Once upon a time, at the dawn of the electronic age, Mark Reeder ran away to join the circus. He never came home again.

Frustrated by the stale new wave scene in late 1970s Manchester, the then 20-year-old Reeder quit his dead-end record store job and his sideline playing bass in The Frantic Elevators, Mick Hucknall’s pre-Simply Red punk band. He then set off for the Bowie-endorsed bohemian enclave of West Berlin in search of rare vinyl, cool people and arty-party adventures. Four decades later, he is still there, a born-again Berliner and founding father of the city’s thriving electronica scene.

Sitting on the terrace of an elegant cafe in Berlin’s perennially shabby chic Kreuzberg district, Reeder can still recall the drizzly night he first arrived in his adopted home city. Hitch-hiking through the depressingly drab East German autobahn corridor that once linked the island citadel to the rest of western Europe, he remembers Berlin’s magical orange glow lighting up the sky ahead. Once he was safely through the grim border checkpoint, he immediately lucked out when friends offered him a palatial free apartment in a grand old building that was scheduled for demolition. It was the start of a love affair with the city that has lasted more than four decades.

Back in 1978, Reeder’s corner of Schöneberg in south-west Berlin was an alluringly grungy pre-gentrification landscape of graffiti-scrawled walls, bombed-out tenement squats, seedy clubs and transvestite bars.

“Berlin resembled nothing like anywhere I’d even been before,” he says. “It was brilliant, it was totally ‘Cabaret’. There were lots of trendy locals and I was thinking to myself, ‘These blokes could all be war criminals dressed up as women, just hanging out every Saturday night’. It would never have occurred to anyone. I could have seen Hermann Göring hanging out there.”

