’s work helped shape.”

Cover by Peter Saville Associates and Trevor Key after a painting by Richard Bernstein, 1988

New Order

‘Technique’

(Factory)

“‘Technique’ is one of Trevor Key’s defining moments. It’s not my favourite, but I think I get it, and if I don’t, I like my theory about it anyway. ‘Technique’ completes New Order’s metamorphosis from the rainy-city irony of a band named Joy Division to the outright pop-dance-headonism of pure joy. Gone is the atmospheric monotone neoclassicism of monuments and tortured gargoyles suffocated by bleak grey skies. ‘Technique’ repositions the graveyard statue of those early sleeves on the dancefloor. It is super-nature super-pill pop art. It’s a one-liner of an idea, but what a one-liner.”

Cover by Peter Saville Associates and Trevor Key, 1989

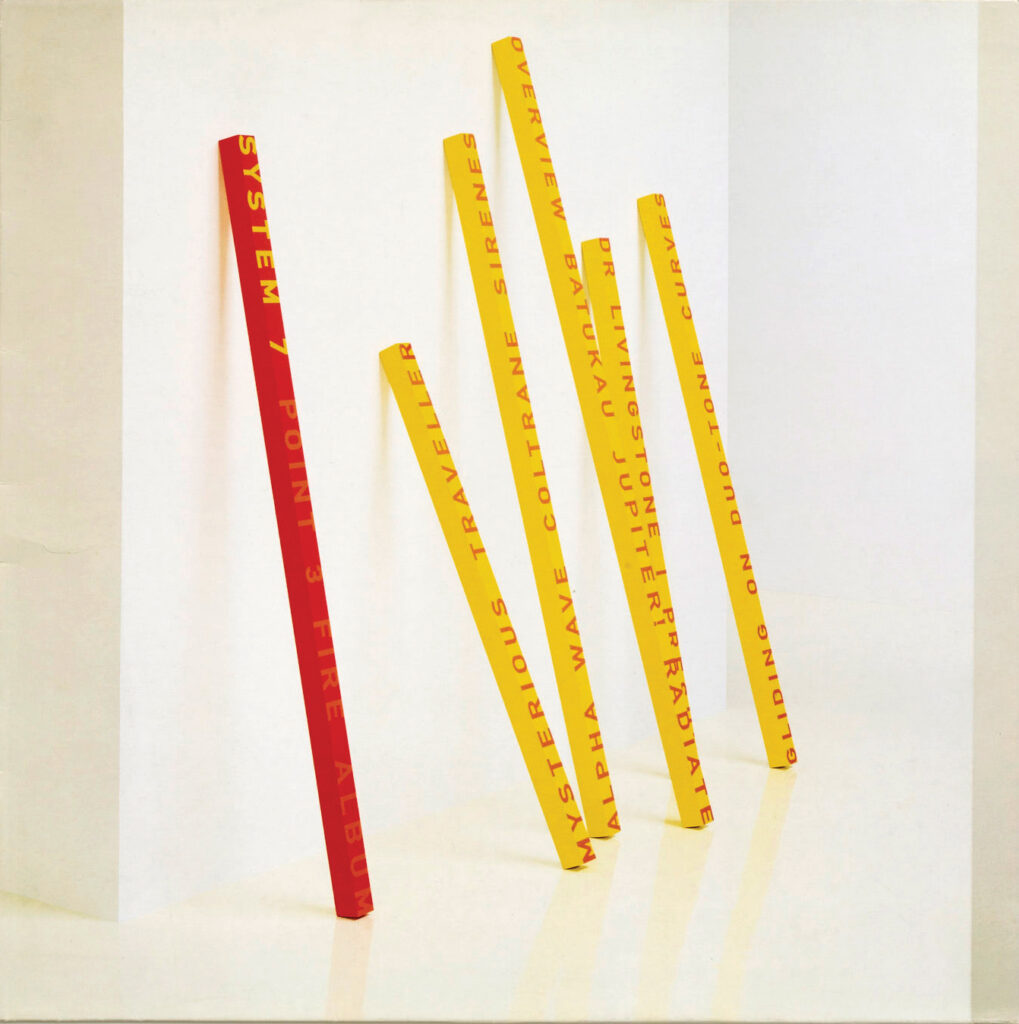

System 7

‘Point 3 – Fire Album’ / ‘Point 3 – Water Album’

“Some photographers shoot from a perspective, both physical and conceptual, that centres the viewer in the image. We, and what we choose to see, complete the equation. What I find intriguing about Trevor’s work is that it places us right there next to, but divorced from, the content as passive bystanders, voyeurs. Take ‘Tubular Bells’, the impact doesn’t come from the elemental natural drama of the crashing waves, nor from any sense of the bell’s ominous presence. It is what it is with or without us. ‘Point 3’, like ‘Tubular Bells’, is an arrangement of emotive elements presented to us almost devoid of personality. The two ‘Point 3’ covers are typographic designs extruded into a physical space so we can assume the photography is something less than art-directed – almost document-ish. But as with the majority of Trevor’s work, the value, to me as a viewer, is an angle, a question, a line of sight and a work of aesthetic beauty.

Design and art direction David James Associates, photography Trevor Key, 1994

Joy Division

‘Atmosphere’

(Factory)

“What are we looking at? Is it Peter Saville’s art direction, Brett Wickens’ design or Trevor Key’s shot? Actually, it is a detail from Jan Van Munster’s 1986 piece ‘Plus En Min’. Or Key’s photograph of it. Or someone’s idea to use it, or how to use it, or frame it. The point is Trevor Key’s most important contribution to the genre is that of a creative collaborator and fellow traveller, an idea maker and image shaker, an editor, a narrator and a curator, not just as a photographer per se.”

CD single insert. ‘Plus en Min’ (detail) by Jan Van Munster, 1986. © 1988 Jan Van Munster/ DACS, Art Direction: Peter Saville. Design: Brett Wickens, Peter Saville Associates. Photography: Trevor Key