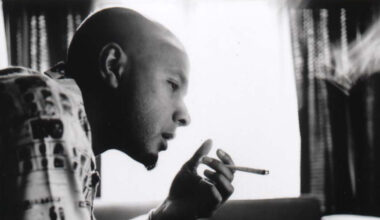

The impact of ‘Selected Ambient Works 85-92’ can’t be overstated. In the three decades since its initial release, it has minted the myth of Aphex Twin and redefined ambient, electronic and dance music. Richard D James, take a bow

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here