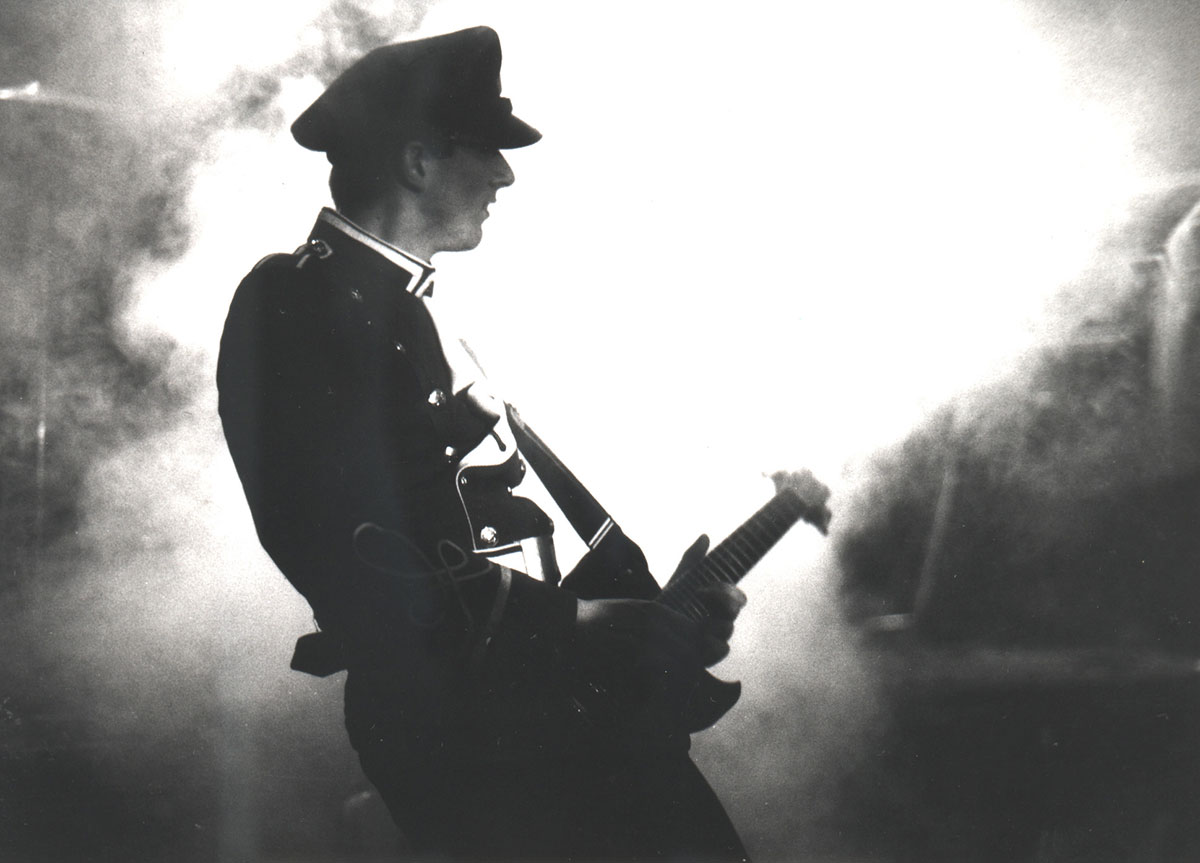

A natural networker with a nose for emerging scenes and an attention-grabbing fetish for military uniforms, Reeder soon began to make his mark on the Berlin underground, just as he had done in post-punk Manchester. Besides mixing with future cult music icons like Gudrun Gut, Blixa Bargeld, Nick Cave and WestBam, he befriended club owners, label bosses, visual artists, fashion designers, writers, filmmakers, junkies, political dissidents and Cold War spies.

“It was like one big band,” recalls Reeder. “We were all doing different things within this little group of people… but it was all interconnected.”

Mark Reeder came to West Berlin just as David Bowie’s epochal Berlin Trilogy helped transform the city into a byword for visionary avant-rock reinvention. Countless more musicians would follow in the Thin White Duke’s footsteps in the 1980s and 1990s, recording and living in the city. Reeder was not exactly a Bowie acolyte, but both these culturally curious English exiles were drawn to Berlin by a shared love of German art rock and electronica.

“It wasn’t the reason, but it was probably a factor,” says Reeder. “I’d been fascinated with krautrock from the early 70s, the kind of records that were impossible to get, you could only read about them in the music press. And then suddenly Kraftwerk became a pop band when they appeared on ‘Top Of The Pops’. They seemed to take something like Tangerine Dream onto a completely different level.”

By fatefully bad timing, Bowie had left Berlin just weeks before Reeder showed up, but his spirit still hovered over the city’s artistic community.

“There was a certain novelty when he was living here, but they just let him get on with his life,” notes Reeder. “Blixa Bargeld actually lived quite near Bowie, he’d see him buying his milk in the supermarket, but he’d never go up to him and tap him on the shoulder. They don’t do that here. Never in a million years will they bother you.”

Reeder may have just missed Bowie, but he did have a sneaky look around Bowie’s vacated flat at 155 Hauptstraße in Schöneberg. His accomplice was a rocker friend, New York punk guitarist Avis Davis, who was temporarily living in Iggy Pop’s apartment in the same building.

“Iggy’s flat was a right shambles,” laughs Reeder. “It was this shabby one-room apartment. There was a sofa, a crappy wardrobe, a million T-shirts, hundreds of carrot juice bottles in the kitchen…”

Bowie’s apartment was bigger, but disappointingly low on rock-god glamour.

“I expected to see this fantastic, palatial, super-designer place,” he continues. “And it wasn’t. It was just normal. He had this horrible flowery wallpaper and an old carpet. It was dead down to earth, like a 1960s council house. Only the kitchen had been a bit done up. I can’t imagine he’d have chosen that wallpaper, I think it was just what he’d moved in to. He didn’t give a shit, really. I think he just wanted to blend into the background and chill out.”

Like most fringe music communities, West Berlin’s post-punk underground was essentially a village of like-minded souls. It revolved around a handful of no-frills clubs and venues, notably the landmark punk bunker SO36 on Oranienstraße in Kreuzberg, which is still going strong today. In the early 1980s, the city’s most fabled late-night drinking den was Risiko, huddled beneath two rusty railway bridges on Yorckstraße in Schöneberg. Blixa Bargeld worked behind the bar, while regular clients included Nick Cave, Wim Wenders and Christiane Felscherinow, the former teenage junkie whose life inspired the seminal Bowie-endorsed Berlin drug movie ‘Christiane F’.

Also crucial to Berlin’s emerging alternative scene was a rash of hastily formed independent labels, some springing up from boutiques that sold both music and clothes. Zensor on Belziger Straße was the place to find new wave imports from Britain and America, while the cavernous Eisengrau on Golzstraße was a DIY fashion emporium run by Gudrun Gut and Bettina Köster. Gut and Köster co-founded the all-female avant-punk outfit Mania D with their friend Beate Bartel in 1979.

“Gudrun couldn’t drum, Bettina couldn’t play saxophone, Beate couldn’t play bass,” says Reeder. “But they all did whatever it was they did to make their own thing. I was awed by them. It was such a refreshing approach. They didn’t adhere to any of the rules of rock ‘n’ roll.”

Blixa Bargeld also had a brief spell working at Eisengrau. When he formed metal-bashing noise-rock extremists Einstürzende Neubauten in 1980, Gudrun Gut and Beate Bartel joined the band’s nascent line-up. But the two women soon left to further explore their own musical ideas, reuniting with Bettina Köster in the groundbreaking synth-punk trio Malaria!, who recruited Reeder to work as their live sound engineer and sometime manager.

Malaria! did not last long, but they played a lead role in the development of the Neue Deutsche Welle (German New Wave) and inspired more successful spin-off bands like Liaisons Dangereuses, which Bartel joined in 1981. Gut went on to become the queen mother of Berlin’s arty electronica scene – and she remains so today. Reeder argues that it was Gut’s restless creative energy that fuelled much of the city’s post-punk music scene.

“Let’s face it, without Gudrun there would have been no Berlin scene,” he says. “She was it. She created it, basically. She wanted to be in a new band every week. She provided us with the balls to have a go. Then people started to jump on that, people who were not necessarily musicians were suddenly wanting to express themselves musically.”

Like most of the early 1980s West Berlin underground, Reeder scraped a living doing multiple jobs – musician, producer, band manager, TV presenter and occasional actor. Drawing on his Manchester contacts, he also served as the German ambassador for Factory Records, promoting the label and hustling for gigs.

“It was just basically me promoting Joy Division, or trying to at least,” says Reeder. “But no one was interested, no one fucking gave a shit. It was miserable Manchester music.”

Reeder did help to secure Joy Division their only ever Berlin show though, at the Kant Kino cinema close to Zoo Station in January 1980.

“It was a complete and utter disaster,” he says. “Only around 50 people turned up instead of the expected 200, the sound was terrible, and Bernard Sumner antagonised the tetchy crowd by shouting, ‘Speak fucking English, you German bastards!’. That was it, the gig was virtually over. The already fragile atmosphere, which had just about held together, was destroyed instantly. But the band thought it was a great gig. They were so used to playing such crap gigs, they thought it was just like all the others.”

Reeder also formed his own Berlin new wave band, Die Unbekannten (The Unknown), almost by mistake. In June 1981, a promoter friend needed additional performers to pad out the bill for a mini-festival at SO36, a mock celebration of German reunification that proved unexpectedly prophetic. Reeder hastily recruited fellow British ex-pat singer Alistair Gray and future Bad Seeds drummer Thomas Wylder to knock some songs together.

“We got completely pissed writing the lyrics,” he says. “Waiting for a soundcheck down the street, we were drinking beers and schnapps and shit. Then we took these speed tablets that the long-distance lorry drivers used. We were chucking those down and getting off our faces… what could go wrong?”

Unsurprisingly, the show was a shambolic, off-key disaster. Even so, the founder of Berlin indie label Monogram, Elisabeth Recker, was impressed enough by the accidentally avant-garde racket to release two EPs by Die Unbekannten. Monogram also became a launchpad for other Berlin post-punk acts, including Mania D and Einstürzende Neubauten. In 1984, Reeder and Gray rebranded the band as synthpop trio Shark Vegas, who released a single on Factory and toured with New Order.

With its libertine ambience and round-the-clock licensing laws, Berlin has always been a boozy, druggy city. Alcohol was “dirt cheap”, Reeder confirms, especially the duty-free brands smuggled back from hard currency shops in East Berlin. But the hedonistic mood took a darker turn after the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, when cut-price heroin began to flood the city.

“They were freighting in fucking thousands of tons of heroin and marijuana with Soviet military transport planes,” he recalls. “They brought the stuff into East Berlin, then took it across the border. They didn’t want to sell it in the East. They wanted hard cash – dollars and pounds and Deutschmarks – and they also wanted to show the eastern kids how decadent the western kids were. All the harder drugs, like speed and LSD, that all came from the East too.”

Meanwhile, the Cold War was still in full swing during Reeder’s first decade in the city, fuelling a mood of political paranoia that even seeped into the music scene. Within weeks of arriving, he began making forays behind the Berlin Wall. In 1982, he helped organise the first-ever concert by a western punk band in East Berlin, taking Düsseldorf rockers Die Toten Hosen over to play an illegal gig which they pretended was a church prayer meeting. The band had to borrow instruments from a group of local musicians who later went on form industrial metal superstars Rammstein.

Curious to see more of the Eastern Bloc, Reeder travelled further afield, to Prague, Budapest and beyond. He soon fell in with a group of Czech artists and activists affiliated to the dissident organisation Charter 77. He risked arrest by trading underground magazines, smuggling in western music cassettes, and playing secret gigs disguised as wedding receptions.

“After I’d been to East Berlin, I started wondering what the rest of it looked like over the border,” he says. “Czechoslovakia was the nearest and it was this beautiful, magical place. And it was like the beer was free! Your money went for miles. It was great. I went as often as possible.”

Only years later, after the fall of communism, did Reeder learn that he was being monitored by the Stasi, East Germany’s notorious secret police, almost from his first foray behind the Wall. Even some of his East Berlin punk friends had been pressured to spy on him by the authorities.

“The one who was the biggest Stasi informer of all was the person that we least suspected,” he notes. “It was a girl and she was a sort of Mata Hari. She knew everything and everybody.”

Like thousands of West Berliners who forged friendships in the communist East, Reeder became the subject of a substantial Stasi file. But while most current German citizens have been granted access to their Stasi notes, he is only permitted to view a fraction of his file, which is still closely guarded by the government 30 years after the country’s reunification. Too many spies, too many dark secrets.

“It’s a long story,” he sighs. “At one point, the Czech secret service came to West Berlin and infiltrated the Czech dissident movement, using my flat as a base… I got dragged into that in the late 80s and early 90s.”

As the 1980s drew to a close, Reeder sensed a sea change approaching, as acid house, techno and ecstasy began to sweep West Berlin. He found himself on the fringes of another emerging underground scene, this time emanating from the fabled UFO, an illegal rave venue crammed into a basement on Köpenicker Straße in Kreuzberg. The UFO would later spawn the revered techno club and label Tresor, now a long-running Berlin institution.

In July 1989, just months before the Wall fell, Reeder attended a street carnival with a fuzzy political message on West Berlin’s main shopping boulevard, the Kurfürstendamm. The weather was wet and the response was poor, with just 150 people in attendance. But the first Love Parade was a signpost to the future, when 1990s Berlin would reinvent itself as the techno capital of the universe, drawing million-strong crowds of ravers from across the globe.

As the Wall fell and the 1990s dawned, Reeder embarked on a new career as a club DJ, remixer and dance music mogul. He launched the trance label MFS and steered East Berlin DJ Paul van Dyk to superstar success. Post-punk Berlin was dead, but a gleaming new electropolis was being built on its ruins. And once again, with his uncanny nose for a great party, Mark Reeder was at the heart of the action.

“At the early Love Parades, everybody was in love together, everybody was on the same drug, everybody was dancing together,” he says with a wistful smile. “I remember this old bloke stopping and looking at us as we went past. He was maybe 80 years old and he’d seen quite a lot of changes in Germany, the communist takeover, the Wall going up… all things like that. He looked as us with an expression of total intolerance. And I was like, ‘Yes! That’s it!’. I saw the expression on his face and I knew that we had won.”